This Event is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-SA license. This license allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms.

Event: 2362

Key Event Title

Redox cycling of a chemical by mitochondria

Short name

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Molecular |

Cell term

| Cell term |

|---|

| cell |

Organ term

| Organ term |

|---|

| organ |

Key Event Components

Key Event Overview

AOPs Including This Key Event

| AOP Name | Role of event in AOP | Point of Contact | Author Status | OECD Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redox cycling and parkinsonian motor deficits | MolecularInitiatingEvent | Stefan Schildknecht (send email) | Under development: Not open for comment. Do not cite |

Taxonomic Applicability

Life Stages

| Life stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| All life stages | High |

Sex Applicability

| Term | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

| Female | High |

Key Event Description

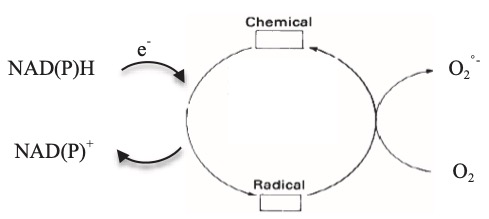

Redox cycling is a process of alternate reduction and reoxidation steps. Redox cyclers are compounds capable of undergoing repeated cycles of reduction and oxidation, driving the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide (O₂•⁻). (Drechsel et al. 2009; Hassan et al. 1984; Bus et al. 1974) This process begins when a redox cycler accepts a single electron from a biological reductant—often catalyzed by flavoprotein oxidoreductases like NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, nitric oxide synthase, or mitochondrial enzymes such as NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase and components of the respiratory chain, particularly complex I (Shimada et al. 1998; Thor et al. 1982). The electron transfer to the redox cycler forms a transient radical intermediate. This radical is highly reactive and quickly donates its extra electron to molecular oxygen, forming superoxide and regenerating the parent compound. Because the parent redox cycler is restored, the cycle can repeat, continuously producing ROS as long as both reductant and oxygen are available (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the mechanism of chemicals redox cycling. (Adapted by permission from Macmilllan Publishers Ltd, Cohen and Doherty, 1987, copyright (1987))

The efficiency and direction of redox cycling depend on the redox potential of the involved species. Redox cyclers typically have highly negative reduction potentials, enabling them to accept electrons from specific cellular reductants and to rapidly reduce oxygen (standard redox potential for O₂/O₂•⁻ ≈ –0.16 V at pH 7) (Drechsel et al. 2009a; Hassan et al. 1984; Bus et al. 1974; Drechsel et al. 2009b; Bus et al. 1984; Sawyer et al. 1981). In animal systems, redox cyclers can drive oxidative stress (Fussell et al. 2011), contributing to toxicological outcomes such as neurodegeneration. Mitochondrial complex I is especially efficient at reducing redox cyclers due to its highly negative redox centers, which matches the redox requirements of these compounds better than other mitochondrial sites like complex III (Castello et al. 2007; Cocheme et al. 2008; Drechsel et al. 2009b)

Redox cyclers are a class of exogenous or endogenous compounds that undergo cyclic one-electron reductions and subsequent reoxidations, facilitating the continuous transfer of electrons from reducing equivalents to molecular oxygen, thereby enhancing the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Within the mitochondrial respiratory chain, particularly at complexes I and III, redox cyclers can substantially amplify ROS production through their molecular interactions with redox-active centers, bypassing normal electron flow and promoting aberrant oxygen reduction. This mechanistic interaction contributes to mitochondrial oxidative stress and cellular injury and is a key feature in the pharmacological activity or toxicity of various quinone-based compounds, including certain chemotherapeutics and environmental toxins.

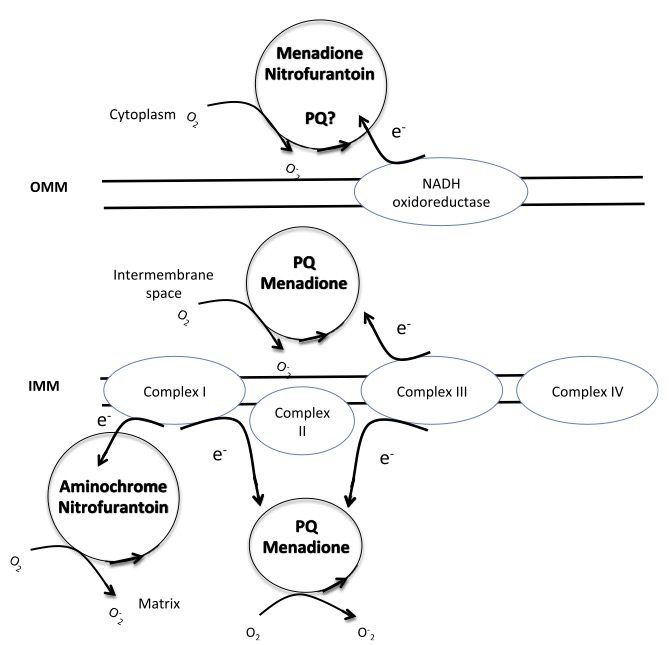

Fig.2. Chemical redox cycling in mitochondria. Complex I and Complex III start PQ redox cycle in bovine heart and brain mitochondria respectively, while the involvement of outer mitochondrial membrane NADH-oxidoreductase is controversial. OMM: outer mitochondrial membrane, IMM: inner mitochondrial membrane.

Complex I and Redox Cyclers. Complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) contains multiple redox centers, including flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and a series of iron–sulfur (Fe–S) clusters, which facilitate electron transfer from NADH to ubiquinone (Verkhovskaya et al. 2008; Dutton et al. 1998; Medvedev et al. 2010; Ohnishi et al. 1998). Redox-active compounds, particularly quinones such as paraquat and menadione, interact with complex I by accepting electrons from the reduced FMN or Fe–S centers. Once reduced, these compounds can rapidly donate their acquired electrons to molecular oxygen, generating superoxide (O₂•⁻) in a catalytic cycle independent of normal ETC function. This redox cycling occurs predominantly at the FMN site of complex I, which is accessible to hydrophilic redox cyclers (Cocheme et al. 2009). These molecules effectively compete with endogenous electron acceptors for reduced FMN, diverting electrons toward oxygen rather than to ubiquinone. As a result, the presence of redox cyclers increases the rate of one-electron oxygen reduction, resulting in elevated superoxide formation. Importantly, this mechanism does not require electron flow through the entire ETC, and ROS production can proceed even when downstream complexes are inhibited or collapsed by membrane depolarization (Cocheme et al. 2008; Cocheme et al. 2009).

Complex III and Redox Cyclers. Complex III (ubiquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase) is another major site of ROS production under the influence of redox-active molecules. The Q-cycle mechanism of complex III involves the oxidation of ubiquinol at the outer Qo site and the reduction of ubiquinone at the inner Qi site. During this process, a semiquinone intermediate is formed at the Qo site, which can react with oxygen to produce superoxide (Zhang et al. 2007). Lipophilic redox cyclers, such as some synthetic naphthoquinones and anthraquinones, can penetrate the inner mitochondrial membrane and localize at or near the ubiquinone-binding sites. These molecules can either act as artificial substrates for the Qo site or influence the redox state of ubiquinone intermediates by enhancing semiquinone stabilization (Castello et al. 2007). This interaction increases the lifetime and reactivity of the semiquinone intermediate, facilitating superoxide formation. Moreover, redox cyclers may promote the formation of aberrant redox couples that participate in futile cycling, further driving ROS generation. In addition to directly interacting with the redox centers of complex III, redox cyclers may alter the intramembrane redox balance, leading to an over-reduction of the ubiquinone pool. This condition is conducive to reverse electron transport (RET) at complex I, creating a feed-forward loop of ROS amplification involving both complexes.

How It Is Measured or Detected

Redox cycler detection by EPR:

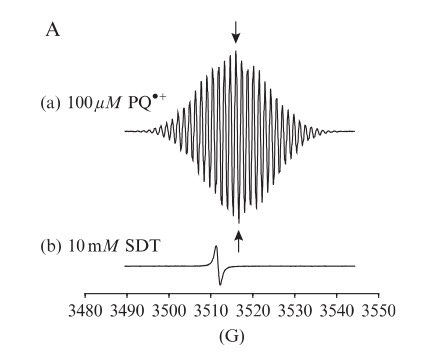

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy provides a highly sensitive and specific method for detecting paramagnetic intermediates such as semiquinone radicals, thereby offering a direct probe into redox cycling events at the mitochondrial level. Through the application of EPR spectroscopy under controlled oxygen and substrate conditions, it is possible to monitor the formation and stability of these intermediates in situ. EPR spectra typically reveal distinct signal patterns corresponding to different redox states and radical species, allowing for the differentiation between catalytic redox cycling and simple redox reactions. Spin trapping agents may be employed to enhance detection of transient radical species, and temperature control enables the stabilization of labile intermediates.

In the presence of molecular oxygen, the interaction of a redox cycler with O2 leads to the formation of superoxide (·O2-), and concomitant regeneration of the redox cycler. Measurements have therefore be conducted under O2-free conditions. The redox cycler is characterized by the delocalization of the unpaired electron across the conjugated ring system, allowing detection of a distinct EPR spectrum. Reduction can be achieved with sodium dithionite (Drechsel et al. 2009a; Cocheme et al. 2009; Minakata et al. 1988)

Redox cycler detection by spectrophotometry

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy provides a highly sensitive and specific method for detecting paramagnetic intermediates such as semiquinone radicals, thereby offering a direct probe into redox cycling events at the mitochondrial level (Cocheme et al. 2009). Through the application of EPR spectroscopy under controlled oxygen and substrate conditions, it is possible to monitor the formation and stability of these intermediates in situ. EPR spectra typically reveal distinct signal patterns corresponding to different redox states and radical species, allowing for the differentiation between catalytic redox cycling and simple redox reactions. Spin trapping agents may be employed to enhance detection of transient radical species, and temperature control enables the stabilization of labile intermediates.

In the presence of molecular oxygen, the interaction of a redox cycler with O2 leads to the formation of superoxide (·O2-), and concomitant regeneration of the redox cycler (Hassan et al. 1984; Bus et al. 1974; Bus et al. 1984; Drechsel et al. 2009a). Measurements have therefore be conducted under O2-free conditions. The redox cycler is characterized by the delocalization of the unpaired electron across the conjugated ring system, allowing detection of a distinct EPR spectrum. Reduction can be achieved with sodium dithionite (Drechsel et al. 2009a; Cocheme et al. 2009; Minakata et al. 1988).

An example of an EPR spectrum of the PQ•+ radical is shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3. Detection and quantification of the PQþ radical by EPR spectroscopy. (A) Typical EPR spectrum of the PQþ radical (100 mM; trace (a)) generated in vitro by reduction of PQ2þ with a twofold excess of sodium dithionite. EPR signal of the SO 2 radical present in the dithionite solution (10 mM; trace (b)). Modified after Cocheme and Murphy, 2009 Methods in Enzymology, Copyright (2009)) Cocheme and Murphy, 2009

Redox cycler detection by spectrophotometry

The detection of radical formation within redox cyclers by spectrophotometry relies on the ability to monitor changes in absorbance associated with the generation and stabilization of specific radical intermediates, most commonly semiquinone radicals. These radicals are formed during one-electron redox processes when the redox-active compound cycles between fully oxidized and fully reduced states, and they often exhibit characteristic UV-visible absorption spectra that can be exploited for detection and quantification.

Redox cyclers such as quinones (e.g., menadione, duroquinone) or nitroaromatic compounds can form semiquinone radicals upon single-electron reduction, typically mediated by mitochondrial or cytosolic reductases. The semiquinone radical is a transient species that displays distinct absorbance bands, often in the visible region (e.g., 400–600 nm), depending on the chemical structure of the redox cycler. For instance, the semiquinone form of menadione exhibits an absorption maximum around 430 nm. By recording the absorption spectrum during redox cycling under anaerobic or low-oxygen conditions (to prevent rapid reoxidation), the formation of the radical intermediate can be detected in real time.

The paraquat (PQ•+) radical has an absorption spectrum with a maximum at 603 nm (e = 13.600 M-1cm-1). Experiments can be conducted with isolated mitochondria in an O2-free system (samples purged with nitrogen or argon). An increase in the absorption at 603 nm indicates an elevated formation of PQ•+. Mitochondrial preparations exhibit absorptions in the range of 500 nm – 700 nm. To confirm that the absorbance at 603 nm is based on PQ•+ signal, the samples are scanned from 500-700 nm under anaerobic conditions and subsequently under aerobic conditions. The presence of O2 converts PQ•+ back to PQ2+. The difference spectrum eliminates the influence of mitochondrial absorption Cocheme et al. 2009; Mayhew et al. 1978).

Spectrophotometric detection of these intermediates often requires strict control of experimental conditions, such as oxygen tension, pH, and the presence of reducing agents (e.g., NADH, dithionite) or enzymatic systems (e.g., NADPH:cytochrome P450 reductase). These factors influence the equilibrium between fully oxidized, semiquinone, and fully reduced forms of the compound. By plotting the absorbance as a function of time or reductant concentration, it is possible to infer the kinetics of radical formation and decay, as well as the redox potential and stability of the intermediate species.

In certain cases, differential spectrophotometry (i.e., subtraction of baseline spectra) can enhance the detection of weak or overlapping signals. Furthermore, kinetic analysis of spectral changes can reveal mechanistic aspects of redox cycling, such as disproportionation reactions or the role of molecular oxygen in promoting radical turnover (Thor et al. 1982)

Domain of Applicability

Isolated mitochondria, cultured cells and whole organisms like yeast, worms, flies, rodents and plants generate O2° in the presence of redox chemicals like Paraquat mostly increasing mitochondrial oxidative damage (Mason, 1990; Vanfleteren, 1993, Sturz and Culotta, 2002; Van Remmen et al.,2004; Bonilla et al., 2006). Mitochondria as a major site of mitochondrial superoxide production by PQ are supported in rodents, flies and yeast. Thus, mice heterozygous for MnSOD (the isoform of superoxide dismutase locate in the mitochondrial matrix) (Van Remmen et al., 2004) and flies silenced for MnSOD (Kirby et al., 2002) show greater sensitivity to PQ than the control; flies overexpressing catalase in mitochondria are resistant to PQ, whereas enhancement of cytosolic catalase was not protective (Mockett et al., 2003); human peroxiredoxin 5 in mitochondria protects yeast more efficiently against PQ than expression in the cytosol (Tien Nguten-nhu et al., 2003). Complex I has a highly conserved subunit composition in eukaryotes (Cardol, 2011). Fourteen subunits are considered to be the minimal structural requirement for physiological functionality of the enzyme. These units are well conserved between bacterial (E. coli), human (H. sapiens), and bovine (B. Taurus) (Ferguson, 1994; Vogel et al., 2007). However, the complete structure of Complex I is reported to contain between 40 to 46 subunits and the number of subunits differs, depending on the species (Gabaldon 2005; Choi et al., 2008). Complex I is well-conserved across species, from lower organism to mammals. In vertebrates it consists of at least 46 subunits (Hassinen, 2007), including human in which 45 subunits were found (Vogel et al., 2007). Moreover, enzymatic and immunochemical evidence indicate a high degree of similarity between mammalian and fungal counterparts (Lummen, 1998). Mammalian complex I structure (Vogel et al., 2007) and activity is characterised in detail, referring to different human organs including brain. There is also substantial amount of studies performed on human muscles, brain, liver as well as bovine heart (Okun et al., 1999). Yeasts lack Complex I but reduce PQ in dependence on NADPH by intramitochondrial NADPH dehydrogenases (Cocheme and Murphy, 2008). Cytochrome bc1 complexes (Complex III) are found in the plasma membranes of photosynthetic and respiring bacteria and in the inner mitochondrial membrane of all eukaryotic cells (Trumpower, 1990). In all of these species the bc1 complex contain three electron transfer proteins and transfer electrons from a low-potential quinol to a higher-potential c-type cytochrome (Trumpower, 1990). The number of subunits in the bc1 varies between 3 catalytic subunits in some bacteria and 11 subunits in the mitochondrial bc1 (Trumpower, 1990).

Evidence for Chemical Initiation of this Molecular Initiating Event (MIE)

The most studied examples of chemicals that accept an electron from the mitochondrial respiratory chain and undergo redox cycling in dopaminergic neurons are the three bipyridyl herbicides paraquat, diquat and benzyl viologen. Substantial evidence has accumulated in the existing literature suggesting a role for these chemical, and paraquat in particular, and this AOP. Therefore, the redox cycler parquat will be discussed in the context of all KEs identified in this AOP.

Paraquat as a mitochondrial electron acceptor

The cellular toxicity of PQ is essentially due to its redox cycling abilities. Mitochondria are a major source of PQ-induced ROS production in brain (Castello et al., 2007; Figure 2). The early involvement of mitochondria in PQ-induced oxidative stress has been also demonstrated in whole cells overexpressing reduction-oxidation sensitive fluorescent proteins targeted to mitochondria or the cytosol (Rodriguez-Rocha, 2013; Filograna et al., 2016). Both Complex I (Cocheme and Murphy, 2008) and Complex III (Castello et al., 2007; Drechsel and Patel, 2009) have been involved in PQ radicalisation. In Castello et al. (2007), the redox cycle-initiating electrons are accepted from complex III and to a minor part by complex I as inhibition of complex I by rotenone only partially inhibited PQ-induced ROS formation in isolated brain mitochondria or rat midbrain cultures, while PQ-induced ROS formation in these systems was completely blocked after inhibition of complex III by using antimycin A (Castello et al., 2007; Drechsel and Patel, 2009). That complex I is not the major source of electrons triggering PQ toxicity is supported by Choi et al., (2008) who demonstrated that silencing a major component of complex I abolishing its activity does not protect against PQ-dependent dopaminergic cell death. On the other hand, Cocheme and Murphy (2008) demonstrated that PQ accumulates into yeast and bovine heart mitochondrial matrix in dependence on mitochondrial membrane potential. In heart mitochondria, PQ is then reduced mainly by Complex I forming the radical which rapidly react with O2 to give O2. The Authors explain this discrepancy with differences existing between brain and heart mitochondria (Cocheme and Murphy, 2008; Drechsel and Patel, 2009). The involvement of mitochondrial enzymes other than Complex I and III (VDAC and Cytb5, located at the external mitochondrial membrane) remains controvertial (Shimada et al., 2009; Nikiforova et al., 2014) and potentially excluded by the recent observation that the main site of PQ reduction is inside mitochondria (Nikiforova et al., 2014).

General characteristics of other mitochondrial redox cyclers

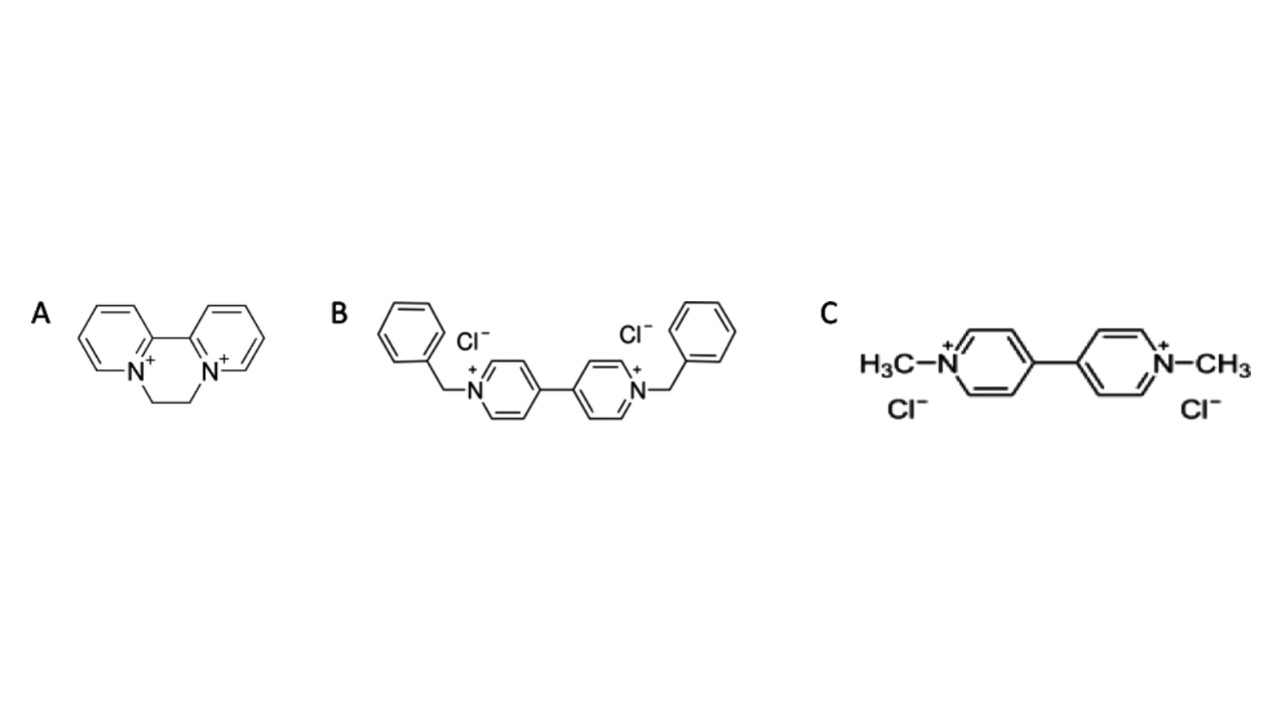

Other mitochondrial redox cyclers include two other bipyridyl herbicides, diquat and benzyl viologen (Figure 4 A and B). These share common structural features with paraquat (Figure A.27C): all compounds are composed of two aromatic rings containing a positively charged nitrogen and are thus good electron acceptors and redox cyclers (Drechsel and Patel, 2009; Sandy et al., 1986).

Fig. 4. Molecular structures of: (A) diquat, (B) benzyl viologen, (C) paraquat (Copyright Drechsel and Patel, 2009, Fig. 1. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society of Toxicology)

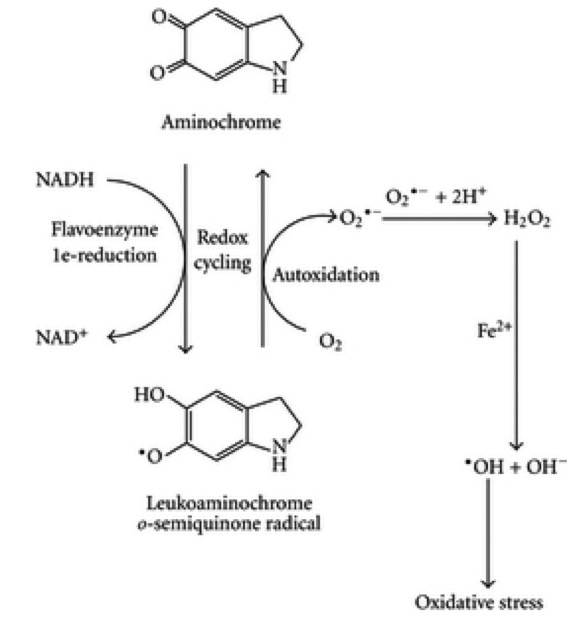

Quinones (i.e. menadione, Adriamycin) and nitroaromatic compounds (i.e. nitrofurantoin) also radicalise following one electron reduction by mitochondrial reductases (complex I and III and external mitochondria NADH-oxidoreductase) establishing a redox cycle (Frei et al., 1986; Nikiforova et al., 2014). Intriguingly, free cytosolic dopamine spontaneously oxidises to produce different quinones like dopamine-o-quinone and aminochrome. Aminochrome can undergo a one-electron reduction by NAD (P)H flavoproteins generating a leukoaminochrome-o-semiquinone radical and giving rise to redox cycle with production of superoxide anion (Zoccarato et al., 2005; Munoz et al., 2012).

Fig. 5 One electron reduction of aminochrome (adapted from Mu~ noz et al., 2012, fig. 6, CC-BY) Aminochrome has been recently suggested to play a role in the death of dopaminergic neurons containing neuromelanin triggering oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction, the formation of a-synuclein and impaired protein degradation (Sandy et al., 1986; Drechsel and Patel, 2009).

References

Bonila E, Medina-Leendertz S, Villalobos V, Molero L, Bohorquez A, 2006. Paraquat-induced oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster: effects of melatonin, glutathione, serotonin, minocycline, lipoic acid and ascorbic acid. Neurochemical Research, 31, 1425–1432.

Brand MD, 1995. Measurement of mitochondrial protonmotive force. In: Brown GC and Cooper CE (eds.). ‘‘Bioenergetics—A Practical Approach.’’ Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy. IRL Press, Oxford, pp. 39–62.

Brand MD. Mitochondrial generation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide as the source of mitochondrial redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016 Nov;100:14-31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001. Epub 2016 Apr 13. PMID: 27085844.

Brand MD. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp Gerontol. 2010 Aug;45(7-8):466-72. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003. Epub 2010 Jan 11. PMID: 20064600; PMCID: PMC2879443.

Bus JS, Aust SD, Gibson JE. Superoxide- and singlet oxygen-catalyzed lipid peroxidation as a possible mechanism for paraquat (methyl viologen) toxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974 Jun 4;58(3):749-55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(74)80481-x. PMID: 4365647.

Bus JS, Gibson JE. Paraquat: model for oxidant-initiated toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 1984 Apr;55:37-46. doi: 10.1289/ehp.845537. PMID: 6329674; PMCID: PMC1568364.

Cadenas E, Boveris A, Ragan CI, Stoppani AO. Production of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide by NADH-ubiquinone reductase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase from beef-heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977 Apr 30;180(2):248-57. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90035-2. PMID: 195520.

Cardol P, 2011. Mitochondrial NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) in eukaryotes: a highly conserved subunit composition highlighted by mining of protein databases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1807, 1390–1397.

Castello PR, Drechsel DA, Patel M, 2007. Mitochondria are a major source of paraquat-induced reactive oxygen species production in the brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 282, 14186–14193. http://www.jbc.org/content/282/19/14186.full.pdf Fig 2, p.14188.

Cocheme HM, Murphy MP, 2008. Complex I is the major site of mitochondrial superoxide production by paraquat. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283, 1786–1798.

Cocheme HM, Murphy MP, 2009. Chapter 22 The uptake and interactions of the redox cycler paraquat with mitochondria. Methods in Enzymology, 456, 395–417. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04422-4

Cohen GM, d’Arcy Doherty M, 1987. Free radical mediated cell toxicity by redox cycling chemicals. British Journal of Cancer. Supplement, 8, 46–52.

Choi WS, Kruse SE, Palmiter R, Xia Z, 2008. Mitochondrial complex I inhibition is not required for dopaminergic neuron death induced by rotenone, MPP, or paraquat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105, 15136–15141.

Dranka BP, Zielinka J, Kanthasamy AG, Kalyanaraman B, 2012. Alterations in bioenergetics function induced by Parkinson’s disease mimetic compounds: lack of correlation with superoxide generation. Journal of Neurochemistry, 122, 941–951.

Drechsel DA, Patel M, 2009. Differential contribution of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes to reactive oxygen species production by redox cycling agents implicated in parkinsonism. Toxicological Sciences, 112(2), 427–434. http://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfp223

Drechsel DA, Patel M. Chapter 21 Paraquat-induced production of reactive oxygen species in brain mitochondria. Methods Enzymol. 2009a;456:381-93. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04421-2. PMID: 19348900.

Dröse S, Bleier L, Brandt U. A common mechanism links differently acting complex II inhibitors to cardioprotection: modulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Mol Pharmacol. 2011 May;79(5):814-22. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.070342. Epub 2011 Jan 28. PMID: 21278232.

Dröse S, Brandt U. The mechanism of mitochondrial superoxide production by the cytochrome bc1 complex. J Biol Chem. 2008 Aug 1;283(31):21649-54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803236200. Epub 2008 Jun 3. PMID: 18522938.

Dröse S, Hanley PJ, Brandt U. Ambivalent effects of diazoxide on mitochondrial ROS production at respiratory chain complexes I and III. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Jun;1790(6):558-65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.01.011. Epub 2009 Feb 6. PMID: 19364480.

Dutton PL, Moser CC, Sled VD, Daldal F, Ohnishi T. A reductant-induced oxidation mechanism for complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998 May 6;1364(2):245-57. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00031-0. PMID: 9593917.

Erecińska M, Wilson DF. The effect of antimycin A on cytochromes b561, b566, and their relationship to ubiquinone and the iron-sulfer centers S-1 (+N-2) and S-3. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1976 May;174(1):143-57. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90333-7. PMID: 180891.

Ferguson SJ, 1994. Similarities between mitochondrial and bacterial electron transport with particular reference to the action of inhibitors. Biochemical Society Transactions, 22, 181–193. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 8206221

Filograna R, Godena VK, Sanchez-Martinez A, Ferrari E, Casella L, Beltramini M, Bubacco L, Whitworth AJ, Bisaglia M, 2016. SOD-mimetic M40403 is protective in cell and fly models of paraquat toxicity: implications for Parkinson disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Friedrich T, van Heek P, Leif H, Ohnishi T, Forche E, Kunze B, Jansen R, TrowitzschKienast W, Hofle G, Reichenbach H, 1994. Two binding sites of inhibitors in NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). Relationship of one site with the ubiquinone-binding site of bacterial glucose: ubiquinone oxidoreductase. European Journal of Biochemistry, 219, 691–698.

Frei B, Winterhalter KH, Richter C, 1986. Menadione- (2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone-) dependent enzymatic redox cycling and calcium release by mitochondria. Biochemistry, 25, 4438–4443.

Fussell KC, Udasin RG, Gray JP, Mishin V, Smith PJ, Heck DE, Laskin JD. Redox cycling and increased oxygen utilization contribute to diquat-induced oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in Chinese hamster ovary cells overexpressing NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011 Apr 1;50(7):874-82. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.035.

Gabaldon T, Rainey D, Huynen MA, 2005. Tracing the evolution of a large protein complex in the eukaryotes, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Complex I). Journal of Molecular Biology, 348, 857–870.

Gardner PR, 2002. Aconitase: sensitive target and measure of superoxide. Methods in Enzymology, 349, 9–23.

Greenamyre JT, Sherer TB, Betarbet R, and Panov AV, 2001. Critical review Complex I and Parkinson’s Disease. Life, 52, 135–141.

Grivennikova VG, Vinogradov AD, 2013. Mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry (Mosc), 78, 1490–1511.

Guillaud F, Dröse S, Kowald A, Brandt U, Klipp E. Superoxide production by cytochrome bc1 complex: a mathematical model. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 Oct;1837(10):1643-52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.05.358. Epub 2014 Jun 7. PMID: 24911293.

Handy DE, Loscalzo J. Redox regulation of mitochondrial function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012 Jun 1;16(11):1323-67. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4123. Epub 2012 Feb 3. PMID: 22146081; PMCID: PMC3324814.

Hassan HM. Exacerbation of superoxide radical formation by paraquat. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:523-32. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05072-2. PMID: 6328203.

Hassinen I, 2007. Regulation of mitochondrial respiration in heart muscle. In: Schaffer S. (ed.). Mitochondria– The Dynamic Organelle. Springer ISBN-13: 978-0-387-69944-8.

Kappus H, 1986. Overview of enzyme systems involved in bio-reduction of drugs and in redox cycling. Biochemical Pharmacology, 35, 1–6.

Kowaltowski AJ, de Souza-Pinto NC, Castilho RF, Vercesi AE. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009 Aug 15;47(4):333-43. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.004. Epub 2009 May 8. PMID: 19427899.

Lambert AJ, Brand MD. Inhibitors of the quinone-binding site allow rapid superoxide production from mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). J Biol Chem. 2004 Sep 17;279(38):39414-20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406576200. Epub 2004 Jul 15. PMID: 15262965.

Lim LO, Bortell R, Neims AH, 1986. Nitrofurantoin inhibition of mouse liver mitochondrial respiration involving NAD-linked substrates. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 84, 493–499.

Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006 Oct 19;443(7113):787-95. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. PMID: 17051205.

Lopert P, Day BJ, Patel M, 2012. Thioredoxin reductase deficiency potentiates oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in dopaminergic cells. Public Library of Science (PLoS ONE), 7, e50683. L€ ummen P, 1998. Complex I inhibitors as insecticides and acaricides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1364, 287–296.

Kirby K, Hu J, Hilliker AJ, Phillips JP, 2002. RNA interference-mediated silencing of Sod2 in Drosophila leads toearly adult-onset mortality and elevated endogenous oxidative stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99, 16162–16167.

Mayhew SG. The redox potential of dithionite and SO-2 from equilibrium reactions with flavodoxins, methyl viologen and hydrogen plus hydrogenase. Eur J Biochem. 1978 Apr 17;85(2):535-47. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12269.x. PMID: 648533.

Mason RP, 1990. Redox cycling of radical anion metabolites of toxic chemicals and drugs and the Marcus theory of electron transfer. Environmental Health Perspectives, 87, 237–243.

McCord JM and Fidovich I, 1968. The reduction of cytochrome c by milk xanthine oxidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 243, 5733–5760.

Medvedev ES, Couch VA, Stuchebrukhov AA. Determination of the intrinsic redox potentials of FeS centers of respiratory complex I from experimental titration curves. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Sep;1797(9):1665-71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.05.011. Epub 2010 Jun 1. PMID: 20513348; PMCID: PMC4220741.

Miwa S, St-Pierre J, Partridge L, Brand MD. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production by Drosophila mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003 Oct 15;35(8):938-48. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00464-7. PMID: 14556858.

Minakata K, Suzuki O, Asano M. Rapid quantitative analysis of paraquat by electron spin resonance spectroscopy. Forensic Sci Int. 1988 May;37(3):215-22. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(88)90187-9. PMID: 2841209.

Mockett RJ, Bayne AC, Kwong LK, Orr WC, Sohal RS, 2003. Ectopic expression of catalase in Drosophila mitochondria increases stress resistance but not longevity. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 34, 207–217.

Munoz P, Huenchuguala S, Paris I, Segura-Aguilar J, 2012. Dopamine oxidation and autophagy. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease, 2012, 920953. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230830981_Dopamine_ Oxidation_and_Autophagy P.6, Fig. 6

Murphy MP, Smith RA, 2007. Targeting antioxidants to mitochondria by conjugation to lipophilic cations. Annual. Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 47, 629–656.

Nikiforova AB, Saris NE, Kruglov AG, 2014. External mitochondrial NADH-dependent reductase of redox cyclers: VDAC1 or Cyb5R3? Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 74, 74–84.

Okun JG, L€ ummen P, Brandt U, 1999. Three classes of inhibitors share a common binding domain in mitochondrial Complex I (NADH:Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase). Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274, 2625–2630. doi:10.1074/ jbc.274.5.2625

Ohnishi T. Iron-sulfur clusters/semiquinones in complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998 May 6;1364(2):186-206. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00027-9. PMID: 9593887.

Quinlan CL, Gerencser AA, Treberg JR, Brand MD. The mechanism of superoxide production by the antimycin-inhibited mitochondrial Q-cycle. J Biol Chem. 2011 Sep 9;286(36):31361-72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.267898. Epub 2011 Jun 27. PMID: 21708945; PMCID: PMC3173136.

Quinlan CL, Goncalves RL, Hey-Mogensen M, Yadava N, Bunik VI, Brand MD. The 2-oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes in mitochondria can produce superoxide/hydrogen peroxide at much higher rates than complex I. J Biol Chem. 2014 Mar 21;289(12):8312-25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.545301. Epub 2014 Feb 10. PMID: 24515115; PMCID: PMC3961658.

Quinlan CL, Treberg JR, Perevoshchikova IV, Orr AL, Brand MD. Native rates of superoxide production from multiple sites in isolated mitochondria measured using endogenous reporters. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012 Nov 1;53(9):1807-17. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.015. Epub 2012 Aug 17. PMID: 22940066; PMCID: PMC3472107.

Rodriguez-Rocha H, Garcia-Garcia A, Pickett C, Li S, Jones J, Chen H, Webb B, Choi J, Zhou Y, Zimmerman MC, Franco R, 2013. Compartmentalized oxidative stress in dopaminergic cell death induced by pesticides and complex I inhibitors: distinct roles of superoxide anion and superoxide dismutases. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 0, 370–383.

Sandy MS, Moldeus P, Ross D, Smith MT, 1986. Role of redox cycling and lipid peroxidation in bipyridyl herbicide cytotoxicity. Studies with a compromised isolated hepatocyte model system. Biochemical Pharmacology, 35, 3095–3101.

Sarewicz M, Borek A, Cieluch E, Swierczek M, Osyczka A. Discrimination between two possible reaction sequences that create potential risk of generation of deleterious radicals by cytochrome bc₁. Implications for the mechanism of superoxide production. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Nov;1797(11):1820-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.07.005. Epub 2010 Jul 15. PMID: 20637719; PMCID: PMC3057645.

Sawyer DT, Valentine JS, 1981. How super is superoxide? Accounts of Chemical Research, 14, 393–400.

Selivanov VA1, Votyakova TV, Pivtoraiko VN, Zeak J, Sukhomlin T, Trucco M, Roca J, Cascante M, 2011. Reactive oxygen species production by forward and reverse electron fluxes in the mitochondrial respiratory chain. PLOS Computational Biology, 7, e1001115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001115

Sharma LK, LuJ, Bai Y. Mitochondrial respiratory complex I: structure, function and implication in human diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(10):1266-77. doi: 10.2174/092986709787846578. PMID: 19355884; PMCID: PMC4706149.

Shimada H, Hirai K, Simamura E, Hatta T, Iwakiri H, Mizuki K et al., 2009. Paraquat toxicity induced by voltage- dependent anion channel 1 acts as an NADH-dependent oxidoreductase. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 284, 28642–28649.

Schweiger, Jeschke, 2001. Principles of Pulse Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Oxford University Press.

Sturtz LA, Culotta VC, 2002. Superoxide dismutase null mutants of baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods in Enzymology, 349, 167–172.

Thor H, Smith MT, Hartzell P, Bellomo G, Jewell SA, Orrenius S. The metabolism of menadione (2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone) by isolated hepatocytes. A study of the implications of oxidative stress in intact cells. J Biol Chem. 1982 Oct 25;257(20):12419-25. PMID: 6181068.

Tien Nguyen-nhu N, Knoops B, 2003. Mitochondrial and cytosolic expression of human peroxiredoxin 5 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae protect yeast cells from oxidative stress induced by paraquat. Federation of the European Biochemical Societies’s Letters (FEBS), 544, 148–152.

Trumpower BL, 1990. Cytochrome bc1 complexes of microorganisms. Microbiol Reviews, 54, 101–129.

Turrens JF, Alexandre A, Lehninger AL. Ubisemiquinone is the electron donor for superoxide formation by complex III of heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985 Mar;237(2):408-14. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90293-0. PMID: 2983613.

Turrens JF, Boveris A. Generation of superoxide anion by the NADH dehydrogenase of bovine heart mitochondria. Biochem J. 1980 Nov 1;191(2):421-7. doi: 10.1042/bj1910421. PMID: 6263247; PMCID: PMC1162232.

Ullrich V, Schildknecht S. Sensing hypoxia by mitochondria: a unifying hypothesis involving S-nitrosation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014 Jan 10;20(2):325-38. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4788. Epub 2012 Sep 11. PMID: 22793377.

Van Remmen H, Qi W, Sabia M, Freeman G, Estlack L, Yang H, Mao Guo Z, Huang TT, Strong R, Lee S, Epstein CJ, Richardson A, 2004. Multiple deficiencies in antioxidant enzymes in mice result in a compound increase in sensitivity to oxidative stress. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 36, 1625–1634.

Vanfleteren JR, 1993. Oxidative stress and ageing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochemical Journal, 292, 605–608.

Verkhovskaya ML, Belevich N, Euro L, Wikström M, Verkhovsky MI. Real-time electron transfer in respiratory complex I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Mar 11;105(10):3763-7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711249105. Epub 2008 Mar 3. PMID: 18316732; PMCID: PMC2268814.

Vogel RO, van den Brand MA, Rodenburg RJ, van den Heuvel LP, Tsuneoka M, Smeitink JA, Nijtmans LG, 2007. Investigation of the complex I assembly chaperones B17.2L and NDUFAF1 in a cohort of CI deficient patients. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 91, 176–182.

Votyakova TV, Reynolds IJ. DeltaPsi(m)-Dependent and -independent production of reactive oxygen species by rat brain mitochondria. J Neurochem. 2001 Oct;79(2):266-77. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00548.x. PMID: 11677254.

Wong HS, Dighe PA, Mezera V, Monternier PA, Brand MD. Production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide from specific mitochondrial sites under different bioenergetic conditions. J Biol Chem. 2017 Oct 13;292(41):16804-16809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.789271. Epub 2017 Aug 24. PMID: 28842493; PMCID: PMC5641882.

Zhang H, Osyczka A, Dutton PL, Moser CC. Exposing the complex III Qo semiquinone radical. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007 Jul;1767(7):883-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.04.004. Epub 2007 May 1. PMID: 17560537; PMCID: PMC3554237.

Zhang L, Yu L, Yu CA. Generation of superoxide anion by succinate-cytochrome c reductase from bovine heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1998 Dec 18;273(51):33972-6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.33972. PMID: 9852050.