This Key Event Relationship is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-SA license. This license allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms.

Relationship: 3473

Title

Plasma estradiol/progesterone ratio, increase leads to Persistent vaginal cornification

Upstream event

Downstream event

Key Event Relationship Overview

AOPs Referencing Relationship

| AOP Name | Adjacency | Weight of Evidence | Quantitative Understanding | Point of Contact | Author Status | OECD Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased, GnRH pulsatility/release leading to estradiol availability, increased via impaired ovulation | adjacent | Martina Panzarea (send email) | Under development: Not open for comment. Do not cite |

Taxonomic Applicability

Sex Applicability

Life Stage Applicability

Key Event Relationship Description

Evidence Collection Strategy

Evidence Supporting this KER

Biological Plausibility

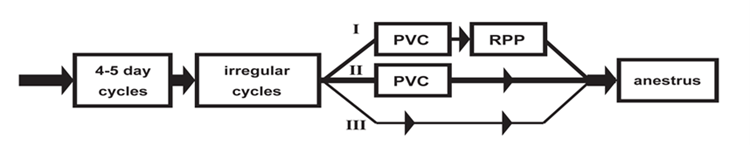

The biological plausibility of the key event relationship is supported by aging rodent females. Reproductive senescence in rodents results from initial centrally mediated changes with alterations in hypothalamic function (Gore, 2000; Kermath, 2012). Female rats and mice proceed through sequential reproductive stages. Female rats undergo a transition from regular estrous cycles to irregular cycles (up to the age of 3- to 7-month-old), followed by persistent estrus (characterized by PVC), then repetitive pseudopregnancy (also called persistent diestrus) and finally anestrus (Finch, 2014; Shirai, 2015). However, there are species and strain differences in the pattern of changes and timing in the onset of reproductive senescence (Vidal, 2017). The tree different pathways of reproductive senescence are represented in Fig. 17 (Finch, 2014) and the pattern and the age at cycle cessation in different strains of rats and mice are available in Table 5 (Nelson, 1982). PE begins to be observed in Sprague-Dawley rats by 6 to 7 months of age (Vidal, 2017) or even earlier (Elridge, 1999). In contrast, Han Wistar rats are reported to have cycle irregularities after 6 months of age and move mainly into persistent diestrus (Mitchard and Klein 2016).

Figure 17. Alternate trajectories of rodent reproductive senescence from (Finch, 2014)

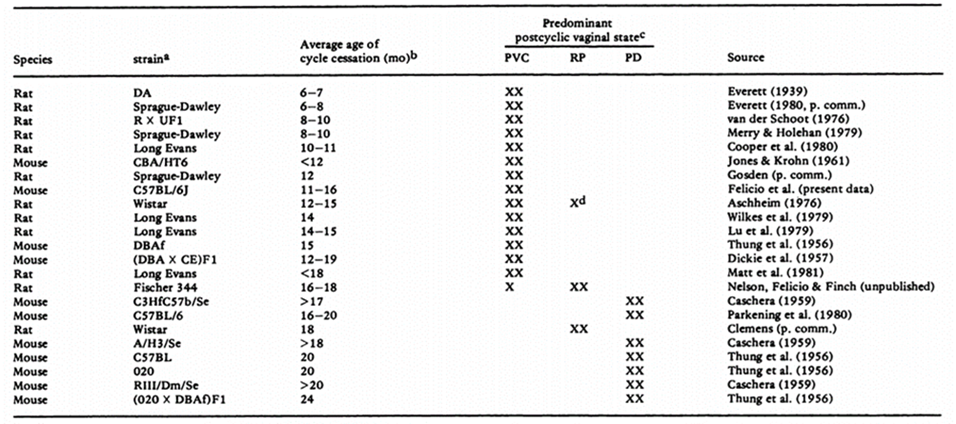

Table 5. Incidence and vaginal cytological status of prolonged cycles in different strains of mouse and rat ranked by age (Nelson, 1982)

In aged rodents showing persistent vaginal cornification, the hormonal profile is characterized by sustained E2 and low P (Finch 2014). This hormonal change is explained by the histopathology of ovary showing numerous follicular cysts (producing estradiol) and lack of corpora lutea (producing progesterone).

The link between increased E2/P4 ratio and PVC has been demonstrated in different strains of both species. In a comparative study between Donryu and Fischer-344 rats, Nagaoka et al., sequentially followed estrous cycles by vaginal smear as well as E2 and P plasma levels, up to the age of 15 months. The E2/P4 ratio was higher in Donryu rats than in F-344 rats from 8 month of age and was about 7 times higher (p < 0.01) at 12-month. In Donryu rats persistent estrous (measured as PVC) appeared in 17% of the 5-month animals, the prevalence increased with age (90% of the 10-month animals while almost all F-344 rats showed a normal estrous cycle up to 8 months, and only a few cases showed persistent estrous thereafter). The authors concluded that the sustained increased E2/P4 ratio observed in Donryu rats may explained the high spontaneous occurrence of uterine endometrial adenocarcinoma in Donryu rats compared to F-344 rats (Nagaoka, 1994). The link between increased E2/P4 and PVC was also showed in aging Long Evans rats (Lu, 1979 and C578L/6J mice (Nelson, 1981) in which increased E2/P4 ratio was observed in PVC rats and mice compared to younger cycling animals.

Empirical Evidence

Atrazine

Several studies in Sprague-Dawley (SD) female rats have shown that prolonged administration of atrazine by diet induced earlier increase of the number of animals displaying PVC. However, only one publication reports the investigation of both the KE upstream and KE downstream events SD rats and Fischer-344 rats.

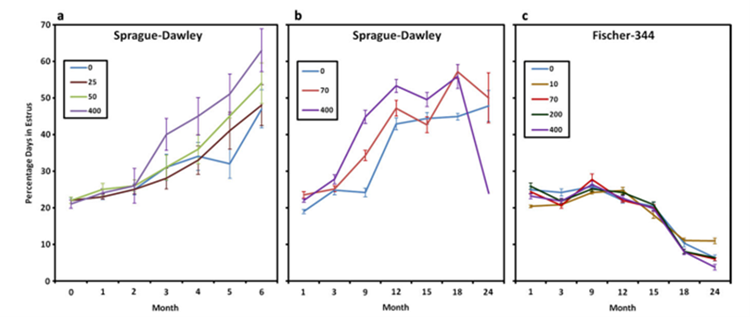

In a 6-month repeated dose toxicity studies (0, 25, 50 or 400 ppm), the number of animals with persistent estrous at 400 ppm was increased compared to controls from three months onwards (20/90 vs 10/90 at 3 months; 50/90 vs 26/90 at 6 months). A significant increase in percent of total days with estrous was noted in the 400ppm group after three months of treatment (Eldridge, 1999, Simpkins 2011, see also Fig. 18). In a 24-month chronic toxicity studies with interims kills in SD rats (0, 70, 400 ppm with interim kills every 3 months) and Fischer-344 rats (0, 10, 70, 200 or 400 ppm) a dose-dependent increased in the percent days in estrous stage was noted from the 70 ppm SD group after nine months of treatment reaching statistically significance only at time point 9-month). There was no effect of 400ppm atrazine on cyclicity in female Fischer-344 rats. Plasma E2 concentrations were significantly increased from 70 ppm onwards at 3 months in SD rats but not in Fischer rats. No other significant effects on E2 and progesterone were seen in both species (Wetzel, 1994; US EPA 2000; USEPA, 2018). However, when calculating the E2/P4 ratio from the data reported in Wetzel, 1994, a dose-dependent increased of E2/P4 ratio is noted at 3- and 9-month time points in SD female rats while no effect was observed in female Fischer-344 rats (Table 6).

Figure 18. (b) Dose- and time-dependent effect of 0, 25, 50, or 400 ppm atrazine administered in the diet on the percent days in estrous in female SD rat (b) Comparison of the dose- and the time-dependent effects of atrazine administered at dietary concentrations of 0, 70, or 400 ppm on the percent days in estrous in female SD rats (c) Atrazine administered at dietary concentrations of 70 or 400 ppm had no effect on the percent days in estrous in female Fischer 344 rats (Simpkins, 2011)

|

|

E2/P4 ratio |

||||

|

Time (month) |

SD |

Fischer 344 |

|||

|

|

0 |

70 |

400 |

0 |

400 |

|

1 |

0.46 |

0.19 |

0.57 |

0.44 |

0.30 |

|

3 |

0.22 |

0.68 |

1.27 |

0.83 |

1.24 |

|

9 |

1.97 |

2.52 |

4.22 |

0.94 |

0.96 |

|

12 |

3.28 |

1.81 |

3.66 |

0.33 |

0.17 |

|

15 |

1.22 |

3.85 |

0.77 |

0.20 |

0.15 |

|

18 |

0.19 |

1.38 |

1.27 |

0.10 |

0.20 |

|

24 |

0.75 |

0.26 |

0.23 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

Table 6. E2/P4 ratio calculated from Wetzel, 1994 data

These different studies are thoroughly assessed in different available documents of US EPA evaluation (Issues Pertaining to Atrazine Cancer Risk Assessment, US EPA 2000 https://archive.epa.gov/scipoly/sap/meetings/web/html/062700_mtg.html,)

GnRH antagonist Cetrorelix

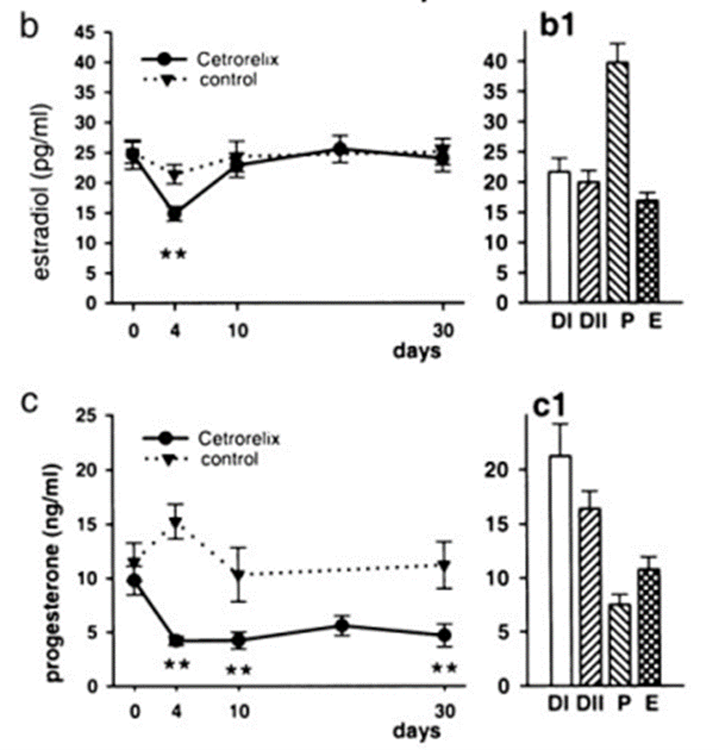

After 30-day intramuscularly treatment of Cetrorelix (depot formulation corresponding to 20–24 µg/kg per day) in SD females (proestrous at day 0) Estradiol levels in the group given Cetrorelix were significantly reduced (P < 0.01) by 30% on day 4 of the experiment but returned to control values after day 10. While progesterone levels decreased in the treated rats by more than 50% on day 4 and remained at this significantly lower level (P < 0.01) through the entire experiment, resulting in an increased E2/P4 ratio (Fig. 21).

The treatment induced prolonged (4–6 days) diestrous phase followed from day 6 by persistent estrous smears in most rats (75.5% of the smears examined between days 6 and 30 showed estrous) (Horvath, 2004, see also Fig 19).

Figure 19. Effect of Cetrorelix pamoate on serum E2 and P4 in female rats during the treatment (b1 and c1: serum E2 and P in control female rats at different stages of estrous cycle (Horvath, 2004)

Dose and temporal concordance

- Atrazine: The dose and temporal concordance is well demonstrated in the only study available investigating both the up and downstream KEs. However only two dose levels were tested (Table 7).

- Cetrorelix: only one dose was tested and the experiment lasted only 30 days, which significantly limit the evaluation of the dose and temporal concordance (Table 7).

Table 7. Dose and temporal concordance studies

|

Species, life-stage, sex tested |

Stressor(s) |

Upstream Effect: plasma E2/P4 ratio (Y/N) |

Downstream Effect: on increased E2 availability PVC (Y/N) |

Effect on increased plasma E2/P4 ratio (descriptive) |

Effect on increased E2 availability in uterus (descriptive) |

Citation |

|

In vivo |

||||||

|

SD female rats 24 months diet 0, 70 or 400 ppm (0, 4.23 or 26.23 mg/kg bw per day) |

Atrazine |

Y |

Y |

E2/P4 ratio: dose response increased from 70 ppm at Month-3 and Month-9. |

Month-9: statistically significant ↑ % total days in Estrous 34.3%, 44.8% at 70 and 400 ppm respectively vs 24.2% in controls |

Wetzel 1994 Eldridge 1994 Also reported in US EPA 2000 and 2018 |

|

SD female rats 0, 30-day (IM depot formulation) (corresponding to 20–24 µg/kg per day) |

Cetrorelix |

Y |

Y |

E2: 30% ↓ on D4 Then returns to control values P: ↓50% * of D4 remained low until the end of the experiment. |

Persistent Diestrous up to D6 Persistent Estrous from D6 to D20 (75.5% of vaginal smear smears estrous stage) |

Horvath, 2004 |

Dose and temporal concordance

See Annex B.3.

Uncertainties and Inconsistencies

- Only two stressors have been investigated. The dose and temporal concordance should be further substantiated with other stressors.

- E2 bioavailability in uterus was not measure directly in any of the studies reported: the empirical evidence of the KER relies on the indirect measurement of the downstream KE (i.e., the surrogate event PVC). It should be highlighted that Atrazine was negative in a uterotrophic bioassay performed in ovariectomized SD females which is not considered as an uncertainty but rather supports that atrazine does not exhibit a direct estrogenic activity. An intact HPG axis is necessary which is not the case in ovariectomized females.

- Sex hormone measurements are rarely carried out in female rodents' studies, which limits the investigation of the empirical evidence of this KER.

- Characteristics of reproductive aging in the female rats varies among strains (Chapin, 1996; Finch, 2014). This could explain the discrepancies of the results observed between SD and Fischer female rats exposed to atrazine.

- The internal quality of the primary research study used to substantiate the empirical evidence has not been evaluated (recommendation).

Known modulating factors

Quantitative Understanding of the Linkage

Response-response Relationship

Time-scale

Known Feedforward/Feedback loops influencing this KER

Domain of Applicability

References

Eldridge JC, Tennant MK, Wetzel LT, Breckenridge CB and Stevens JT, 1994. Factors affecting mammary tumor incidence in chlorotriazine-treated female rats: hormonal properties, dosage, and animal strain. Environ Health Perspect, 102 Suppl 11:29-36. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s1129

Eldridge JC, Wetzel LT and Tyrey L, 1999. Estrous cycle patterns of Sprague-Dawley rats during acute and chronic atrazine administration. Reprod Toxicol, 13:491-499. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(99)00056-8

Finch CE, 2014. The menopause and aging, a comparative perspective. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 142:132-141. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.03.010

Gore AC, Oung T, Yung S, Flagg RA and Woller MJ, 2000. Neuroendocrine mechanisms for reproductive senescence in the female rat: gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrine, 13:315-323. doi: 10.1385/endo:13:3:315

Horvath JE, Toller GL, Schally AV, Bajo AM and Groot K, 2004. Effect of long-term treatment with low doses of the LHRH antagonist Cetrorelix on pituitary receptors for LHRH and gonadal axis in male and female rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 101:4996-5001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400605101

Kermath BA and Gore AC, 2012. Neuroendocrine control of the transition to reproductive senescence: lessons learned from the female rodent model. Neuroendocrinology, 96:1-12. doi: 10.1159/000335994

Mitchard TL and Klein S, 2016. Reproductive senescence, fertility and reproductive tumour profile in ageing female Han Wistar rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol, 68:143-147. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2015.11.006

Nagaoka T, Takeuchi M, Onodera H, Matsushima Y, Ando-Lu J and Maekawa A, 1994. Sequential observation of spontaneous endometrial adenocarcinoma development in Donryu rats. Toxicol Pathol, 22:261-269. doi: 10.1177/019262339402200304

Shirai N, Houle C and Mirsky ML, 2015. Using Histopathologic Evidence to Differentiate Reproductive Senescence from Xenobiotic Effects in Middle-aged Female Sprague-Dawley Rats. Toxicol Pathol, 43:1158-1161. doi: 10.1177/0192623315595137

Simpkins JW, Swenberg JA, Weiss N, Brusick D, Eldridge JC, Stevens JT, Handa RJ, Hovey RC, Plant TM, Pastoor TP and Breckenridge CB, 2011. Atrazine and breast cancer: a framework assessment of the toxicological and epidemiological evidence. Toxicol Sci, 123:441-459. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr176

USEPA, online. Issues Pertaining to Atrazine Cancer Risk Assessment. Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/scipoly/sap/meetings/web/html/062700_mtg.html

USEPA, online. Atrazine. Draft human health risk assessment for registration review. In atrazine registration review. . Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-07-26/pdf/2018-15998.pdf

Vidal JD, 2017. The Impact of Age on the Female Reproductive System. Toxicol Pathol, 45:206-215. doi: 10.1177/0192623316673754

Wetzel LT, Luempert LG, 3rd, Breckenridge CB, Tisdel MO, Stevens JT, Thakur AK, Extrom PJ and Eldridge JC, 1994. Chronic effects of atrazine on estrus and mammary tumor formation in female Sprague-Dawley and Fischer 344 rats. J Toxicol Environ Health, 43:169-182. doi: 10.1080/15287399409531913