This AOP is licensed under the BY-SA license. This license allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms.

AOP: 346

Title

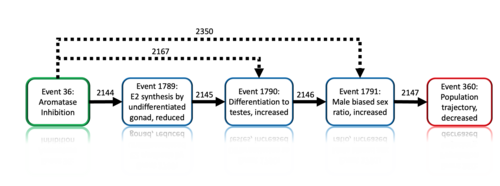

Aromatase inhibition leads to male-biased sex ratio via impacts on gonad differentiation

Short name

Graphical Representation

Point of Contact

Contributors

- Kelvin Santana Rodriguez

- Dan Villeneuve

- Gerald Ankley

Coaches

OECD Information Table

| OECD Project # | OECD Status | Reviewer's Reports | Journal-format Article | OECD iLibrary Published Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.12 | WPHA/WNT Endorsed | Scientific Review | Journal link | iLibrary link |

This AOP was last modified on October 17, 2023 04:51

Revision dates for related pages

| Page | Revision Date/Time |

|---|---|

| Inhibition, Aromatase | April 14, 2025 10:42 |

| Reduction, 17beta-estradiol synthesis by the undifferentiated gonad | July 13, 2022 10:25 |

| Increased, Differentiation to Testis | December 28, 2022 10:15 |

| Increased, Male Biased Sex Ratio | January 03, 2023 08:22 |

| Decrease, Population growth rate | January 03, 2023 09:09 |

| Inhibition, Aromatase leads to Increased, Differentiation to Testis | December 28, 2022 15:28 |

| Inhibition, Aromatase leads to Reduction, E2 Synthesis by the undifferentiated gonad | July 11, 2022 14:23 |

| Inhibition, Aromatase leads to Increased, Male Biased Sex Ratio | January 10, 2023 11:55 |

| Reduction, E2 Synthesis by the undifferentiated gonad leads to Increased, Differentiation to Testis | July 11, 2022 15:17 |

| Increased, Differentiation to Testis leads to Increased, Male Biased Sex Ratio | January 03, 2023 08:35 |

| Increased, Male Biased Sex Ratio leads to Decrease, Population growth rate | January 03, 2023 08:37 |

| Fadrozole | November 29, 2016 18:42 |

| Letrozole | November 29, 2016 18:42 |

| Exemestane | November 12, 2020 01:53 |

| Stressor:292 Clotrimazole | November 12, 2020 01:55 |

| Prochloraz | November 29, 2016 18:42 |

Abstract

This adverse outcome pathway links inhibition of aromatase activity in teleost fish during gonadogenesis to increased differentiation to testis resulting in a male-biased sex ratio in the population, and ultimately, reduced population sustainability. Most gonochoristic fish species develop either as males or females and do not change sex throughout their life span. However, in species where sexual differentiation is controlled at least to some degree by environmental factors, there can be a window of development during gonadal differentiation that is sensitive to a variety of exogenous conditions, including exposure to some chemicals. For example, treatment with sex steroids in conjunction with the period of sexual differentiation has been showed to favor ovary or testis development in fish exposed to estrogens or androgens, respectively. Altered synthesis and regulation of endogenous steroids can also affect sexual differentiation in fish. In most vertebrate taxa, aromatase (cytochrome P450 [CYP]19a1) is the rate-limiting enzyme for the conversion of 17β-estradiol (E2) from testosterone (T). Endocrine-active chemicals such as fadrozole, letrozole and exemestane (pharmaceuticals) or prochloraz and propiconazole (fungicides) inhibit aromatase activity. Exposure of some fish species to aromatase inhibitors during sex differentiation can reduce endogenous E2 synthesis, thereby resulting in phenotypic males, the default sex in the absence of estrogen signaling during gonadal differentiation. Given the critical role of female fecundity in determining total numbers of offspring, the resultant male-biased sex ratio can reduce population size, especially if sustained over multiple generations.

AOP Development Strategy

Context

In fish sexual differentiation occurs post hatch and can be influenced by exogenous factors such as chemicals, temperature, pH, population density, social cues and more. As a result, the gonadal sex phenotype in oviparous fish can be altered by environmental conditions experienced during development, particularly in conjunction with sexual differentiation (Scholz and Klüver, 2009). At this stage, the bipotential gonad can differentiate to either testes or ovaries depending both on genetic and environmental factors (Strüssmann and Nakamura, 2002). Sex steroids are among the factors that influence sex differentiation in non-mammalian vertebrates; in many fish species exogenous androgens and estrogens act, respectively, to enhance the development of testes and ovaries in exposed animals (Nakamura 2010). In teleost fish, the relative balance between endogenous estrogens and androgens during sexual differentiation is critical to ensuring normal sex ratios and, ultimately, viable populations. Various homeostatic mechanisms ensure that steroid biosynthesis is appropriately controlled during development. A key biosynthetic enzyme is CYP19a1 (aromatase), which is responsible for the conversion of C19 androgens (e.g., T) to C18 estrogens (e.g., E2) in brain and gonadal tissues of vertebrates (Payne and Hales, 2004; Simpson et al. 1994). In fish, there are two CYP19a1 isoforms, with CYP19a1a mostly expressed in the gonads and CYP19a1b largely expressed in the brain (Callard et al. 2001).

Since the mid-90s, there has been concern about the potential impacts of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in fish and wildlife. Many EDCs can exert effects in early life stages that can lead to potential impacts at the population level. For example, some chemicals have been shown to alter the sexual phenotype of fish by affecting steroidogenic enzymes such as aromatase. Inhibition of CYP19a1 expression or activity can alter the production of estrogens in developing gonads, affecting processes such as gonadal differentiation. In many fish species the “default” gonad type is testes, so when estrogen signaling is reduced there is a resultant bias toward male-biased sex ratios (Guiguen et al. 2010). When male biased sex ratios occur, the number of breeding females can decrease over time and have negative impacts on population growth and sustainability. The present AOP provides the evidence framework of the negative impacts of aromatase inhibition at early developmental stages of teleost fish during the critical period of sexual differentiation and how this could lead to population-level effects.

Strategy

Work on this AOP initially was conducted by Mr. Santana-Rodriguez under the supervision of Dr. Daniel Villeneuve, a leader in the field of AOP development. Dr. Gerald Ankley also contributed to AOP development, particularly at later stages of the effort. Dr. Ankley is experienced with AOP development, and is a widely-recognized international expert concerning the effects of EDCs on fish. The AOP is based on published peer-reviewed literature derived from focused searches guided by the expertise of the authors. Ms. Kathleen Jensen, who also has worked for many years on EDCs/fish endocrinology, provided a secondary QA review of key papers supporting the AOP.

Summary of the AOP

Events:

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE)

Key Events (KE)

Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|

| MIE | 36 | Inhibition, Aromatase | Inhibition, Aromatase |

| KE | 1789 | Reduction, 17beta-estradiol synthesis by the undifferentiated gonad | Reduction, E2 Synthesis by the undifferentiated gonad |

| KE | 1790 | Increased, Differentiation to Testis | Increased, Differentiation to Testis |

| KE | 1791 | Increased, Male Biased Sex Ratio | Increased, Male Biased Sex Ratio |

| AO | 360 | Decrease, Population growth rate | Decrease, Population growth rate |

Relationships Between Two Key Events (Including MIEs and AOs)

| Title | Adjacency | Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|

| Inhibition, Aromatase leads to Increased, Differentiation to Testis | non-adjacent | High | |

| Inhibition, Aromatase leads to Increased, Male Biased Sex Ratio | non-adjacent | Moderate |

Network View

Prototypical Stressors

Life Stage Applicability

| Life stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Development | High |

Taxonomic Applicability

Sex Applicability

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Unspecific | High |

Overall Assessment of the AOP

See details below.

Domain of Applicability

Life Stage

The life stage to which this AOP applies is developing embryos/juveniles during gonadal differentiation. Since the sexually dimorphic expression of aromatase has been shown to play a crucial role in the differentiation to testis vs ovary of the undifferentiated bipotential gonad (Guiguen et al. 2010), the AOP is applicable to the stage of development during which aromatase might influence this process. The precise timing of the sensitive period relevant to this AOP will vary by species, but the AOP is not applicable to differentiated juveniles or to adults.

Studies with zebrafish (Danio rerio) have shown that both brain and gonadal aromatase expression can be observed at 20 days post-fertilization (dpf) with an increase in expression at 25 dpf in fish destined to become females, coinciding with the onset of gonadal differentiation period (Lau et al. 2016). In Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), aromatase expression can be observed as early as 3-4 dpf with an increase in expression starting at 11 dpf in genetic females (Kwon et al. 2001). Additionally, it has been shown that the period of 7-14 dpf is the most sensitive to chemical inhibition of CYP19a1 activity, and a continuous exposure of 2-3 weeks is sufficient for the masculinization of the majority of genetic female tilapia (Kwon et al. 2000). This clearly indicates alteration of differentiation from ovary to testis results during sex differentiation (OECD 2011).

Sex

The molecular initiating event for this AOP occurs during gonad differentiation. Therefore, the AOP is only applicable to sexually undifferentiated individuals.

Taxonomic

Most evidence for the taxonomic applicability of this AOP comes from species in the class Osteichthyes. Aromatase itself is well conserved among vertebrates (e.g., Wilson et al. 2005; LaLone et al. 2018). However, the degree to which aromatase and subsequent production of endogenous estrogens such as E2 are involved in sex determination or sexual differentiation varies with species. Many fish, amphibian, and reptile species have environmental sex determination, and regulation of aromatase expression and sex steroids profiles are closely tied to sex-determining environmental factors (Angelopoulou et al. 2012). Alternatively, vertebrates that largely rely on genetic sex determination (birds, mammals) would be anticipated to be less vulnerable to effects of aromatase inhibitors during gonad differentiation, although there remains compelling evidence for an important role of steroid signaling during the process (Angelopoulou et al. 2012). Overall, regardless of differing roles for aromatase in sexual differentiation, expression appears universal among vertebrates during this life stage (Angelopoulou et al. 2012; Sarre et al. 2004; Uller and Helantera, 2011; Ramsey and Crews, 2009). Thus, in principle, components of the present AOP may have some degree of applicability to all vertebrates. Given the substantial diversity of sex determination and differentiation strategies in fish, amphibians and reptiles (including those from closely related phylogenetic groups; Sarre et al. 2004; Angelopoulou et al. 2012), quantiative sensitivity, and taxonomic domain of appicability of the present AOP are hard to generalize, although there is reason to believe it should have broad applicability in bony fishes.

Essentiality of the Key Events

Direct support for the essentiality of several of the key events in the AOP has been provided by gene modification/knockout studies of the cyp19a1 gene in zebrafish and Nile tilapia. Specifically:

- Lau et al. (2016) generated insertion/deletion mutations in the zebrafish cyp19a1a gene using TALEN (transcription activator-like effector nuclease) and CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)/Cas9 approaches. All mutant cyp19a1a-/- fish developed as males. Histological examination (at 120 dpf) of the cyp1a1a-/- mutants showed that they exhibited normal spermatogenesis in the testis with no observable difference between the wild type (+/+) and heterozygous (+/-) males. To confirm the necessity of E2 synthesis for ovarian differentiation, they performed an experiment to "rescue" the phenotype of cyp19a1a mutants by E2 treatment (0.05, 0.50 and 5.00 nM) encampassing the period of gonadal differentiation (15–30 days pdf). Treatment with the estrogen resulted in normal functioning ovaries with fully developed perinucleolar oocytes and small amount of stromal tissue, even in some individuals at the lowest E2 concentration (0.05 nM). This supports the essentiality of aromatase inhibition relative to E2 synthesis reduction as a critical step for testis differentiation.

- In a similar study also with zebrafish, Muth-Köhne et al. (2016) generated cyp19a1a and cyp19a1b gene mutant lines and a cyp19a1a;cyp19a1b double-knockout line using TALENs. All cyp19a1a mutants and cyp19a1a;cyp19a1b double mutants developed as males, whereas cyp1a1b double mutant (-/-) had a 1:1 sex ratio similar to the wild type controls. This again supports the essentiality of gonadal aromatase inhibition for testis differentiation that would lead to a male biased sex ratio. Additionally, a small rescue experiment performed using E2 on all male mutant cyp1a1a-/- indicated that E2 treatment could restore a near normal sex ratio (9 females among 14 fish).

- Studies in Nile tilapia similar to those conducted in zebrafish were described by Zhang et al. (2017), who worked with genetic female mutants for cypa19a and cyp19a1b. Results showed that all cyp19a1a+/- XX and cyp19a1a+/+ XX fish developed as females, whereas all cyp19a1a-/- XX and cyp19a1a-/- XY fish developed as males, based on gonad differentiation. The cyp19a1a-/- XX tilapia shifted to the male pathway as early as 5 dph and ultimately were fertile. This again provides strong support for the critical role of gonadal aromatase relative to ovarian development.

|

Key Event |

Evidence |

Essentiality/Assessment |

|

Inhibition, Aromatase |

strong |

There is good evidence from gene knockout experiments of the two different isoforms of aromatase that support the specificity of gonadal aromatase inhibition for the subsequent key events to occur. |

|

E2 Synthesis by the undifferentiated gonad |

weak |

There is evidence from a stop (by cyp19a1 knockout) and recovery (through compensation) experiment where E2 can rescue the sex ratio altered due to the gonadal aromatase gene knockout suggesting that E2 depletion is necessary for the subsequent key events to occur. |

|

Differentiation to Testis |

strong |

By definition, differentiation to testis is required for a male reproductive phenotype. |

|

Male Biased Sex Ratio |

moderate |

Breeding females (and both sexes) are necessary for population sustainability. A male biased sex population suggests a reduced offspring production and consequentially reduced population sustainability. |

|

Population Sustainability |

n/a |

This is the terminal key event in the AOP. Its essentiality for progression to downstream events in the sequence cannot be evaluated. |

Evidence Assessment

Biological Plausibility

Aromatase catalyzes the conversion of T to E2, so the biological plausibility of aromatase inhibition leading to reductions in available E2 is clear. Additionally, the role of E2 as a major regulator of normal female gonad development is well documented (Gorelick et al. 2011; Guiguen et al. 2010). The link between E2 reductions leading to increased differentiation of the bipotential gonad to testis is highly plausible. As E2 signaling is reduced, ER responsive genes required for ovarian differentiation will be downregulated in the bipotential gonad resulting in a default development of testes (Yin et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2017). Therefore, it is plausible that E2 reduction in the undifferentiated gonad at the onset of sexual differentiation would promote testis formation. The direct link between increased differentiation to testis leading to a male biased sex ratio is also well supported by biological plausibility. If the conditions that favor a male producing phenotype (in this case, the aromatase inhibitor) overlap with the critical period of sex differentiation in a given population, it is reasonable that relatively more male offspring will be produced (D'Cotta et al., 2001, Kwon et al., 2000; Luzio et al. 2016). Therefore, exposure of sensitive species to aromatase inhibition for an extended period of time during reproducitve development plausibly would result in a male-biased population. Empirical evidence supporting the direct link between male biased cohorts and a reduced population sustainability in fish species is limited. However, biased sex ratios can definitely impact fish populations (Marty et al. 2017). For example, a male-biased sex ratio would logically lead to a reduction in the number of breeding females such that over time decreases in offspring would result in population declines (Brown et al. 2015; Grayson et al. 2014). Miller et al. (2022) recently developed a model specifically designed to capture the effects of male-biased sex ratios on population trajectories in fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas).

Concordance of Dose Response Relationships

There have been a number of in vitro and in vivo studies, primarily in fish, that have examined the effects of known aromatase inhibitors on different key events in the AOP. Most of these studies only measured one key event in the AOP so cannot be directly used to explore dose-response concordance between key events.

The differential sensitivity to inhibition of aromatase is most easily measured in vitro. Doering et al. (2019b) determined the effects of different concentrations of several known aromatase inhibitors (e.g., fadrozole, prochloraz) on brain aromatase activity in a taxonomically-diverse set of fish species, and found that while absolute potency of the chemicals varied across species, rank order potency of the test chemicals was generally similar. Importantly, relative potencies measured in vitro reflected those observed in in vivo studies such as those described below, thus providing indirect evidence of dose concordance between the MIE and downstream Key Events.

There have been several in vivo studies evaluating the effects of varying degrees of aromatase inhibition on different key events in the AOP. However, there are limitations to these studies in the context of determining dose-dependency across all key events in the AOP. For example, E2 levels typically have not been or measured or determined at a time relevant to gonadal differentiation. However, a few have measured multiple key events, although typically only at one time point. One study assessed dose-reponse relationships between different concentrations of the model aromatase inhibitor exemestane and expression of the enzyme. Immunohistochemical analyses revealed that gonad tissue of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) exposed from 9-35 days post-hatch (dph) to 100, 500, 1000 and 2000 μg/g feed had no cross-reaction with P450arom at the three highest doses, but gonad tissue samples exhibited a strong immunopositive responses against P450arom at a lower dose of exemestane (100 μg/g feed), similar to the differentiating ovaries of the control fish (Ruksana et al. 2010). No ovarian development was noted in fish in the 500, 1000 and 2000 mg/kg treatments, and the 1000 and 2000 treatments resulted in 100% phenotypic males.

Uchida et al. (2004) evaluated two key events in the AOP in an experiment with fadrozole using zebrafish genetic females exposed from 15-40 dph via the diet. They observed ovarian transition to testis in all exposed animals, culminating in 62.5, 100 and 100% males in 10, 100 and 1000 mg/kg treatments, respectively.

Another study showed a dose-dependent rate of increased differentiation to testes in zebrafish exposed from 0-63 dph to different concentrations of fadrozole (10, 32, 100 ug/L) via the water (Muth-Köhne et al. 2016).

The most commonly reported dose response relationship for this AOP was for the non-adjacent relationship between aromatase inhibition and an increased male biased sex ratio. For example, Nile tilapia, zebrafish, fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas), bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) and Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) exposed to different concentrations of known aromatase inhibitors (exemestane, fadrozole, letrozole, prochloraz) via the diet or water reported dose-dependent increases in the relative number of males (Kwon et al. 2000; Kitano et al. 2000; Thorpe et al. 2011; Holbech et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2010; Shen et al. 2013).

Finally, there are models that demonstrate a dose-dependent decrease in population size corresponding with an increasing proportion of males in zebrafish and fathead minnows (Brown et al. 2015; Miller et al. 2022).

Temporal Concordance

Because this AOP involves actions during a specific development transition from an undifferentiated to differentiated gonad, the temporal concordance of the events is implicit. A male biased sex ratio cannot be observed until the population has undergone sexual differentiation. Likewise, reproduction and associated population growth rate cannot be assessed until the animals achieve sexual maturity.

Consistency

There have been a number of in vitro and in vivo studies, primarily in fish, that have examined the effects of known aromatase inhibitors on different key events in the AOP. Some of these studies measured only one key event in the AOP and/or employed just a single dose of a given stressor, so cannot be directly used to explore dose-response concordance. However, even with these limitations, they demonstrate that the overall AOP is consistent with expectations in a variety of species exposed to known chemical inhibitors of aromatase (see Dose Concordance table). For example, studies with chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), Japanese fugu (Takifugu rubripes), Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes), Nile tilapia, zebrafish, fathead minnow, bluegill, yellow catfish and Japanese flounder exposed to known aromatase inhibitors (exemestane, fadrozole, letrozole, prochloraz) via the diet or water during sexual differentiation have reported increases in differentiation to testis and/or the relative number of males (Piferrer et al. 1994; Kwon et al. 2000; Rashid et al. 2007; Kitano et al. 2000; Thorpe et al. 2011; Thresher et al. 2011; Holbech et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2010; Shen et al. 2013).

Male-biased sex ratios are not specific to this AOP. Many of the key events included overlap with another AOP (#376) linking activation of the androgen receptor to male biased sex ratios.

Uncertainties, inconsistencies, and data gaps

Currently the major uncertainty in this AOP is the biological linkage between E2 synthesis reduction by the undifferentiated gonad leading to an increased, differentiation to testis. Biological plausibility connections have been established, but experimental measurements of E2 during the particular period of differentiation are lacking. Also, as noted in the Domain of Applicability section, the taxonomic range of applicability of the AOP is uncertain.

Known Modulating Factors

| Modulating Factor (MF) | Influence or Outcome | KER(s) involved |

|---|---|---|

Quantitative Understanding

There is not yet a sufficient quantitative understanding of this overall AOP to predict the degree to which aromatase inhibition would result in population-level impacts. That said, there are models available suitable for the quantitative prediction of changes in E2 levels caused by degree of aromatase inhibition in some small fish species (Conolly et al. 2018; Doering et al. 2019a), as well as the effects of different (male-biased) sex ratios on fathead minnow population size (Miller et al. 2022). However, there currently are no quantitative data/models relating reductions in E2 to the degree of (increased) differentiation to male gonads and/or male-biased cohorts of fish.

Considerations for Potential Applications of the AOP (optional)

Altered sex ratios in fish can be a useful diagnostic endpoint for identifying EDCs both in field and lab settings. For example, the Fish Sexual Development Test (FSDT) has formally been adopted by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as a test guideline (No. 234) for the detecting EDCs (OECD, 2011b). The FDST is conducted in zebrafish during early development, including sexual differentiation, and uses gonadal differentiation and skewed sex ratios to detect estrogen, androgen and steroidogenesis activity of test chemicals (Dang & Kienzler 2019). This AOP directly supports the mechanistic basis for assays such as the FDST. The AOP also supports the use of in vitro assays that measure aromatase inhibition by test chemicals as a basis for predicting apical impacts on fish (e.g., Conolly et al. 2018; Doering et al. 2019a; 2019b).

References

Angelopoulou, R., Lavranos, G., & Manolakou, P. (2012). Sex determination strategies in 2012: towards a common regulatory model?. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E, 10, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-10-13

Brown, A. R., Owen, S. F., Peters, J., Zhang, Y., Soffker, M., Paull, G. C., Hosken, D. J., Wahab, M. A., & Tyler, C. R. (2015). Climate change and pollution speed declines in zebrafish populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(11), E1237–E1246. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1416269112

Conolly, R.B., G.T. Ankley, W.-Y. Cheng, M.L. Mayo, D.H. Miller, E.J. Perkins, D.L. Villeneuve and K.H. Watanabe. 2017. Quantitative adverse outcome pathways and their application to predictive toxicology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 4661-4672.

D'Cotta, H., Fostier, A., Guiguen, Y., Govoroun, M., & Baroiller, J. F. (2001). Aromatase plays a key role during normal and temperature-induced sex differentiation of tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Molecular reproduction and development, 59(3), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.1031

Dang, Z., & Kienzler, A. (2019). Changes in fish sex ratio as a basis for regulating endocrine disruptors. Environment international, 130, 104928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.104928

Doering, J.A., D.L. Villeneuve, K.A. Fay, E.C. Randolph, K.M. Jensen, M.D. Kahl, C.A. LaLone and G.T. Ankley. (2019b). Differential sensitivity to in vitro inhibition of cytochrome P450 aromatase (CYP19) activity among 18 freshwater fishes. Toxicol. Sci. 170, 394-403.

Doering, J.A., D.L. Villeneuve, S.T. Poole, B.R. Blackwell, K.M. Jensen, M.D. Kahl, A.R. Kittelson, D.J. Feifarek, C.B. Tilton, C.A. LaLone and G.T. Ankley. (2019a). Quantitative response-response relationships linking aromatase inhibition to decreased fecundity are conserved across three fishes with asynchronous oocyte development. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10470-10578.

Gao, Z.X., Wang H.P., Wallat, G., Yao, H., Rapp, D. , O ’ Bryant, P., MacDonald, R. & Wang, W. (2010). Effects of a non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor on gonadal differentiation of bluegill sunfish Lepomis macrochirus . Aquacult Res , 41 , 1282 – 9 .

Gorelick, D. A., & Halpern, M. E. (2011). Visualization of estrogen receptor transcriptional activation in zebrafish. Endocrinology, 152(7), 2690–2703. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2010-1257

Grayson, K. L., Mitchell, N. J., Monks, J. M., Keall, S. N., Wilson, J. N., & Nelson, N. J. (2014). Sex ratio bias and extinction risk in an isolated population of Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus). PloS one, 9(4), e94214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094214

Guiguen, Y., Fostier, A., Piferrer, F., & Chang, C. F. (2010). Ovarian aromatase and estrogens: a pivotal role for gonadal sex differentiation and sex change in fish. General and comparative endocrinology, 165(3), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.03.002

Holbech, H., Kinnberg, K. L., Brande-Lavridsen, N., Bjerregaard, P., Petersen, G. I., Norrgren, L., Orn, S., Braunbeck, T., Baumann, L., Bomke, C., Dorgerloh, M., Bruns, E., Ruehl-Fehlert, C., Green, J. W., Springer, T. A., & Gourmelon, A. (2012). Comparison of zebrafish (Danio rerio) and fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas) as test species in the Fish Sexual Development Test (FSDT). Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Toxicology & pharmacology : CBP, 155(2), 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2011.11.002

Kitano, T., Takamune, K., Nagahama, Y., & Abe, S. I. (2000). Aromatase inhibitor and 17alpha-methyltestosterone cause sex-reversal from genetical females to phenotypic males and suppression of P450 aromatase gene expression in Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Molecular reproduction and development, 56(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(200005)56:1<1::AID-MRD1>3.0.CO;2-3

Kwon, J. Y., Haghpanah, V., Kogson-Hurtado, L. M., McAndrew, B. J., & Penman, D. J. (2000). Masculinization of genetic female nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) by dietary administration of an aromatase inhibitor during sexual differentiation. The Journal of experimental zoology, 287(1), 46–53.

Kwon, J. Y., McAndrew, B. J., & Penman, D. J. (2001). Cloning of brain aromatase gene and expression of brain and ovarian aromatase genes during sexual differentiation in genetic male and female Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Molecular reproduction and development, 59(4), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.1042

Lau, E. S., Zhang, Z., Qin, M., & Ge, W. (2016). Knockout of Zebrafish Ovarian Aromatase Gene (cyp19a1a) by TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 Leads to All-male Offspring Due to Failed Ovarian Differentiation. Scientific reports, 6, 37357. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37357

LaLone, C.A., D.L. Villeneuve, J.A. Doering, B.R. Blackwell, T.R. Transue, C.W. Simmons, J. Swintek, S.J. Degitz, A.J. Williams and G.T. Ankley. 2018. Evidence for cross-species extrapolation of mammalian-based high-throughput screening assay results. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 13960-13971.

Luzio, A., Matos, M., Santos, D., Fontaínhas-Fernandes, A. A., Monteiro, S. M., & Coimbra, A. M. (2016). Disruption of apoptosis pathways involved in zebrafish gonad differentiation by 17α-ethinylestradiol and fadrozole exposures. Aquatic toxicology (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 177, 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.05.029

Luzio, A., Monteiro, S. M., Rocha, E., Fontaínhas-Fernandes, A. A., & Coimbra, A. M. (2016). Development and recovery of histopathological alterations in the gonads of zebrafish (Danio rerio) after single and combined exposure to endocrine disruptors (17α-ethinylestradiol and fadrozole). Aquatic toxicology (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 175, 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.03.014

Marty, M. S., Blankinship, A., Chambers, J., Constantine, L., Kloas, W., Kumar, A., Lagadic, L., Meador, J., Pickford, D., Schwarz, T., & Verslycke, T. (2017). Population-relevant endpoints in the evaluation of endocrine-active substances (EAS) for ecotoxicological hazard and risk assessment. Integrated environmental assessment and management, 13(2), 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1887

Miller, D.H., D.L. Villeneuve, K.J. Santana-Rodriguez and G.T. Ankley. 2022. A multi-dimensional matrix model for predicting the effects of male-biased sex ratios on fish populations. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 41, 1066-1077.

Muth-Köhne, E., Westphal-Settele, K., Brückner, J., Konradi, S., Schiller, V., Schäfers, C., Teigeler, M., & Fenske, M. (2016). Linking the response of endocrine regulated genes to adverse effects on sex differentiation improves comprehension of aromatase inhibition in a Fish Sexual Development Test. Aquatic toxicology (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 176, 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.04.018

Nakamura M. (2010). The mechanism of sex determination in vertebrates-are sex steroids the key-factor?. Journal of experimental zoology. Part A, Ecological genetics and physiology, 313(7), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.616

Payne, A. H., & Hales, D. B. (2004). Overview of steroidogenic enzymes in the pathway from cholesterol to active steroid hormones. Endocrine reviews, 25(6), 947–970. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2003-0030

Piferrer, F., Zanuy, S., Carrillo, M., Solar, I. I., Devlin, R. H., & Donaldson, E. M. (1994). Brief treatment with an aromatase inhibitor during sex differentiation causes chromosomally female salmon to develop as normal, functional males. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 270(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1002/JEZ.1402700304

Ramsey, M., & Crews, D. (2009). Steroid signaling and temperature-dependent sex determination-Reviewing the evidence for early action of estrogen during ovarian determination in turtles. Seminars in cell & developmental biology, 20(3), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.10.004

Rashid, H., Kitano, H., Lee, K. H., Nii, S., Shigematsu, T., Kadomura, K., Yamaguchi, A., & Matsuyama, M. (2007). Fugu (Takifugu rubripes) sexual differentiation: CYP19 regulation and aromatase inhibitor induced testicular development. Sexual development : genetics, molecular biology, evolution, endocrinology, embryology, and pathology of sex determination and differentiation, 1(5), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1159/000108935

Ruksana, S., Pandit, N. P., & Nakamura, M. (2010). Efficacy of exemestane, a new generation of aromatase inhibitor, on sex differentiation in a gonochoristic fish. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Toxicology & Pharmacology : CBP, 152(1), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.02.014

Sarre, S. D., Georges, A., & Quinn, A. (2004). The ends of a continuum: genetic and temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology, 26(6), 639–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20050

Scholz, S., & Klüver, N. (2009). Effects of endocrine disrupters on sexual, gonadal development in fish. Sexual development : genetics, molecular biology, evolution, endocrinology, embryology, and pathology of sex determination and differentiation, 3(2-3), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1159/000223078

Shen, Z. G., Fan, Q. X., Yang, W., Zhang, Y. L., Hu, P. P., & Xie, C. X. (2013). Effects of non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor letrozole on sex inversion and spermatogenesis in yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. The Biological bulletin, 225(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1086/BBLv225n1p18

Simpson, E. R., Mahendroo, M. S., Means, G. D., Kilgore, M. W., Hinshelwood, M. M., Graham-Lorence, S., Amarneh, B., Ito, Y., Fisher, C. R., & Michael, M. D. (1994). Aromatase cytochrome P450, the enzyme responsible for estrogen biosynthesis. Endocrine reviews, 15(3), 342–355. https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv-15-3-342

Strüssmann, C.A. & Nakamura, M. (2002). Morphology, endocrinology, and environmental modulation of gonadal sex differentiation in teleost fishes. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry, 26, 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023343023556

Thorpe, K. L., Marca Pereira, M. L., Schiffer, H., Burkhardt-Holm, P., Weber, K., & Wheeler, J. R. (2011). Mode of sexual differentiation and its influence on the relative sensitivity of the fathead minnow and zebrafish in the fish sexual development test. Aquatic Toxicology, 105(3–4), 412–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.07.012

Thresher, R., Gurney, R., & Canning, M. (2011). Effects of lifetime chemical inhibition of aromatase on the sexual differentiation, sperm characteristics and fertility of medaka (Oryzias latipes) and zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquatic toxicology (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 105(3-4), 355–360.

Uchida, D., Yamashita, M., Kitano, T., & Iguchi, T. (2004). An aromatase inhibitor or high water temperature induce oocyte apoptosis and depletion of P450 aromatase activity in the gonads of genetic female zebrafish during sex-reversal. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology, 137(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1095-6433(03)00178-8

Uller, T., & Helanterä, H. (2011). From the origin of sex-determining factors to the evolution of sex-determining systems. The Quarterly review of biology, 86(3), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1086/661118

Wilson, J. Y., McArthur, A. G., & Stegeman, J. J. (2005). Characterization of a cetacean aromatase (CYP19) and the phylogeny and functional conservation of vertebrate aromatase. General and comparative endocrinology, 140(1), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.10.004

Yin, Y., Tang, H., Liu, Y., Chen, Y., Li, G., Liu, X., & Lin, H. (2017). Targeted Disruption of Aromatase Reveals Dual Functions of cyp19a1a During Sex Differentiation in Zebrafish. Endocrinology, 158(9), 3030–3041. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2016-1865

Zhang, X., Li, M., Ma, H., Liu, X., Shi, H., Li, M., & Wang, D. (2017). Mutation of foxl2 or cyp19a1a Results in Female to Male Sex Reversal in XX Nile Tilapia. Endocrinology, 158(8), 2634–2647. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2017-00127