The authors have designated this AOP as all rights reserved. Re-use in any form requires advanced permission from the authors.

AOP: 622

Title

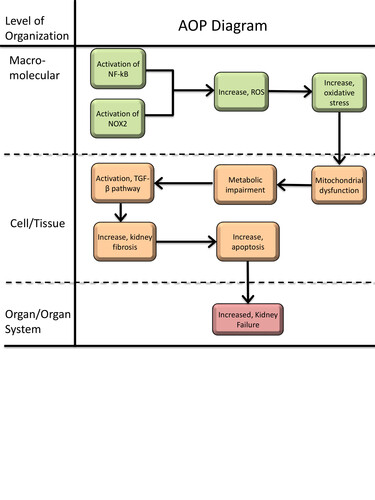

Calcineurin inhibitor induced nephrotoxicity leading to kidney failure

Short name

Graphical Representation

Point of Contact

Contributors

- Kate Liang

Coaches

OECD Information Table

| OECD Project # | OECD Status | Reviewer's Reports | Journal-format Article | OECD iLibrary Published Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

This AOP was last modified on February 27, 2026 07:18

Revision dates for related pages

| Page | Revision Date/Time |

|---|---|

| Increased activation, Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) | August 27, 2023 03:08 |

| Activation, NADPH Oxidase | September 16, 2017 10:17 |

| Increase, Reactive oxygen species | June 12, 2025 01:27 |

| Increase, Oxidative Stress | February 11, 2026 07:05 |

| Increase, Mitochondrial dysfunction | February 11, 2026 07:06 |

| Activation, TGF-beta pathway | September 16, 2017 10:17 |

| Increase, Apoptosis | April 15, 2017 16:17 |

| Increased, Kidney Failure | January 16, 2019 08:57 |

| Metabolic impairment | February 06, 2026 08:28 |

| Increase, kidney fibrosis | February 27, 2026 04:34 |

| Cyclosporin | May 18, 2017 08:31 |

| Tacrolimus (also FK506) | June 27, 2021 02:54 |

Abstract

Tacrolimus (TAC) and cyclosporin A (CsA) are widely used calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) whose therapeutic efficacy (i.e. immunosuppression) is limited by nephrotoxicity, particularly in kidney transplant recipients. This adverse outcome pathway (AOP) outlines the mechanistic sequence of events leading from CsA or TAC exposure to chronic kidney injury. Despite the molecular initiating event remains unknown, the first recorded key event is the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and induction of NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2). These upstream events promote increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), a well-established response observed in vitro and in vivo. Elevated ROS levels drive oxidative stress, characterized by depletion of antioxidant capacity and increased oxidative damage markers. Oxidative stress leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, including loss of membrane potential, impaired respiration, and reduced ATP production. These mitochondrial changes are accompanied by metabolic disturbances, such as alterations in TCA cycle intermediates, amino acid pathways, and fatty acid metabolism, described across cell-based systems and in vivo studies. Metabolic impairment and cellular stress are associated with increased TGF-β signalling, a central event consistently linked to CNI-induced tubular injury and fibrosis. Persistent activation of TGF-β pathways contributes to extracellular matrix deposition, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis. These tissue-level alterations ultimately culminate in decreased kidney function, reflected clinically by reduced GFR and progression toward chronic kidney disease. This AOP provides a structured framework to integrate mechanistic evidence, identify key data gaps, and support the development of new approach methodology-based approaches for assessing CNI nephrotoxicity.

AOP Development Strategy

Context

This AOP describes the sequence of key events (KE’s) that link the usage of CNIs to nephrotoxicity and the adverse outcome kidney failure. CNIs are immunosuppressive drugs that inhibit calcineurin by binding to immunophilins, such as cyclophilin and FK-binding proteins (1). Calcinuerin is a crucial enzyme for activating T-cells. Blockage of the enzyme leads to reduction of interleukin-2 and T-cell proliferation. Currently, the two most commonly used systemic CNIs are TAC and CsA, typically administered orally. Indication for systemic CNI treatment is solid organ transplantation and are used to effectively manage several autoimmune disorders, including lupus nephritis, idiopathic inflammatory myositis and interstitial lung disease. CNIs are associated with both acute and chronic kidney damage due to its narrow therapeutic window (2, 3). Nephrotoxicity secondary to CNIs occurs in liver (52%), heart (20–75%) and kidney (76–94%) transplant recipients (4). Risk factors for CNI toxicity include volume depletion, diuretic use, older donor age, exposure to high CNI doses, concomitant use of nephrotoxic drugs (particularly NSAIDs), concomitant use of CYP3A4/5 or P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) inhibitors, and genetic polymorphisms affecting CYP3A4/5 and P-glycoprotein function. CNI are also available in a topical form, which is used for mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. However, because of the route of exposure, nephrotoxicity is not an issue for topical CNIs.

-

-

- Molecular Initiating Event: Unkown

-

As CNI-induced nephrotoxicity involves several mechanisms, a well-defined MIE cannot be found. CNI-induced nephrotoxicity can be a result of vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriole, leading to ischemia in the kidney (2). However, there is also a direct toxic effect, such as increased oxidative stress, of CNI’s on tubular epithelial cells, as has been shown in multiple studies (5-7). In tubular epithelial cells, the influx transporter, if existing, of CNI’s is unknown, and the only efflux transporter that has been identified to transport CNI’s is P-glycoprotein (ABCB1). Identifying the initial interaction of CNI with kidney cells, and consequently the MIE, remains challenging.

-

-

- Key Event 1: Activation of NF-kB and NOX2

-

NF-κB, a downstream target of CNI, is activated in tubular cells after treatment with TAC and CsA (8). The pathway of NF-κB activation is not exactly known, but it could be activated by angiotensin II (9), degradation of I-κBα (10) or upstream kinases: c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) and Janus Kinase (JAK)(11). A transcriptomics analysis of mouse cortical proximal tubular cells treated with TAC and CsA showed significant activation of NF-κB and pro-inflammatory cytokines which are strongly associated with kidney disease, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein -1 (MCP-1) and Rantes (11). Inhibition of Nf-κB after CNI exposure in several in vivo studies have shown attenuation of nephropathy, indicating an important role of the factor in the development of CNI nephrotoxicity (12, 13). Additionaly, activation of NF-κB leads to upregulation of NADPH oxidases (NOX) in the tubule (14).

The primary function of NOX are generating reactive oxidative species (ROS) by transferring one electron to dioxygen leading to the product superoxide. Isoforms NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4 are expressed in the kidney and known sources of ROS production (15). NOX2 in particular is associated with CsA-induced kidney fibrosis and chronic nephrotoxicity (16, 17). Furthermore, NOX2 was significantly increased in the tubule and interstitial cells after immunohistochemical analyses of kidney biopsies from liver transplant recipients with CNI nephrotoxicity after exposure to TAC or CsA (16). Moreover, TAC increases ROS via NOX in the glomerulus, especially in endothelial glomerular cells (18).

-

-

- Key Event 2: ROS production

-

Mitochondria generate about 90% of cellular ROS, making them the primary source of ROS in renal proximal tubules (19). The kidney is highly metabolically active, abundant in mitochondira, and, therefore, particularly susceptible to ROS. When ROS production exceeds the cell’s antioxidant capacity, oxidative stress occurs, damaging cellular components and contributing to chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression (20).

In a proximal tubular cell line derived from a healthy human adult male kidney (human kidney-2 (HK-2) cells), TAC increased the intracellular ROS levels by 1.67 fold compared to the control group (21). Exposure to TAC (30 µM and 60 µM, for 24 h) in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derived kidney organoids significantly increased ROS levels detected by immunofluorescence staining with MitoSOX Red (22). Moreover, damaged mitochondria with spherical shapes and cristolysis were observed in the kidney organoids after TAC exposure, and quantification with Mitrotracker showed increased mitochondrial stress (22).

In addition to increasing ROS, CNI also disrupt antioxidant defense systems leading to imbalances in the redox environment, amongst which decreasing glutathione (23). Moreover, CsA exposure damages the inner and outer mitochondrial membrane, resulting in mitochondrial permeability transition pores. The exact mechanism has yet to be elucidated, but it has been suggested that oxidative stress may alter thiol groups of membrane proteins, leading to misfolding and clustering of these proteins and resulting in opening of membrane pores (23). Subsequently, apoptotic mediators, such as cytochrome c, are released into the cytosol. Moreover, increased ROS might lead to increased expression of dynamin related protein 1, a GTPase that regulates mitochondrial fission and decreased expression of mitofusin 2 and optic atrophy protein 1 (Opa1), both important proteins in the mitochondrial fusion process (24, 25). Consequently, increased fission and decreased fusion takes place in the mitochondria, dysregulating the apoptotic pathways (26, 27).

-

-

- Key Event 3: Oxidative stress

-

Oxidative stress, defined by an imbalance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant systems, is harmful to cellular health due to the excessive production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (28). Evidence strongly indicates this to be a KE in TAC-induced nephrotoxicity (7, 29-31). A study in (porcine-derived) LLC-PK1 cells demonstrated an increase in hydrogen peroxide, a direct indicator of oxidative stress upon TAC treatment with increased expression of pro-oxidant enzymes and reduced activity of antioxidant pathways, resulting in cellular damage and apoptosis (7).

In vitro studies using kidney cell lines and kidney organoids offer deeper insights into the cellular and molecular mechanisms of TAC-induced oxidative stress. Kidney proximal tubular epithelial cells exposed to TAC exhibit upregulation of oxidative stress markers and mitochondrial dysfunction (32). These findings are supported by several other studies, which reported downregulation of antioxidants and upregulation of NOX2 after TAC in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, treatment with coenzyme Q10 has been shown to alleviate TAC-induced kidney dysfunction by preventing ROS production and improving mitochondrial respiration in HK-2 cells (33).

In vivo studies in rodents further clarify the mechanisms by which TAC induces oxidative stress (34). Further, in an intracellular metabolomics analyses, mice treated with CNIs showed increased oxidative stress by either decreased glutathione or decreased glutathione peroxidase activity in the kidney cells (7). Rabbits exposed to TAC showed increased oxidative stress caused by impairments in antioxidant response (35). Additionally, the anti-oxidant cilastatin counteracted TAC-induced nephrotoxicity in rat proximal tubular cells, resulting in reduced oxidative DNA damage (33). Overall, the use of antioxidants and oxidative stress inhibitors has shown potential in mitigating the oxidative damage caused by TAC in vitro and in vivo, suggesting possible therapeutic strategies to counteract its nephrotoxic effects (36).

Human studies have also indicated that patients undergoing TAC therapy exhibit decreased antioxidant defenses (37, 38) including reduced glutathione levels. Additionally, increased levels of malondialdehyde, indicating a process called lipid peroxidation, as a result of oxidative stress have been found in patients. Collectively, these findings underscore oxidative stress as an early key event in TAC exposure, potentially initiating the cascade of events that eventually leads to kidney failure.

-

-

- Key Event 4: Mitochondrial dysfunction

-

The kidney, with its high energy demands for reabsorption processes across different nephron segments, relies heavily on mitochondria. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a significant factor, leading to impaired ATP production, increased ROS levels, metabolic deficiencies and damage that directly impact kidney function (39).

In vitro studies using HK-2 cells have shown that TAC exposure causes a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. These effects were accompanied by decreased oxygen consumption rates and impaired ATP synthesis, further confirming mitochondrial dysfunction (33). Also kidney organoids treated with TAC exhibit significant mitochondrial damage, including loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, increased ROS production, and activation of autophagy as a cellular response to mitochondrial stress (40). Additionally, coenzyme Q10, a mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant, could partly mitigate the mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress induced by TAC (41).

In vivo studies have shown that TAC administration in mice results in increased mitochondrial ROS production and decreased antioxidant defenses, exacerbating mitochondrial dysfunction and kidney injury (42). Electron microscopy of kidney tissues from TAC-treated mice revealed a reduction in both the number and volume of mitochondria, along with structural abnormalities (33), which was also demonstrated in rats, with the remaining mitochondria appearing fragmented (fission and fusion) (33). These findings suggest that TAC not only impairs mitochondrial function but also affects mitochondrial biogenesis and morphology.

Long-term exposure of human patients to TAC leads to progressive kidney failure, characterized by interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and inflammation (43), all of this potentially linked to mitochondrial damage. In agreement, ultrastructural analysis of kidney biopsies from patients treated with TAC revealed mitochondrial swelling, cristae disruption, and increased ROS production (44).

-

-

- Key Event 5: Metabolic impairment

-

Cell metabolism impairment is a critical event in the pathway of TAC-induced nephrotoxicity, encompassing various disruptions that contribute to kidney damage and dysfunction (42, 45). Within mitochondria, the TCA cycle, fueled by glycolysis-derived pyruvate, produces energy-rich nucleotides and accumulates coenzyme NADH+ in the presence of oxygen (46, 47). NADH is processed by the mitochondrial respiration chain complex (subunits I-IV), along with cytochrome C and coenzyme Q10, creating a gradient that converts ADP into ATP, which is then transported into the cytosol (48).

In vivo studies have provided additional insights into the mechanisms of TAC-induced nephrotoxicity. For instance, in a mouse model, TAC administration resulted in significant alterations in kidney metabolism, including changes in metabolites such as L-valine and D-glucose, indicative of disrupted mitochondrial function (42, 45). Treatment with non-toxic doses of TAC showed impairments in the TCA cycle, including increased folate metabolism, citric acid metabolism, and glutathione synthesis, indicating a metabolic switch as a reaction to oxidative stress (G) (42, 45). In proximal tubule cells, L-carnitines were the most differentially accumulated metabolites upon TAC exposure in. Other in vitro studies using kidney cell lines have also demonstrated the impact of TAC on cellular metabolism including mitochondrial function disruption leading to decreased ATP production and increased ROS production (49, 50). These metabolic changes induce cellular stress and apoptosis, contributing to tubular dysfunction and fibrosis. Additionally, they found that TAC inhibits key metabolic enzymes, such as pyruvate dehydrogenase and citrate synthase, further impairing cellular energy metabolism. These findings highlight the direct effects of TAC on kidney cell metabolism and its role in nephrotoxicity development.

Furthermore, another study found TAC-induced metabolic impairment involved alterations in amino acid metabolism, with decreased levels of essential amino acids such as valine and leucine (7). These changes impair protein synthesis and cellular repair mechanisms, further exacerbating kidney damage.

In clinical settings, TAC-induced nephrotoxicity is often observed in kidney transplant recipients (50). Studies have shown that TAC can cause metabolic disturbances, including hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, which are risk factors for CKD (51). TAC impairs glucose metabolism by reducing insulin secretion and increasing insulin resistance, leading to hyperglycemia (52). Additionally, the same study found TAC linked to alterations in lipid metabolism, resulting in elevated levels of cholesterol and triglycerides. These metabolic changes exacerbate kidney injury by promoting oxidative stress and inflammation within the kidney.

-

-

- Key Event 6: Aberrant TGF-βeta

-

Exposure to TAC or CsA has been associated with significant alterations in TGF-β expression in the kidney, contributing to cytoxicity and fibrosis (53). An increased TGF-β expression has been observed with an aberrant activation of the TGF-β receptor stimulating the smad-mediated production of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, including collagen and fibronectin, features of fibrosis (49, 54). In transplant recipients, long-term treatment with TAC or CsA resulted in elevated intrarenal expression of TGF-β, collagen, fibronectin, matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP-2), and osteopontin, with TAC showing more pronounced effects than CsA (53). The TGF-β-inducible gene-H3 is a product induced by TGF-β1 and plays a role in the fibrotic response. In vitro studies have demonstrated that TAC induces fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition via a TGF-β-dependent mechanism, which is an indication of fibrosis (55). This process involves the inhibition of the calcineurin (Cn)/nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) axis, induction of TGF-β1 ligand secretion, and receptor activation in kidney fibroblasts.

Furthermore, anti-TGF-β treatment in animal models has been shown to prevent nephrotoxicity induced by CNIs, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting the TGF-β pathway to mitigate kidney fibrosis (56).

-

-

- Key Event 7: Increase, kidney fibrosis

-

TAC-treated kidneys exhibit significant evidence of kidney fibrosis, including increased expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), indicating fibroblast activation (55, 57). Nitric oxide modulation has been proposed to affect fibrosis by altering TGF-β1 expression, leading to increased matrix deposition and decreased matrix degradation through increased plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (58). In addition to increased TGF-β expression, macrophage infiltration and cellular proliferation are critical cellular players contributing to tubulointerstitial fibrosis (59). Cellular proliferation occurs both in the tubular and interstitial regions, starting in the medulla and progressing to fibrotic areas. Macrophages, which produce pro-fibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β and platelet-derived growth factor, may infiltrate during the early phases of fibrosis (60). This infiltration is potentially related to increased expression of osteopontin (OPN), a chemoattractant for macrophages, following CsA exposure (61).

In vitro studies on PTECs have shown that both TAC and CsA induce significant OPN mRNA expression (62). Treatment of mice with TGF-β resulted in increased intra-renal OPN mRNA and protein expression. In TAC-treated animals, a parallel increase in OPN and TGF-β mRNA was observed. Anti-TGF-β antibody treatment in vitro inhibited both TGF-β and OPN mRNA expression in PTECs, and similar results were obtained in vivo with CsA-treated mice (63). In support, OPN-deficient mice exhibit less severe CsA nephrotoxicity, characterized by reduced interstitial collagen deposition and macrophage infiltration, compared to control mice (61). Macrophage influx has been correlated with apoptosis in kidney tissue of CsA-treated rats (64). Similarly, OPN expression has been associated with increased microvascular injury in CsA nephrotoxicity, suggesting it could be an early marker of CNI toxicity (65).

-

-

- Key Event 8: Apoptosis

-

TAC and CsA have been directly related to cellular damage that activate apoptotic pathways (5, 6), which is primarily driven by oxidative stress and direct toxic effect on tubular cells (7). Additionally, TAC can activate the Fas system, a critical pathway in apoptosis, leading to increased cell death in kidney tissues (66). Treatment with TAC and CsA activates the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway, leading to the upregulation of CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein), a key mediator of ER stress-induced apoptosis (67). These cellular events culminate in the activation of caspase-12 and caspase-3 (68), executing the apoptotic process. Furthermore, in a study involving mice, TAC administration led to tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, with a marked increase in apoptotic cells in the kidney cortex (66). In the clinic, biopsies from kidney transplant recipients on TAC therapy revealed increased apoptotic markers, such as caspase-3 activation and DNA fragmentation (64). These findings suggest that TAC-induced apoptosis contributes to the deterioration of kidney function in humans.

-

-

- Adverse Outcome: Kidney failure

-

Kidney biopsies taken from patients exposed to TAC and CsA revealed several clinical manifestations of nephrotoxicity. These include mild arteriolopathy, striped interstitial fibrosis, glomerular congestion, tubular microcalcification and arterial hyalinosis (69). Other than histological abnormalities, decline in kidney function is often observed in patients (70). Kidney function can be estimated by measuring serum creatinine levels. Creatinine is a waste product in the body that is freely filtered at a constant rate and minimally reabsorbed by the kidney. Using serum creatinine, the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) can be calculated with a formula that adjusts for age and sex. Kidney failure, e.g. end-stage kidney disease, is defined as an eGFR below 15 mL/min/1.73 m². Next to declined eGFR, other indicators for declined kidney function are decreases in urea clearance, leading to increased blood urea nitrogen (70). Urea is the end product of protein metabolism formed in the liver and is excreted, reabsorbed and transported by the kidneys. Studies have reported that 9.5% to 16.5% of patients develop kidney failure as a result of continuous CNI usage (71, 72).

Strategy

This adverse outcome pathway (AOP) is developed as part of the ‘Virtual Human for Safety Assessment (VHP4Safety)’ consortium. The mission of the consortium is to improve the prediction of the potential harmful effects of chemicals and pharmaceuticals based on a holistic, interdisciplinary definition of human health by developing the Virtual Human Platform and accelerating the transition from animal-based testing to innovative safety assessment. The Virtual Human Platform integrates data on human physiology, chemical characteristics and perturbations of biological pathways, for the first time in an inclusive and integrated manner. This project is funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) programme entitled the ’Dutch Research Agenda: Research on Routes by Consortia (NWA-ORC).

Within the VHP consortium, in vitro case studies are used to feed the Virtual Human Platform with newly generated data. This AOP focuses on nephrotoxicity caused by tacrolimus (TAC), cyclosporin A (CsA) and other calcineurin inhibitors leading to kidney failure.

Summary of the AOP

Events:

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE)

Key Events (KE)

Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|

| KE | 1172 | Increased activation, Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) | Increased activation, Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) |

| KE | 1174 | Activation, NADPH Oxidase | Activation, NADPH Oxidase |

| KE | 1115 | Increase, Reactive oxygen species | Increase, ROS |

| KE | 1392 | Increase, Oxidative Stress | Increase, Oxidative Stress |

| KE | 177 | Increase, Mitochondrial dysfunction | Increase, Mitochondrial dysfunction |

| KE | 2403 | Metabolic impairment | Metabolic impairment |

| KE | 1283 | Activation, TGF-beta pathway | Activation, TGF-beta pathway |

| KE | 2404 | Increase, kidney fibrosis | Increase, kidney fibrosis |

| KE | 1365 | Increase, Apoptosis | Increase, Apoptosis |

| AO | 759 | Increased, Kidney Failure | Increased, Kidney Failure |

Relationships Between Two Key Events (Including MIEs and AOs)

Network View

Prototypical Stressors

Life Stage Applicability

| Life stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Not Otherwise Specified |

Taxonomic Applicability

Sex Applicability

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Unspecific |

Overall Assessment of the AOP

In this section, we assessed the AOP using the Brasdford-Hill criteria (73), including the AOP’s biological plausibility and assessment of the empirical evidence: dose-response and temporal concordance. We also assessed the overall KEs within the AOP, including their domain of applicability and essenciality.

Biological Plausibility

Currently, there is no evidence supporting the intracellular transport of calcineurin inhibitors, specifically TAC and CsA. TAC has been documented to be secreted from proximal tubule cells in the kidney via the P-glycoprotein efflux pump, encoded by the ABCB1/MDR1 gene (74). However, it remains unclear whether this transport is exclusively mediated by P-glycoprotein or involves other transporters. This gap in knowledge regarding the cellular transport mechanisms of these agents presents a significant challenge in elucidating the initial triggering event and subsequent KEs and relationships (KERs). Although the MIE could not be identified, it has been suggested that NF-κB and NOX2 activation are among the earliest key events in nephrotoxicity induced by CNI (14, 16, 17). Exposure to these nephrotoxic agents results in increased expression of both NF-κB and NOX2. The activation of NF-κB and NOX2 promotes the generation of ROS by transferring an electron from NADPH to molecular oxygen within the mitochondrial respiratory chain.

In this AOP, although the sequence of KEs is depicted linearly, we propose that the KEs of ROS production, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction are fundamentally interconnected and dynamic processes that occur simultaneously. This simultaneity complicates the assessment of whether one event precedes another or if they occur concurrently. Given that critical metabolic processes occur in the mitochondria, mitochondrial dysfunction results in metabolic impairment (7). Studies have identified the metabolic pathways of arginine, amino acids, and pyrimidine as the most affected by TAC exposure in both in vitro and in vivo models (7). Metabolic impairment due to CNI exposure has been associated with aberrant TGF-β signaling and subsequent fibrosis in kidney cells and animal models (49). Evidence suggests that fibrosis may arise from either increased TGF-β levels or malfunctions in the TGF-β receptor signaling pathway, or a combination of both (49). Increased fibrosis has been observed alongside the presence of pro-apoptotic and apoptotic cells in in vitro, animal, and human studies (64, 75). However, apoptosis can be triggered by various stressors, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased fibrosis, complicating its placement within the AOP framework. Ultimately, increased apoptosis leads to the loss of functional kidney tissue and eventual kidney failure.

Empirical evidence: Dose-response and temporal concordance

CNI induced kidney damage in patients is associated with the dosage of CNI. A mean reduction in TAC dosage of 41% (range 11–89) led to a 86% (range 45–100) reduction in serum creatinine within 1–14 days (76). To decrease CNI usage, combining CNI with or switching to other immunosuppressive drugs seems to be able to partly restore kidney function. Switching from CNI to sirolimus for example led to an increase of 27% of eGFR (from 34 to 42 ml/min/1.73m2) in adult liver transplant recipients (77). Adding immunosuppressant mycophenolate mofetil to reduce CNI doses led to decreased serum creatinine levels from 2.63+/-0.39 to 1.74+/-0.34 mg/dl after one month and was maintained within a follow-up period of 4.8 years in adult liver transplant recipients (78). In the pediatric heart transplant population, improvement of kidney function after decreasing CNI by 50% and adding mycophenolate was also observed. At 1 year post-intervention, GFR was increased by 67% from 46.5 to 77.6mL/min/1.73 m2a nd remained stable during the mean follow-up of 26.3 months (79).

In animal models, male Sprague-Dawley rats dosed daily with CsA (2.5 or 25 mg/kg/day), TAC (0.6 or 6 mg/kg/day) for 1-28 days, a significant increase in blood urea nitrogen was observed in rats treated with CsA (high dose) or TAC (high dose) for 14 and 28 days (80). In another study, significant impairment of eGFR was seen in Sprague-Dawley rats treated with doses of CsA as low as 5 mg/kg/day (81). CsA 7.5 mg/kg/day caused a significant reduction in effective kidney plasma flow, and at 10 mg/kg/day filtration fraction declined significantly, again, implying that CNI-induced kidney failure is dose-dependent (81). In vitro models also showed that several KE’s in this AOP are dose-dependent. First of all, Jin et al. showed a dose-response in cell viability when HK-2 cells were exposed to TAC (82). Additionally, increased ROS production and acecelerated apoptosis were found in those cells in a dose-dependent manner. In human mesangial cells, CsA exposure led to a dose-dependent loss of viability, and only after 48 hours a decrease in cell proliferation was observed, suggesting that CsA nephrotoxicity is also time-dependent (83). In PTEC, the oxygen consumption rate and activity of the electron transport chain complexes I, II, IV were dose-dependently decreased after 48 hour exposure to CsA whereas glycolysis, measured by the extracellular acidification rate is dose-dependently increased, which both could be an indicator of mitochondrial dysfunction (84). In conclusion, aforementioned in vitro, in vivo and in clinical results imply that CNI treatment is associated with several KE’s and kidney failure in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

Domain of Applicability

Mechanistic evidence for KEs and KERs in this AOP primarily comes from rodent studies and immortalized kidney cell lines, and limited clinical evidence. Due to this, it remains unclear whether this AOP can be fully applied to other species and life stages. This AOP outlines the general mechanisms leading to kidney failure across various species, including humans and rodents.

Theoretically, this AOP could be applicable to all life stages and any organism capable of experiencing CNI-related kidney failure. There is an edivent limitation in empirical support, with very limited studies detailing the KEs and KERs. Additionally, there is limited information on the dose- and time-dependent response relationships for most of the stressors within this AOP, particularly in studies that measure the relationship between the KEs in the context of CNI exposure and the kidney. Therefore, additional quantitative data is needed before this AOP can be considered for regulatory significance.

Essentiality of the Key Events

|

MIE/KE |

Short name |

Support |

Essentiality |

|

MIE |

N/A |

Unidentified event |

N/A |

|

1 |

NF-κB and NOX2 activation |

NF-κB inhibition by affeic acid phenethyl ester suppressed NOX2 protein expression in both WT and CnAα−/− kidney fibroblasts, and significantly reduced ROS levels in CnAα−/− cells, indicating that NF-κB mediates CnAα-induced NOX2 regulation (14). Inhibition of NOX2 by coadministration of apocynin or diphenyleneiodonium in Fisher344 rats treated with CsA was associated with reduced striped fibrosis and cytoplasmic vacuolization that characterize chronic CNI toxicity (16). Additionally, treatment of wild-type and Nox2 null (B6.129S-CybbTm1Din/J) mice with high dose CsA revealed that in the KO mice significantly lower levels of α-SMA and 4-hydroxynonenal protein were found in the kidney, indicating that NOX2 is a mediator in chronic CNI toxicity. |

High |

|

2 |

ROS increase |

CTLA4-Ig, a fusion protein, can effectively reduce TAC-induced increase in ROS levels and oxidative stress in HK-cells. Additionally, in rats, CTLA4-Ig treatment significantly reversed kidney function indices induced by TAC, including blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, malondialdehyde, glutathione, 8-OHdG, 4-HHE, catalase, glutathione S-transferase and glutathione reductase(82). |

High |

|

3 |

Oxidative stress increase |

Treatment with coenzyme Q10 has been shown to reduce mitochondrial ROS production and alleviate TAC-induced dysfunction in the kidney by preventing apoptosis in HK-2 cells(31). Additionally, treatment with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4-immunoglobulin (CTLA4-Ig) has been reported to alleviate TAC induced oxidative stress and apoptotic cell death in HK-2 cells via the activation of the protein kinase B (AKT)/forkhead transcription factor (FOXO) 3 pathway (82). |

High |

|

4 |

Mitochondrial dysfunction |

HK-2 cells treated with TAC and coenzyme Q10, an antioxidant, had higher rates of basal mitochondrial respiration than those treated with TAC only, indicating an increased activity of mitochondria. Additionally, the cells treated with coenzyme Q10 also showed higher ATP-associated and total respiration (31). |

Low/Medium |

|

5 |

Metabolic impairment |

A study showed that CTLA4-Ig treatment in mice and HK-2 cells exposed to TAC significantly reversed the altered levels of several key metabolites, including blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, malondialdehyde, glutathione, 8-OHdG, 4-HHE, catalase, glutathione S-transferase, and glutathione reductase (82). |

Low/Medium |

|

6 |

Aberrant TGF-β |

In vitro studies using conditionally immortalized PTECs and in vivo studies have demonstrated that inhibition of TGF-β prevented TGF-β activation and consequent fibrosis signalling in the context of Cas exposure (56, 85).

|

Low/Medium |

|

7 |

Increased kidney fibrosis |

In vivo treatment with TGF-β in mice results in increased intra-renal osteopontin (OPN) mRNA and protein expression (85). In TAC-treated animals, a parallel increase in OPN and TGF-β mRNA was observed. Fibrosis inhibition by TGF-β blockage downregulated both TGF-β and OPN mRNA expression in PTECs, with similar results obtained in vivo with CsA-treated mice (86), leading to macrophage infiltration and consequent inflammation and fibrosis.

|

Low/Medium |

|

8 |

Apoptosis |

Treatment with coenzyme Q10 was shown to alleviate TAC-induced dysfunction in the kidney by preventing apoptosis in HK-2 proximal tubule cells (31). Additionally, cilastatin treatment acts as an anti-apoptotic agent in TAC-induced nephrotoxicity in proximal tubular cells and in rat models (87). |

High |

|

AO |

Kidney failure |

CNI treatment, including mostly TAC and CsA, has been associated with both acute and CKD due to its narrow therapeutic window (2, 3). Nephrotoxicity due to treatment with CNIs occurs often in solid-organ transplantation, including liver (52%), heart (20–75%) and kidney (76–94%) transplant recipients (4). |

High |

Evidence Assessment

The clinical evidence, linking nephrotoxicity caused by CNI to kidney failure, is strong and reliable. However, the mechanistic links between exposure to the agents and kidney failure remain poorly described and, therefore, not well understood. We were unable to find any evidence of a specific MIE, which thus remains unknown. The toxicity trigger of CNIs can be influenced by the kinetics of the individual stressors, which are determined by the transporters that these agents use to enter cells. Except for P-glycoprotein, neither influx nor efflux transporters have been identified, which hampers the identification of the MIE and the potential subsequent cascade of events. Currently, there are no reported alternative mechanisms that deviate from the proposed AOP, but additional contributors to the current AOP should not be excluded. This AOP is a qualitative description of the pathway and does currently not include quantitative information on dose-response relationships. However, it is known that CNI treatment needs frequent drug monitoring due to its narrow therapeutic window. There is substantial inter-individual variability in drug exposure, which may result from differences in metabolic enzymes (CYP3A4/5) and transporter polymorphisms (ABCB1), as well as the impact of high-fat meals that can reduce CNI absorption (88). These factors need to be considered when quantifying the AOP. There are limited studies available for each of the KEs and KERs to provide empirical support for this AOP, and there is a lack of substantial information on the dose-response relationships for the stressor agents. Additionally, no single study measures all reported KEs simultaneously following exposure to various doses, which hinders the ability to perform a highly accurate dose-response and concordance analysis. Extensive further research is needed to provide a better quantitative understanding of dose-response relationships between upstream and downstream KEs, as well as the elucidation of the MIE.

Known Modulating Factors

| Modulating Factor (MF) | Influence or Outcome | KER(s) involved |

|---|---|---|

Quantitative Understanding

The quantitave understanding of the KERs does not apply to this qualitative AOP. The Weight of Evidence (WoE) analysis revealed that many KERs lack considerable experimental proof, particularly in demonstrating the direct relationship with the proposed upstream and downstream KEs within individual studies. Therefore, this AOP should be considered as a qualitative contribution and as a backbone to build on in the future until quantitative data becomes available.

While some quantitative connections between upstream KEs have been identified in a few studies, the variability in the models used and the dosages chosen makes it difficult to compare studies and draw conclusions. Ideally, future efforts to strengthen WoE should focus on either gathering data from a single system type that shows exposure to a stressor correlating with changes observed in all described KEs or harmonizing the existing evidence in order to identify gaps to be filled and to further investigate.

Considerations for Potential Applications of the AOP (optional)

The AOP described here aims to provide a basic mechanistic framework for developing in vitro assays that could accurately predict quantitatively nephrotoxicity safety assessments. These assays could be part of an integrated testing strategy to minimize the need for repeated dose toxicity studies. Generating quantitative data by measuring all KEs in a single model after exposure to various concentrations of CNI could also accelerate the development of computational predictive methods. With potential overlap between KEs in this AOP with other nephrotoxic agents, the current AOP could offer additional connections for extensive networks to model nephrotoxicity and kidney failure.

References

- Reference list

1. Safarini OA, Keshavamurthy C, Patel P. Calcineurin Inhibitors. BTI - StatPearls.

2. Farouk SS, Rein JL. The Many Faces of Calcineurin Inhibitor Toxicity-What the FK? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27(1548-5609 (Electronic)):56-66.

3. Xia T, Zhu S, Wen Y, Gao S, Li M, Tao X, et al. Risk factors for calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity after renal transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12(1177-8881 (Electronic)):417-28.

4. Joy MS, Hogan SL, Thompson BD, Finn WF, Nickeleit V. Cytochrome P450 3A5 expression in the kidneys of patients with calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2007;22(7):1963-8.

5. Lim SW, Jin L, Piao SG, Chung BH, Yang CW. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV protects tacrolimus-induced kidney injury. Lab Invest. 2015;95(10):1174-85.

6. Xiao Z, Li C, Shan J, Luo L, Feng L, Lu J, et al. Mechanisms of renal cell apoptosis induced by cyclosporine A: a systematic review of in vitro studies. Am J Nephrol. 2011;33(6):558-66.

7. Aouad H, Faucher Q, Sauvage FL, Pinault E, Barrot CC, Arnion H, et al. A multi-omics investigation of tacrolimus off-target effects on a proximal tubule cell-line. Pharmacol Res. 2023;192:106794.

8. Rodrigues-Diez R, González-Guerrero C, Ocaña-Salceda C, Rodrigues-Diez RR, Egido J, Ortiz A, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine A and tacrolimus induce vascular inflammation and endothelial activation through TLR4 signaling. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27915.

9. Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-κB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18(49):6853-66.

10. Zhang Y-k, Sun X, Muraoka K-i, Ikeda A, Miyamoto S, Shimizu H, et al. Immunosuppressant FK506 Activates NF-κB through the Proteasome-mediated Degradation of IκBα: REQUIREMENT FOR IκBα N-TERMINAL PHOSPHORYLATION BUT NOT UBIQUITINATION SITES*. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(49):34657-62.

11. González-Guerrero C, Ocaña-Salceda C, Berzal S, Carrasco S, Fernández-Fernández B, Cannata-Ortiz P, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors recruit protein kinases JAK2 and JNK, TLR signaling and the UPR to activate NF-κB-mediated inflammatory responses in kidney tubular cells. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2013;272(3):825-41.

12. Tamada S, Nakatani T, Asai T, Tashiro K, Komiya T, Sumi T, et al. Inhibition of nuclear factor-κB activation by pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate prevents chronic FK506 nephropathy. Kidney International. 2003;63(1):306-14.

13. Abd-Eldayem AM, Makram SM, Messiha BAS, Abd-Elhafeez HH, Abdel-Reheim MA. Cyclosporine-induced kidney damage was halted by sitagliptin and hesperidin via increasing Nrf2 and suppressing TNF-α, NF-κB, and Bax. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1):7434.

14. Cheriyan AM, Ume AC, Francis CE, King KN, Linck VA, Bai Y, et al. Calcineurin A-α suppression drives nuclear factor-κB-mediated NADPH oxidase-2 upregulation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2021;320(5):F789-f98.

15. Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(1):245-313.

16. Djamali A, Reese S, Hafez O, Vidyasagar A, Jacobson L, Swain W, et al. Nox2 is a mediator of chronic CsA nephrotoxicity. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(8):1997-2007.

17. Djamali A, Wilson NA, Sadowski EA, Zha W, Niles D, Hafez O, et al. Nox2 and Cyclosporine-Induced Renal Hypoxia. Transplantation. 2016;100(6):1198-210.

18. Kidokoro K, Satoh M, Nagasu H, Sakuta T, Kuwabara A, Yorimitsu D, et al. Tacrolimus induces glomerular injury via endothelial dysfunction caused by reactive oxygen species and inflammatory change. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2012;35(6):549-57.

19. Kausar S, Wang F, Cui H. The Role of Mitochondria in Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Its Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells. 2018;7(12).

20. Tirichen H, Yaigoub H, Xu W, Wu C, Li R, Li Y. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Contribution in Chronic Kidney Disease Progression Through Oxidative Stress. Front Physiol. 2021;12:627837.

21. Gao P, Du X, Liu L, Xu H, Liu M, Guan X, et al. Astragaloside IV Alleviates Tacrolimus-Induced Chronic Nephrotoxicity via p62-Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway. (1663-9812 (Print)).

22. Kim JW, Nam SA, Seo E, Lee JY, Kim D, Ju JH, et al. Human kidney organoids model the tacrolimus nephrotoxicity and elucidate the role of autophagy. (2005-6648 (Electronic)).

23. de Arriba G, de Hornedo JP, Rubio SR, Fernandez MC, Martinez SB, Camarero MM, et al. Vitamin E protects against the mitochondrial damage caused by cyclosporin A in LLC-PK1 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;239(3):241-50.

24. Santel A, Fuller MT. Control of mitochondrial morphology by a human mitofusin. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(Pt 5):867-74.

25. Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Dal Zilio B, Scorrano L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(45):15927-32.

26. Youle RJ, Karbowski M. Mitochondrial fission in apoptosis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2005;6(8):657-63.

27. James DI, Martinou JC. Mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis: a painful separation. Dev Cell. 2008;15(3):341-3.

28. Rahal A, Kumar A, Singh V, Yadav B, Tiwari R, Chakraborty S, et al. Oxidative stress, prooxidants, and antioxidants: the interplay. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:761264.

29. Wijnen RM, Ericzon BG, Tiebosch AT, Buurman WA, Groth CG, Kootstra G. Toxicology of FK506 in the cynomolgus monkey: a clinical, biochemical, and histopathological study. Transpl Int. 1992;5 Suppl 1:S454-8.

30. Lim SW, Shin YJ, Luo K, Quan Y, Cui S, Ko EJ, et al. Ginseng increases Klotho expression by FoxO3-mediated manganese superoxide dismutase in a mouse model of tacrolimus-induced renal injury. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(15):5548-69.

31. Yu JH, Lim SW, Luo K, Cui S, Quan Y, Shin YJ, et al. Coenzyme Q10 alleviates tacrolimus-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in kidney. FASEB J. 2019;33(11):12288-98.

32. Gyurászová M, Gurecká R, Bábíčková J, Tóthová Ľ. Oxidative Stress in the Pathophysiology of Kidney Disease: Implications for Noninvasive Monitoring and Identification of Biomarkers. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:5478708.

33. Yu JH, Lim SW, Luo K, Cui S, Quan Y, Shin YJ, et al. Coenzyme Q. FASEB J. 2019;33(11):12288-98.

34. Oyouni AAA, Saggu S, Tousson E, Rehman H. Immunosuppressant drug tacrolimus induced mitochondrial nephrotoxicity, modified PCNA and Bcl-2 expression attenuated by. Toxicol Rep. 2018;5:687-94.

35. Durak I, Karabacak HI, Büyükkoçak S, Cimen MY, Kaçmaz M, Omeroglu E, et al. Impaired antioxidant defense system in the kidney tissues from rabbits treated with cyclosporine. Protective effects of vitamins E and C. Nephron. 1998;78(2):207-11.

36. M K K, John CM, Jonnagaladda B, Kesavan A, Arockiasamy S. Attenuation of tacrolimus induced oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and cell cycle arrest by. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2021;24(8):1087-97.

37. Ammar M, Yaich S, Hakim A, Ghozzi H, Sahnoun Z, Ben Hmida M, et al. Tacrolimus trough level and oxidative stress in Tunisian kidney transplanted patients. Ren Fail. 2024;46(1):2313863.

38. Joncquel M, Labasque J, Demaret J, Bout MA, Hamroun A, Hennart B, et al. Targeted Metabolomics Analysis Suggests That Tacrolimus Alters Protection against Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(7).

39. Forbes JM. Mitochondria-Power Players in Kidney Function? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27(7):441-2.

40. Kim JW, Nam SA, Seo E, Lee JY, Kim D, Ju JH, et al. Human kidney organoids model the tacrolimus nephrotoxicity and elucidate the role of autophagy. Korean J Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1420-36.

41. Nash A, Samoylova M, Leuthner T, Zhu M, Lin L, Meyer JN, et al. Effects of Immunosuppressive Medications on Mitochondrial Function. J Surg Res. 2020;249:50-7.

42. Nishida S, Ishima T, Kimura N, Iwami D, Nagai R, Imai Y, et al. Metabolomic Profiling of Mice with Tacrolimus-Induced Nephrotoxicity: Carnitine Deficiency in Renal Tissue. Biomedicines. 2024;12(3).

43. van Schaik M, Bredewold OW, Priester M, Michels WM, Rabelink TJ, Rotmans JI, et al. Long-term renal and cardiovascular risks of tacrolimus in patients with lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2024;39(12):2048-57.

44. Bhatia D, Capili A, Choi ME. Mitochondrial dysfunction in kidney injury, inflammation, and disease: Potential therapeutic approaches. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2020;39(3):244-58.

45. Xie D, Guo J, Dang R, Li Y, Si Q, Han W, et al. The effect of tacrolimus-induced toxicity on metabolic profiling in target tissues of mice. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2022;23(1):87.

46. Arnold PK, Finley LWS. Regulation and function of the mammalian tricarboxylic acid cycle. J Biol Chem. 2023;299(2):102838.

47. Choi I, Son H, Baek JH. Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle Intermediates: Regulators of Immune Responses. Life (Basel). 2021;11(1).

48. Sousa JS, D'Imprima E, Vonck J. Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Complexes. Subcell Biochem. 2018;87:167-227.

49. Kern G, Mair SM, Noppert SJ, Jennings P, Schramek H, Rudnicki M, et al. Tacrolimus increases Nox4 expression in human renal fibroblasts and induces fibrosis-related genes by aberrant TGF-βeta receptor signalling. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96377.

50. Gijsen VM, Madadi P, Dube MP, Hesselink DA, Koren G, de Wildt SN. Tacrolimus-induced nephrotoxicity and genetic variability: a review. Ann Transplant. 2012;17(2):111-21.

51. Thölking G, Fortmann C, Koch R, Gerth HU, Pabst D, Pavenstädt H, et al. The tacrolimus metabolism rate influences renal function after kidney transplantation. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111128.

52. Li Z, Sun F, Zhang Y, Chen H, He N, Song P, et al. Tacrolimus Induces Insulin Resistance and Increases the Glucose Absorption in the Jejunum: A Potential Mechanism of the Diabetogenic Effects. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0143405.

53. Khanna A, Plummer M, Bromberek C, Bresnahan B, Hariharan S. Expression of TGF-βeta and fibrogenic genes in transplant recipients with tacrolimus and cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int. 2002;62(6):2257-63.

54. Bennett J, Cassidy H, Slattery C, Ryan MP, McMorrow T. Tacrolimus Modulates TGF-β Signaling to Induce Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Renal Proximal Tubule Epithelial Cells. J Clin Med. 2016;5(5).

55. Ume AC, Wenegieme TY, Shelby JN, Paul-Onyia CDB, Waite AMJ, Kamau JK, et al. Tacrolimus induces fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition via a TGF-β-dependent mechanism to contribute to renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2023;324(5):F433-F45.

56. Ling H, Li X, Jha S, Wang W, Karetskaya L, Pratt B, et al. Therapeutic role of TGF-βeta-neutralizing antibody in mouse cyclosporin A nephropathy: morphologic improvement associated with functional preservation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(2):377-88.

57. Ninova D, Covarrubias M, Rea DJ, Park WD, Grande JP, Stegall MD. Acute nephrotoxicity of tacrolimus and sirolimus in renal isografts: differential intragraft expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 and alpha-smooth muscle actin. Transplantation. 2004;78(3):338-44.

58. Shihab FS, Yi H, Bennett WM, Andoh TF. Effect of nitric oxide modulation on TGF-βeta1 and matrix proteins in chronic cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int. 2000;58(3):1174-85.

59. Vieira JM, Noronha IL, Malheiros DM, Burdmann EA. Cyclosporine-induced interstitial fibrosis and arteriolar TGF-βeta expression with preserved renal blood flow. Transplantation. 1999;68(11):1746-53.

60. Wynn TA, Barron L. Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(3):245-57.

61. Mazzali M, Hughes J, Dantas M, Liaw L, Steitz S, Alpers CE, et al. Effects of cyclosporine in osteopontin null mice. Kidney Int. 2002;62(1):78-85.

62. Khanna A. Tacrolimus and cyclosporinein vitro and in vivo induce osteopontin mRNA and protein expression in renal tissues. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2005;101(4):e119-26.

63. Khanna AK, Cairns VR, Becker CG, Hosenpud JD. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta mimics and anti-TGF-βeta antibody abrogates the in vivo effects of cyclosporine: demonstration of a direct role of TGF-βeta in immunosuppression and nephrotoxicity of cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1999;67(6):882-9.

64. Thomas SE, Andoh TF, Pichler RH, Shankland SJ, Couser WG, Bennett WM, et al. Accelerated apoptosis characterizes cyclosporine-associated interstitial fibrosis. Kidney Int. 1998;53(4):897-908.

65. Lim BJ, Kim PK, Hong SW, Jeong HJ. Osteopontin expression and microvascular injury in cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19(3):288-94.

66. Choi SJ, You HS, Chung SY. Tacrolimus-induced apoptotic signal transduction pathway. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(8):2734-6.

67. Morse E, Schroth J, You Y-H, Pizzo DP, Okada S, RamachandraRao S, et al. TRB3 is stimulated in diabetic kidneys, regulated by the ER stress marker CHOP, and is a suppressor of podocyte MCP-1. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2010;299(5):F965-F72.

68. Kim R, Emi M, Tanabe K, Murakami S. Role of the unfolded protein response in cell death. Apoptosis. 2006;11(1):5-13.

69. Nankivell BJ, P'Ng CH, O'Connell PJ, Chapman JR. Calcineurin Inhibitor Nephrotoxicity Through the Lens of Longitudinal Histology: Comparison of Cyclosporine and Tacrolimus Eras. Transplantation. 2016;100(8):1723-31.

70. Laskow DA, Curtis Jj Fau - Luke RG, Luke Rg Fau - Julian BA, Julian Ba Fau - Jones P, Jones P Fau - Deierhoi MH, Deierhoi Mh Fau - Barber WH, et al. Cyclosporine-induced changes in glomerular filtration rate and urea excretion. (0002-9343 (Print)).

71. Ojo AO, Held PJ, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Leichtman AB, Young EW, et al. Chronic renal failure after transplantation of a nonrenal organ. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):931-40.

72. Gonwa TA, Mai ML, Melton LB, Hays SR, Goldstein RM, Levy MF, et al. END-STAGE RENAL DISEASE (ESRD) AFTER ORTHOTOPIC LIVER TRANSPLANTATION (OLTX) USING CALCINEURIN-BASED IMMUNOTHERAPY1: Risk of Development and Treatment. Transplantation. 2001;72(12).

73. Becker RA, Ankley GT, Edwards SW, Kennedy SW, Linkov I, Meek B, et al. Increasing Scientific Confidence in Adverse Outcome Pathways: Application of Tailored Bradford-Hill Considerations for Evaluating Weight of Evidence. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;72(3):514-37.

74. Udomkarnjananun S, Francke MI, Dieterich M, van De Velde D, Litjens NHR, Boer K, et al. P-glycoprotein, FK-binding Protein-12, and the Intracellular Tacrolimus Concentration in T-lymphocytes and Monocytes of Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2023;107(2):382-91.

75. Shulman H, Striker G, Deeg HJ, Kennedy M, Storb R, Thomas ED. Nephrotoxicity of cyclosporin A after allogeneic marrow transplantation: glomerular thromboses and tubular injury. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(23):1392-5.

76. Katari SR, Magnone M Fau - Shapiro R, Shapiro R Fau - Jordan M, Jordan M Fau - Scantlebury V, Scantlebury V Fau - Vivas C, Vivas C Fau - Gritsch A, et al. Clinical features of acute reversible tacrolimus (FK 506) nephrotoxicity in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 1997;11(0902-0063 (Print)):237-42.

77. Fairbanks KD, Eustace JA, Fine D, Thuluvath PJ. Renal function improves in liver transplant recipients when switched from a calcineurin inhibitor to sirolimus. Liver Transpl. 2003;9(10):1079-85.

78. Koch RO, Graziadei IW, Schulz F, Nachbaur K, Konigsrainer A, Margreiter R, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of mycophenolate mofetil in liver transplant recipients with calcineurin inhibitor-induced renal dysfunction. Transpl Int. 2004;17(9):518-24.

79. Boyer O, Le Bidois J, Dechaux M, Gubler MC, Niaudet P. Improvement of renal function in pediatric heart transplant recipients treated with low-dose calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 2005;79(10):1405-10.

80. Cui Y, Huang Q Fau - Auman JT, Auman Jt Fau - Knight B, Knight B Fau - Jin X, Jin X Fau - Blanchard KT, Blanchard Kt Fau - Chou J, et al. Genomic-derived markers for early detection of calcineurin inhibitor immunosuppressant-mediated nephrotoxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2011;124(1096-0929 (Electronic)):23-34.

81. Ferguson CJ, von Ruhland C Fau - Parry-Jones DJ, Parry-Jones Dj Fau - Griffiths DF, Griffiths Df Fau - Salaman JR, Salaman Jr Fau - Williams JD, Williams JD. Low-dose cyclosporin nephrotoxicity in the rat. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8(0931-0509 (Print)):1259-63.

82. Jin L, Shen N, Wen X, Wang W, Lim SW, Yang CW. CTLA4-Ig protects tacrolimus-induced oxidative stress via inhibiting the AKT/FOXO3 signaling pathway in rats. Korean J Intern Med. 2023;38(2005-6648 (Electronic)):393-405.

83. O'Connell S, Tuite N Fau - Slattery C, Slattery C Fau - Ryan MP, Ryan Mp Fau - McMorrow T, McMorrow T. Cyclosporine A--induced oxidative stress in human renal mesangial cells: a role for ERK 1/2 MAPK signaling. Toxicol Sci. 2012;126(1096-0929 (Electronic)):101-13.

84. Zmijewska AA, Zmijewski JW, Becker Jr EJ, Benavides GA, Darley-Usmar V, Mannon RB. Bioenergetic maladaptation and release of HMGB1 in calcineurin inhibitor-mediated nephrotoxicity. American Journal of Transplantation. 2021;21(9):2964-77.

85. Hong SW, Isono M Fau - Chen S, Chen S Fau - Iglesias-De La Cruz MC, Iglesias-De La Cruz Mc Fau - Han DC, Han Dc Fau - Ziyadeh FN, Ziyadeh FN. Increased glomerular and tubular expression of transforming growth factor-beta1, its type II receptor, and activation of the Smad signaling pathway in the db/db mouse. Am J Pathol. 2001;158(0002-9440 (Print)):1653-63.

86. Khanna AK, Cairns Vr Fau - Becker CG, Becker Cg Fau - Hosenpud JD, Hosenpud JD. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta mimics and anti-TGF-βeta antibody abrogates the in vivo effects of cyclosporine: demonstration of a direct role of TGF-βeta in immunosuppression and nephrotoxicity of cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1999;67(0041-1337 (Print)):882-9.

87. Luo K, Lim SW, Jin J, Jin L, Gil HW, Im DS, et al. Cilastatin protects against tacrolimus-induced nephrotoxicity via anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic properties. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):221.

88. Thongprayoon C, Hansrivijit P, Kovvuru K, Kanduri SR, Bathini T, Pivovarova A, et al. Impacts of High Intra- and Inter-Individual Variability in Tacrolimus Pharmacokinetics and Fast Tacrolimus Metabolism on Outcomes of Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. J Clin Med. 2020;9(7).

89. Josephine A, Amudha G, Veena CK, Preetha SP, Rajeswari A, Varalakshmi P. Beneficial effects of sulfated polysaccharides from Sargassum wightii against mitochondrial alterations induced by Cyclosporine A in rat kidney. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(11):1413-22.

90. de Arriba G, Calvino M, Benito S, Parra T. Cyclosporine A-induced apoptosis in renal tubular cells is related to oxidative damage and mitochondrial fission. Toxicology Letters. 2013;218(1):30-8.

91. El-Zoghby ZM, Stegall MD, Lager DJ, Kremers WK, Amer H, Gloor JM, et al. Identifying Specific Causes of Kidney Allograft Loss. American Journal of Transplantation. 2009;9(3):527-35.

92. Schwarz A, Haller H, Schmitt R, Schiffer M, Koenecke C, Strassburg C, et al. Biopsy‐Diagnosed Renal Disease in Patients After Transplantation of Other Organs and Tissues. American Journal of Transplantation. 2010;10(9):2017-25.