This AOP is licensed under the BY-SA license. This license allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms.

AOP: 288

Title

Inhibition of 17α-hydrolase/C 10,20-lyase (Cyp17A1) activity leads to birth reproductive defects (cryptorchidism) in male (mammals)

Short name

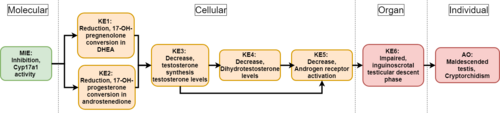

Graphical Representation

Point of Contact

Contributors

- Bérénice COLLET

- Bart van der Burg

Coaches

OECD Information Table

| OECD Project # | OECD Status | Reviewer's Reports | Journal-format Article | OECD iLibrary Published Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

This AOP was last modified on May 24, 2024 13:34

Revision dates for related pages

| Page | Revision Date/Time |

|---|---|

| Inhibition, Cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP17A1) activity | April 08, 2025 11:03 |

| Reduction, dehydroepiandrosterone | April 08, 2025 11:02 |

| Reduction, androstenedione | April 09, 2025 07:46 |

| Decrease, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels | August 13, 2025 09:04 |

| Decrease, androgen receptor activation | February 04, 2026 16:01 |

| Impaired inguinoscrotal testicular descent phase | December 03, 2024 10:36 |

| Malformation, cryptorchidism - maldescended testis | July 18, 2024 10:30 |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | January 27, 2025 03:37 |

| Inhibition of Cyp17A1 activity leads to Reduction, DHEA | April 08, 2025 11:05 |

| Inhibition of Cyp17A1 activity leads to Reduction, androstenedione | April 08, 2025 11:07 |

| Reduction, DHEA leads to Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | April 08, 2025 11:54 |

| Reduction, androstenedione leads to Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | April 08, 2025 14:49 |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to Decrease, DHT level | October 19, 2023 08:31 |

| Decrease, DHT level leads to Decrease, AR activation | April 05, 2024 08:48 |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to Decrease, AR activation | February 04, 2026 16:03 |

| Decrease, AR activation leads to Impaired inguinoscrotal phase | June 03, 2019 08:41 |

| Impaired inguinoscrotal phase leads to Malformation, cryptorchidism | December 03, 2024 10:37 |

Abstract

This Adverse Outcome Pathway describes the linkage between a decrease in 7α-hydroxylase/C17,20-lyase (Cyp17a1) activity and a specific reproductive malformation in male newborns : impaired testicular descent also called cryptorchidism.

Cyp17a1 enzyme is known to mediate 17 alpha-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase activities, the distinction between the two being functional and not genetic or structural. Mainly expressed in Leydig cells, this steroidogenic enzyme catalyzes the conversion of 17-OH-pregnenolone and 17-OH-progesterone to dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenediol, respectively. In that way, a decrease in Cyp17a1 activity would inevitably lead to a decline in both steroid precursors’ levels. As a result, this succession of key events will affect testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) synthesis and circulating levels. A direct consequence to such a drop in major androgens levels would be a decline in androgen receptor activation, causing potential disturbances in development and maintenance of the male reproductive system such as cryptorchidism. To understand this AOP, it is important to notice that the second stage of the testicular descent process called “inguinoscrotal“ is an androgen-dependent event that can be dramatically affected by variations in androgenic activity.

The present AOP is linked to EU-ToxRisk Case Study 7: Read across evaluation of reproductive toxicity of conazoles. Conazoles are fungicide used in agriculture and as pharmaceuticals for treatment of human fungal diseases. They are known to act through inhibition of CYP51 which can be related to cross-reactivity with human enzymes involved in steroid metabolism, such as CYP17a1. In that respect, the proposed AOP and associated methods can be used as a basis to assess the effects of conazoles on steroidogenesis and reproductive development.

AOP Development Strategy

Context

Strategy

Summary of the AOP

Events:

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE)

Key Events (KE)

Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|

| MIE | 1609 | Inhibition, Cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP17A1) activity | Inhibition of Cyp17A1 activity |

| KE | 1610 | Reduction, dehydroepiandrosterone | Reduction, DHEA |

| KE | 1611 | Reduction, androstenedione | Reduction, androstenedione |

| KE | 1690 | Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | Decrease, circulating testosterone levels |

| KE | 1613 | Decrease, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels | Decrease, DHT level |

| KE | 1614 | Decrease, androgen receptor activation | Decrease, AR activation |

| KE | 1615 | Impaired inguinoscrotal testicular descent phase | Impaired inguinoscrotal phase |

| AO | 1616 | Malformation, cryptorchidism - maldescended testis | Malformation, cryptorchidism |

Relationships Between Two Key Events (Including MIEs and AOs)

| Title | Adjacency | Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|

| Inhibition of Cyp17A1 activity leads to Reduction, DHEA | adjacent | High | |

| Inhibition of Cyp17A1 activity leads to Reduction, androstenedione | adjacent | High | |

| Reduction, DHEA leads to Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | adjacent | High | High |

| Reduction, androstenedione leads to Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | adjacent | High | High |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to Decrease, DHT level | adjacent | High | High |

| Decrease, DHT level leads to Decrease, AR activation | adjacent | High | High |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to Decrease, AR activation | adjacent | High | High |

| Decrease, AR activation leads to Impaired inguinoscrotal phase | adjacent | Moderate | Moderate |

| Impaired inguinoscrotal phase leads to Malformation, cryptorchidism | adjacent | High | High |

Network View

Prototypical Stressors

Life Stage Applicability

| Life stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Development | High |

Taxonomic Applicability

Sex Applicability

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

Overall Assessment of the AOP

Domain of Applicability

Life Stage Applicability

This AOP is relevant for developing male.

Sex Applicability

This AOP applies to males only.

Essentiality of the Key Events

| Key Events | ||||||||||||

| MIE | Inhibition, Cyp17a1 | CYP17a1 has a decisive function in steroidogenesis by constituting the initial step in a series of biochemical reactions. | ||||||||||

| KE1 | Reduction, DHEA conversion | 17-OH-pregnenolone is the direct precursor of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). (Miller et al., 1988 - 2011) | ||||||||||

| DHEA is the precursor of steroid hormones like testosterone and estradiol. | ||||||||||||

| KE2 | Reduction, Androstenedione conversion | 17-OH-progesterone is the direct precursor of androstenedione. (Miller et al., 1988; Liu et al., 2005) | ||||||||||

| Androstenedione is the precursor of steroid hormones like testosterone and estradiol. | ||||||||||||

| KE3 | Decrease, testosterone levels | Reduction in testosterone synthesis leads to a reduction in testosterone circulating levels. (Miller et al., 1988; Elder et al., 1985; Shiraishi et al., 2008) | ||||||||||

| KE4 | Decrease, DHT levels | Reduction in DHT synthesis leads to a reduction in DHT circulating levels. (Miller et al., 1988 - 2011 1985; Shiraishi et al., 2008) | ||||||||||

| KE5 | Decrease, AR activation | Androgen receptor activation is regulated by the binding of androgens. (Davey et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2005) | ||||||||||

| AR activity can be decreased by either a lack of steroidal ligands (testosterone, DHT) or the presence of an antagonist. | ||||||||||||

| KE6 | Impaired inguinoscrotal phase | Second phase of a two-step testis descent: the testis descends into the scrotum. (Hutson et al., 2015) | ||||||||||

| Any impairment in testis migration will directly result in the absence of one or both testes from the scrotum. | ||||||||||||

| AOP | Malformation, cryptorchidism | Insertion of the testis in another position than the scrotum. (Hutson et al., 2015a - 2015b; Boisen et al., 2004; Acerini et al., 2009) | ||||||||||

| How to measure | ||||||||||||

| MIE | Measurement in CYP17 MA-10 wild-type and CYP17 knock down MA-10 clone can be used to assess the effects of a dysfunction in CYP17a1 activity. (Liu et al., 2005) | |||||||||||

| KE1 | 17-OH-pregnenolone and DHEA can be fractionated using High Performance Liquid Chromatography. After separation, pregnenolone and DHEA levels can be quantify using immunoassay such as ELISA or Radio Immuno Assay (RIA). For both steroids, LC-MS/MS is also an option. | |||||||||||

| KE2 |

Competitive immunoenzymatic colorimetric methods (ELISA) for quantitative determination of 17-OH-progesterone and androstenedione concentration in serum or plasma are available. Progesterone and androstenedione synthesis can be monitored using radiolabeled steroid precursor in association with High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). During synthesis, steroids will incorporate the radioactive label which can be afterwards, used for quantification. First of all, HPLC combined with internal standards can be used for steroids collection, fractionation and identification. Once separated from the other steroids, progesterone and androstenedione can be finally quantified using liquid scintillation spectrometry. |

|||||||||||

| KE3 |

ELISA kit can be used for quantitative measurement of testosterone in various samples. Liquid Chromatography- tandem Mass Spectrometry is also an option. (Shiraishi et al., 2008) Detection of increase and decrease in the production of testosterone after chemical exposure can be measured using the validated H295R Steroidogenesis Assay associated with hormone measurement kits (ELISA) and/or instrumental techniques (LC-MS). (OECD, 2011) Testosterone (T) levels in a sample can be measured by (High Performance) Liquid Chromatography. After sample fractionation, testosterone can be identified by comparison with internal standards spectrum. Quantification of T levels can be performed using hormones measurements kits (ELISA), instrumental techniques (LC-MS) or liquid scintillation spectrometry (after radiolabeling). |

|||||||||||

| KE4 | DHT levels in a sample can be measured by (High Performance) Liquid Chromatography. After sample fractionation, DHT can be identify by comparison with internal standards spectrum. Quantification of DHT levels can be performed using hormones measurements kits (ELISA), instrumental techniques (LC-MS) or liquid scintillation spectrometry (after radiolabeling). (Shiraishi et al., 2008) | |||||||||||

| KE5 |

Significance of AR signaling in fetal development can be studied through a conditional deletion of the androgen receptor using a Cre/loxP approach. The recommended animal model for reproductive study is the mouse. (Kaftanovskaya et al., 2012) Also, epidemiological case-studies following mouse or humans expressing a complete androgen insensitivity allow to directly assess the effects of a lack of AR activation on the development. (Hutson 1985) Enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) kits for in vitro quantitative measurement of AR activity are available. Androgen receptors activity can be measured using bioassay such as the (Anti-)Androgen Receptor CALUX reporter gene assay. (van der Burg et al., 2010) |

|||||||||||

| KE6 | - | |||||||||||

| AOP | Cryptorchidism is a birth defect that can be highlighted by a clinical examination. The aim of this palpation is to locate the gonad and determine its lowest position without causing painful traction on the spermatic cord. (Hutson et al., 2015) | |||||||||||

Evidence Assessment

| Key Event Relations | General informations | |||||||||||

| KER1 | Inhibition, Cyp17a1 - Reduction, DHEA conversion | Cyp17a1 catalyzes the conversion of 17-OH-pregnenolone in DHEA through its 17α-hydroxylase activity. | ||||||||||

| KER2 | Inhibition, Cyp17a1 - Reduction, Androstenedione conversion | Cyp17a1 catalyzes the cleavage of c17,20 bond of 17-OH-progesterone to give androstenedione. | ||||||||||

| KER3 | Reduction, DHEA/Androstenedione - Decrease, testosterone | Levels of two main testosterone precursors (DHEA and androstenedione) are decreased (KE1-KE2) | ||||||||||

| Deficiency in these intermediate steroids directly lead to a reduction in testosterone synthesis. | ||||||||||||

| KER4 | Decrease, testosterone levels - Decrease, DHT levels | Testosterone being the precursor of DHT, a reduction in its synthesis/levels directly affects this metabolite. | ||||||||||

| KER5 | Decrease, testosterone levels - Decrease, AR activation | A lack in androgenic hormones (either testosterone or DHEA) results in a diminution of AR activation. | ||||||||||

| KER6 | Decrease, AR activation - Impaired inguinoscrotal phase | A dysfunction in androgens synthesis and AR activation leads to a defect in the inguinoscrotal stage. | ||||||||||

| AOP | Impaired inguinoscrotal phase - Malformation, cryptorchidism | A defect in the inguinoscrotal stage leads to an impairment in the testis descent to the scrotum. | ||||||||||

| Key Event Relations | Biological plausibility | ||||||||||||

| KER1 | Inhibition, Cyp17a1 - Reduction, DHEA conversion | High | Cyp17a1 is known to cleave the c17,20bond of 10-OH-pregnenolone through its 17α-hydroxylase activity. | ||||||||||

| KER2 | Inhibition, Cyp17a1 - Reduction, Androstenedione conversion | High | Most of androstenedione is synthesized through the 17,20-lyase activity of Cyp17a1. | ||||||||||

| KER3 | Reduction, DHEA/Androstenedione - Decrease, testosterone | High | This steroid can be synthesized from either DHEA/Androstenediol or Androstenedione both catalyzed by the 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase enzyme. | ||||||||||

| KER4 | Decrease, testosterone levels - Decrease, DHT levels | High | Testosterone is converted to DHT by 5alpha-reductase. | ||||||||||

| KER5 | Decrease, testosterone levels - Decrease, AR activation | High | AR is a ligand-dependent nuclear transcription factor. Its activation is known to be mediated by Testosterone and DHT. | ||||||||||

| KER6 | Decrease, AR activation - Impaired inguinoscrotal phase | Moderate | Although causes of cryptorchidism are not well-established, androgens are known to play an important role in the inguinoscrotal testicular descent | ||||||||||

| KER6 | Decrease, AR activation - Impaired inguinoscrotal phase | in both animals and humans. Variation affecting androgens levels and AR activation directly lead to defect in the inguinoscrotal phase of testis descent. | |||||||||||

| AOP | Impaired inguinoscrotal phase - Malformation, cryptorchidism | High | Any impairment affecting thie inguinoscrotal phase has direct repercussion on proper testis descent. | ||||||||||

| Empirical support | ||||||||||||

| KER1 | In 2005, Liu Y., Yao ZX., and Papadopoulos V. showed that MA-10 CYP17 knock down cells synthesize much less | |||||||||||

| pregnenolone and DHEA compared with MA-10 wild type cells. | ||||||||||||

| https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2004-0271 | ||||||||||||

| KER2 | Using MA-10 CYP17 knock down cells, Liu Y., Yao ZX., and Papadopoulos V. showed that cells without CYP17 enzyme | |||||||||||

| tend to synthesize less progesterone than MA-10 wild type cells. | ||||||||||||

| https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2004-0271 | ||||||||||||

| KER3 | - | |||||||||||

| KER4 | An enzyme immunoassay such as ELISA kit can be used for quantitative determination of DHT levels. | |||||||||||

| The ratio of serum testosterone to serum DHT shows the general activity of 5-alpha reductase. | ||||||||||||

| KER5 | Norris J.D., et al. highlighted that CYP17 inhibition using lyase–selective inhibitor antagonize AR activation. | |||||||||||

| https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI87328 | ||||||||||||

| KER6 | In 1985, Hutson studied both mice model and humans expressing a complete androgen insensitivity. This particular | |||||||||||

| research demonstrated that in such case, the testis remains in the inguinal canal or groin. | ||||||||||||

| http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92739-4 | ||||||||||||

| Kaftanovskaya et al. confirmed the previous statement in 2012 using a Cre-loxP approach study | ||||||||||||

| https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2011-1283 | ||||||||||||

| AOP | Kaftanovskaya et al. research are based on conditional deletion of the androgen receptor using a Cre/loxP approach in male mice. | |||||||||||

| Study from 2012 showed that a depletion of the AR in the gubernaculum leads to an impairment in inguinoscrotal phase and induces cryptorchidism. | ||||||||||||

| https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2011-1283 | ||||||||||||

Known Modulating Factors

Quantitative Understanding

Considerations for Potential Applications of the AOP (optional)

-

References

Acerini C.L., Miles H.L., Dunger D.B., Ong K.K. and Hughes I.A. (2009) The descriptive epidemiology of congenital and acquired cryptorchidism in a UK infant cohort. Archives of disease in childhood, 94(11):868-72 https://doi.org10.1136/adc.2008.150219

Anitha B. Alex, Sumanta K. Pal, and Neeraj Agarwal (2016) CYP17 inhibitors in prostate cancer: latest evidence and clinical potential. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology, 8(4):267-75 https://doi.org/10.1177/1758834016642370

Auchus R.J. (2004) Overview of dehydroepiandrosterone biosynthesis. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 22(4):281-8.https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-861545

Boisen K.A., Kaleva M., Main K.M., Virtanen H.E., Haavisto A.M., Schmidt I.M., Chellakooty M., Damgaard I.N., Mau C., Reunanen M., Skakkebaek N.E. and Toppari J. (2004) Difference in prevalence of congenital cryptorchidism in infants between two Nordic countries. Lancet, 17;363(9417):1264-9 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15998-9

Brinkmann A.O., Blok L.J., de Ruiter P.E., Doesburg P., Steketee K., Berrevoets C.A. and Trapman J. (1999) Mechanisms of androgen receptor activation and function. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. PMID: 10419007

Davey R.A and Grossmann M. (2016) Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. Clinical Biochemist Reviews, 37(1): 3-15. PCM4810760

Elder P.A. and Lewis J.G. (1985) An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for plasma testosterone. Journal of steroid biochemistry, 22(5):635-8.

Gao W., Bohl C.E. and Dalton J.T. (2005) Chemistry and Structural Biology of Androgen Receptor. Chemical Reviews 105(9): 3352-3370https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020456u

Hutson J.M. (1985) A biphasic model for the hormonal control of testicular descent. Lancet, 24;2(8452): 419-21http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92739-4

Hutson J.M., et al. (2015) Cryptorchidism and Hypospadias. Endotext https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279106/

Hutson J.M., Li R., Southwell B.R., Newgreen D., and Cousinery M. (2015) Regulation of testicular descent. Pediatric Surgery International, 31(4): 317-325 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-015-3673-4

Kaftanovskaya E.M., Huang Z., Barbara A.M., De Gendt K., Verhoeven G., Ivan P. Gorlov, and Agoulnik A.I. (2012) Cryptorchidism in Mice with an Androgen Receptor Ablation in Gubernaculum Testis. Molecular Endocrinology, 26(4): 598-607.https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2011-1283

Liu Y., Yao ZX., and Papadopoulos V. (2005) Cytochrome P450 17α Hydroxylase/17,20 Lyase (CYP17) Function in Cholesterol Biosynthesis: Identification of Squalene Monooxygenase (Epoxidase) Activity Associated with CYP17 in Leydig Cells. Molecular Endocrinology, 19(7): 1918-1931 https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2004-0271

Miller Walter L. (1988) Molecular Biology of Steroid Hormone Synthesis. Endocrine Reviews, 9(3): 295-318. https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv-9-3-295

Miller W.L. and Auchus R.J. (2011) The Molecular Biology, Biochemistry, and Physiology of Human Steroidogenesis and Its Disorders. Endocrine Reviews, 32(1): 81-151.https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2010-0013

Norris J.D., Ellison S.J., Baker J.G., Stagg D.B., Wardell S.E., Park S., Alley H.M., Baldi R.M., Yllanes A., Andreano K.J., Stice J.P., Lawrence S.A., Eisner J.R., Price D.K., Moore W.R., Figg W.D. and, McDonnell D.P. (2017) Androgen receptor antagonism drives cytochrome P450 17A1 inhibitor efficacy in prostate cancer. The journal of clinical investigation, 127(6):2326-2338 https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI87328

OECD Guideline For the Testing of Chemicals - H295R Steroidogenesis Assay (2011)https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/iccvam/suppdocs/feddocs/oecd/oecd-tg456-2011-508.pdf

Petrunak E.M., DeVore N.M., Patrick R. Porubsky PR.., and Scott E.E.(2014) Structures of human steroidogenic cytochrome P450 17A1 with substrates. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(47): 32952–32964 https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.610998

Roelofs M.J., Piersma A.H., van den Berg M. and van Duursen M.B. (2013) The relevance of chemical interactions with CYP17 enzyme activity: assessment using a novel in vitro assay. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 1;268(3):309-17 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2013.01.033

Shiraishi S., Lee P.W., Leung A., Goh V.H., Swerdloff R.S. and Wang C. (2008) Simultaneous measurement of serum testosterone and dihydrotestosterone by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clinical chemistry, 54(11): 1855-63.https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2008.103846

Storbeck K., Swart P., Africander D., Conradie R., Louw R. and.Swart A.C. (2011) 16α-Hydroxyprogesterone: Origin, biosynthesis and receptor interaction. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 336(1-2): 92-101https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2010.11.016

van der Burg B., Winter R., Man HY., Vangenechten C., Berckmans P., Weimer M., Witters M. and van der Linden S. (2010) Optimization and prevalidation of the in vitro AR CALUX method to test androgenic and antiandrogenic activity of compounds. Reproductive Toxicology, 30(1):18-24 https://doi.org/0.1016/j.reprotox.2010.04.012

Vinggaard A.M., Christiansen S., Laier P., Poulsen M.E., Breinholt V, Jarfelt K., Jacobsen H., Dalgaard M., Nellemann C. and Hass U. (2005) Perinatal exposure to the fungicide prochloraz feminizes the male rat offspring. Toxicological Sciences, 85:886–897https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfi150