This AOP is licensed under the BY-SA license. This license allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms.

AOP: 570

Title

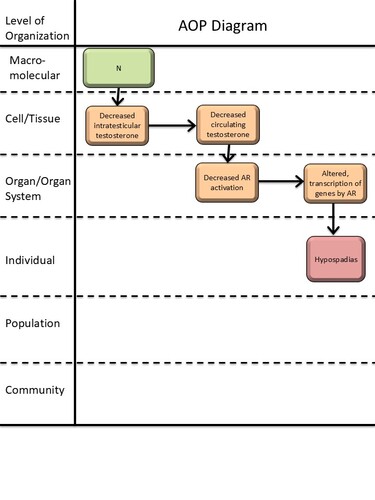

Decreased testosterone synthesis leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring

Short name

Graphical Representation

Point of Contact

Contributors

- Terje Svingen

- Emilie Elmelund

Coaches

OECD Information Table

| OECD Project # | OECD Status | Reviewer's Reports | Journal-format Article | OECD iLibrary Published Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

This AOP was last modified on September 18, 2025 07:14

Revision dates for related pages

| Page | Revision Date/Time |

|---|---|

| Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels | January 27, 2025 11:33 |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | January 27, 2025 03:37 |

| Decrease, androgen receptor activation | February 04, 2026 16:01 |

| Altered, Transcription of genes by the androgen receptor | April 05, 2024 09:28 |

| Hypospadias, increased | September 18, 2025 03:48 |

| Decrease, intratesticular testosterone leads to Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | May 07, 2025 04:19 |

| Decrease, intratesticular testosterone leads to Hypospadias | September 18, 2025 06:38 |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to Decrease, AR activation | February 04, 2026 16:03 |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to Hypospadias | September 18, 2025 06:53 |

| Decrease, AR activation leads to Altered, Transcription of genes by the AR | April 05, 2024 08:50 |

| Decrease, AR activation leads to Hypospadias | September 18, 2025 05:48 |

| Dibutyl phthalate | November 29, 2016 18:42 |

| Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate | November 29, 2016 18:42 |

Abstract

This AOP links in utero decreased intratesticular testosterone levels with hypospadias in male offspring. Hypospadias is a common reproductive disorder with a prevalence of up to ~1/125 newborn boys (Leunbach et al., 2025; Paulozzi, 1999). Developmental exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals is suspected to contribute to some cases of hypospadias (Mattiske & Pask, 2021). Hypospadias can be indicative of fetal disruptions to male reproductive development, and is associated with short anogenital distance and cryptorchidism (Skakkebaek et al., 2016). Thus, hypospadias is included as an endpoint in OECD test guidelines (TG) for developmental and reproductive toxicity (TG 414, 416, 421/422, and 443; (OECD, 2001, 2016b, 2016a, 2018a, 2018b)), as both a measurement of adverse reproductive effects and a direct clinical adverse outcome.

Testosterone is one of the two main steroid sex hormones essential for male reproductive development. Testosterone is primarily, but not exclusively, produced in the testes and then secreted into the circulation. In peripheral reproductive tissues, testosterone is either converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) or directly activates the androgen receptor (AR). DHT is more potent than testosterone in activating the AR, and activation of AR by either androgen initiates differentiation of the male phenotype, including development of the penis (Amato et al., 2022; Davey & Grossmann, 2016). This AOP delineates the evidence that decreasing testicular testosterone production lowers circulating testosterone levels and consequently AR activation, thereby disrupting penis development and causing hypospadias. In this AOP, the first KE is not considered an MIE, as testicular testosterone production can be obstructed by various routes. The AOP does not discriminate whether the reduction in AR activation is due to direct lack of testosterone at the AR or due to decreased conversion of testosterone to DHT, as there is not sufficient information on this. The AOP is supported by in vitro experiments upstream of AR activation and by in vivo and human case studies downstream of AR activation. Downstream of a reduction in AR activation, the molecular mechanisms of hypospadias development are not fully delineated, highlighting a knowledge gap in this AOP. Thus, the AOP has potential for inclusion of additional KEs and elaboration of molecular causality links, once these are established. Given that hypospadias is both a clinical and toxicological endpoint, this AOP is considered highly relevant in a regulatory context.

AOP Development Strategy

Context

This AOP is a part of an AOP network for reduced androgen receptor activation causing hypospadias in male offspring. The other AOPs in this network are AOP-477 (‘Androgen receptor antagonism leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring’), and AOP-571 (‘5α-reductase inhibition leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring’). The purpose of the AOP network is to organize the well-established evidence for anti-androgenic mechanisms-of-action leading to hypospadias, thus informing predictive toxicology and identifying knowledge gaps for investigation and method development.

This work received funding from the European Food and Safety Authority (EFSA) under Grant agreement no. GP/EFSA/PREV/2022/01 and from the Danish Environmental Protection Agency under the Danish Center for Endocrine Disrupters (CeHoS).

Strategy

The OECD AOP Developer’s Handbook was followed alongside pragmatic approaches (Svingen et al., 2021).

KEs and upstream KER-3448 (‘Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels leads to decrease, circulation testosterone levels’), KER-2131 (‘Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to decrease, AR activation’), and KER-2124 (‘Decrease, AR activation leads to altered, transcription of genes by AR’) were considered canonical knowledge and part of an upstream anti-androgenic network developed using mainly key review articles (Draskau et al., 2024; Svingen et al., 2025). The non-adjacent KER-3488, KER-3350, and KER-2828 linking decreased intratesticular testosterone, circulating testosterone, and AR activation, respectively, with hypospadias were developed using a systematic weight-of-evidence approach, following methodology outlined in (Holmer et al., 2024). Articles were retrieved by literature searches in PubMed and Web of Science and extensive screening using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Evaluation of methodological reliability of in vivo animal studies was performed using the Science in Risk Assessment and Policy (SciRAP) online tool. For KER-3488 and KER-3350 regarding testosterone levels, articles were included if there was a decrease in fetal testosterone levels and hypospadias was assessed in male offspring. For KER-2828, there are currently no in vivo methods to measure AR activation in mammals, and instead six chemicals with known anti-androgenic mechanisms-of-action were chosen for the empirical evidence for this KER. To supplement the in vivo toxicity studies, human case studies and epidemiologic studies were included in the KERs. These studies were not systematically evaluated for reliability but served as supporting evidence.

Regarding the inclusion of KEs and KERs, the rationale for the upstream anti-androgenic network is detailed in (Draskau et al., 2024). KE-2298 (‘Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels’) was added to discriminate between the large difference in testosterone levels between testes and circulation (Coviello et al., 2004; McLachlan et al., 2002; Turner et al., 1984). The link between the upstream network, more specifically KE-286 (‘altered, transcription of genes by AR’), and AO-2082 (‘hypospadias’) likely contains a tissue-specific KE that has not been developed, as sufficient evidence is not yet available. Thus, for now, the most evidence for the link of the anti-androgenic network on hypospadias is captured by KER-2828.

Summary of the AOP

Events:

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE)

Key Events (KE)

Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|

| KE | 2298 | Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels | Decrease, intratesticular testosterone |

| KE | 1690 | Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | Decrease, circulating testosterone levels |

| KE | 1614 | Decrease, androgen receptor activation | Decrease, AR activation |

| KE | 286 | Altered, Transcription of genes by the androgen receptor | Altered, Transcription of genes by the AR |

| AO | 2082 | Hypospadias, increased | Hypospadias |

Relationships Between Two Key Events (Including MIEs and AOs)

| Title | Adjacency | Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|

| Decrease, intratesticular testosterone leads to Hypospadias | non-adjacent | Moderate | |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to Hypospadias | non-adjacent | Low | |

| Decrease, AR activation leads to Hypospadias | non-adjacent | High |

Network View

Prototypical Stressors

Life Stage Applicability

| Life stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Foetal | High |

Taxonomic Applicability

Sex Applicability

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

Overall Assessment of the AOP

Domain of Applicability

Although the upstream part of the AOPN has a broad applicability domain, the overall AOPN is considered only applicable to male mammals during fetal life, restricted by the applicability of KE-2298 (‘Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels’) and KER-3488 (‘Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels leads to hypospadias’), KER-3350 (‘Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to hypospadias’), and KER-2828 (‘Decrease AR activation leads to hypospadias’). By definition, testes are the primary sex organs in males, and the term hypospadias is mainly used for describing malformation of the male and not female external genitalia. The genital tubercle is programmed by androgens to differentiate into a penis in fetal life in the masculinization programming window, followed by the morphological differentiation (Welsh et al., 2008). In humans, hypospadias is diagnosed at birth and can also often be observed in rodents at this time point, although the rodent penis does not finish developing until a few weeks after birth (Baskin & Ebbers, 2006; Sinclair et al., 2017). The disruption to androgen programming leading to hypospadias thus happens in the fetal life stage, but the AO is best detected postnatally. Regarding taxonomic applicability, hypospadias has mainly been identified in rodents (rats and mice) and humans, and the evidence in this AOP is almost exclusively from these species. It is, however, biologically plausible that the AOP is applicable to other mammals as well, given the conserved role of androgens in mammalian reproductive development, and hypospadias has been observed in many domestic animal and wildlife species, albeit not coupled to reduced testosterone levels.

Essentiality of the Key Events

|

Event |

Evidence |

Uncertainties and inconsistencies |

|

KE-2298 Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels (moderate) |

Biological plausibility provides strong support for the essentiality of this event as the testes are the main sites of testosterone production in male mammals, and testosterone is a ligand for the AR and one of the primary drivers of penis development.

Experimental evidence with phthalates lowering intratesticular testosterone supports the essentiality (see KE 3488)

Human case studies indirectly support the essentiality as mutations in steroidogenesis enzymes and gonadal dysgenesis are associated with low circulating testosterone levels and hypospadias (as listed in table 4, KER 2828) |

In the human studies, testosterone levels were only measured postnatally and not in fetal life. |

|

KE-1690 Decrease, circulating testosterone levels (moderate) |

Biological plausibility provides strong support for the essentiality of this event as testosterone is a ligand for the AR and one of the primary drivers of penis development

Human case studies support the essentiality as low circulating testosterone levels have been associated with hypospadias (as listed in table 4 in KER-2828). |

In human case studies, testosterone levels were only measured postnatally and not in fetal life. As hypospadias is a congenital malformation, it cannot be “reversed” by testosterone treatment. |

|

KE-1614 Decrease, AR activation (moderate) |

Biological plausibility provides strong support for the essentiality of this event, as AR activation is critical for normal penis development.

Conditional or full knockout of Ar in mice results in partly or full sex-reversal of males, including a female-like urethral opening (Willingham et al., 2006; Yucel et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2015). Human subjects with AR mutations may also have associated hypospadias (as presented in table 4 in KER 2828). |

|

|

KE-286 Altered, transcription of genes by AR (low) |

Biological plausibility provides support for the essentiality of this event. AR is a nuclear receptor and transcription factor regulating transcription of genes, and androgens, acting through AR, are essential for normal male penis development. Known AR-responsive genes active in normal penis development have been thoroughly reviewed (Amato et al., 2022). |

There are currently no AR-responsive genes proved to be causally involved in hypospadias, and it is known that the AR can also signal through non-genomic actions (Leung & Sadar, 2017). |

|

Event |

Direct evidence |

Indirect evidence |

Contradictory evidence |

Overall essentiality assessment |

|

KE-2298 |

|

** |

* |

Moderate |

|

KE-1690 |

|

*** |

* |

Moderate |

|

KE-1614 |

** |

|

|

Moderate |

|

KE-286 |

|

* |

|

Low |

Evidence Assessment

The confidence in each of the KERs comprising the AOP are judged as high, with both high biological plausibility and high confidence in the empirical evidence. The mechanistic link between KE-286 (‘altered, transcription of genes by AR’) and AO-2082 (‘hypospadias’) is not established, but given the high confidence in the KERs including the non-adjacent KER-2828 linking to the AO, the overall confidence in the AOP is judged as high.

|

KER |

Biological Plausibility |

Empirical Evidence |

Rationale |

|

KER-3448 Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels leads to decrease, circulating testosterone levels |

High |

High (canonical) |

It is well established that testes are the primary testosterone-producing organs in male mammals. In vivo studies have shown that exposure to substances that lowers intratesticular testosterone also lowers circulating testosterone levels (Svingen et al., 2025). |

|

KER-2131 Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to decrease, AR activation |

High |

High (canonical) |

It is well established that testosterone activates the AR. Direct evidence for this KER is not possible since KE 1614 can currently not be measured and is considered an in vivo effect. Indirect evidence using proxy read-outs of AR activation, either in vitro or in vivo strongly supports the relationship (Draskau et al., 2024). |

|

KER-2124 Decrease, AR activation leads to altered, transcription of genes by AR |

High |

High (canonical) |

It is well established that the AR regulates gene transcription. In vivo animal studies and human genomic profiling show tissue-specific changes to gene expression upon disruption of AR (Draskau et al., 2024). |

|

KER-3488 Decrease, intratesticular testosterone leads to hypospadias |

High |

Moderate |

It is well established that testicular testosterone is one of the primary drivers of penis development. In vivo animal studies support that reductions in fetal testicular testosterone can cause hypospadias in male offspring. One study supports dose concordance, where diisocytol caused reduced ex vivo testosterone production in rats at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg bw/day, while hypospadias was observed in male offspring at 1 mg/kg bw/day (Saillenfait et al., 2013). |

|

KER-3350 Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to hypospadias |

High |

Low |

It is well established that testosterone is one of the primary drivers of penis development. In vivo evidence for this KER is sparse, but human case studies of subjects with low testosterone levels (postnatally) and associated hypospadias support the KER.

|

|

KER-2828 Decrease, AR activation leads to hypospadias |

High |

High |

It is well established that AR drives penis differentiation. Numerous in vivo toxicity studies and human case studies indirectly show that decreased AR activation leads to hypospadias, with few inconsistencies. The empirical evidence moderately supports dose, temporal, and incidence concordance for the KER. |

Known Modulating Factors

|

Modulating factor (MF) |

Influence or Outcome |

KER(s) involved |

|

Genotype |

Extended CAG repeat length in AR is associated with reduced AR activity (Chamberlain et al., 1994; Tut et al., 1997). This MF could initiate the AOP at lower stressor doses. |

KER-2131, KER-2124, KER-2828 |

|

Androgen deficiency syndrome |

Low circulating testosterone levels due to hypogonadism (Bhasin et al., 2010). This MF lowers general testicular testosterone production and thus initiates the AOP at lower stressor doses. |

KER-2131 |

Quantitative Understanding

The quantitative understanding of this AOP is judged as low.

A model for phthalate-induced malformations has been developed which aims to predict the frequency of hypospadias related to a phthalate’s reduction in ex vivo testosterone production. The model predicted that a 60% reduction in testosterone levels would induce hypospadias, although the predictivity of this model was not good when tested for one phthalate (Earl Gray et al., 2024).

Considerations for Potential Applications of the AOP (optional)

References

Amato, C. M., Yao, H. H.-C., & Zhao, F. (2022). One Tool for Many Jobs: Divergent and Conserved Actions of Androgen Signaling in Male Internal Reproductive Tract and External Genitalia. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13, 910964. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.910964

Baskin, L., & Ebbers, M. (2006). Hypospadias: Anatomy, etiology, and technique. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 41(3), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.059

Bhasin, S., Cunningham, G. R., Hayes, F. J., Matsumoto, A. M., Snyder, P. J., Swerdloff, R. S., & Montori, V. M. (2010). Testosterone Therapy in Men with Androgen Deficiency Syndromes: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 95(6), 2536–2559. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-2354

Chamberlain, N. L., Driver, E. D., & Miesfeld, R. L. (1994). The length and location of CAG trinucleotide repeats in the androgen receptor N-terminal domain affect transactivation function. Nucleic Acids Research, 22(15), 3181–3186. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.15.3181

Coviello, A. D., Bremner, W. J., Matsumoto, A. M., Herbst, K. L., Amory, J. K., Anawalt, B. D., Yan, X., Brown, T. R., Wright, W. W., Zirkin, B. R., & Jarow, J. P. (2004). Intratesticular Testosterone Concentrations Comparable With Serum Levels Are Not Sufficient to Maintain Normal Sperm Production in Men Receiving a Hormonal Contraceptive Regimen. Journal of Andrology, 25(6), 931–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb03164.x

Davey, R. A., & Grossmann, M. (2016). Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. The Clinical Biochemist. Reviews, 37(1), 3–15.

Draskau, M., Rosenmai, A., Bouftas, N., Johansson, H., Panagiotou, E., Holmer, M., Elmelund, E., Zilliacus, J., Beronius, A., Damdimopoulou, P., van Duursen, M., & Svingen, T. (2024). Aop Report: An Upstream Network for Reduced Androgen Signalling Leading to Altered Gene Expression of Ar Responsive Genes in Target Tissues. Environ Toxicol Chem, In Press.

Earl Gray, L. J., Lambright, C. S., Evans, N., Ford, J., & Conley, J. M. (2024). Using targeted fetal rat testis genomic and endocrine alterations to predict the effects of a phthalate mixture on the male reproductive tract. Current Research in Toxicology, 7, 100180–100180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2024.100180

Holmer, M. L., Zilliacus, J., Draskau, M. K., Hlisníková, H., Beronius, A., & Svingen, T. (2024). Methodology for developing data-rich Key Event Relationships for Adverse Outcome Pathways exemplified by linking decreased androgen receptor activity with decreased anogenital distance. Reproductive Toxicology, 128, 108662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2024.108662

Leunbach, T. L., Berglund, A., Ernst, A., Hvistendahl, G. M., Rawashdeh, Y. F., & Gravholt, C. H. (2025). Prevalence, Incidence, and Age at Diagnosis of Boys With Hypospadias: A Nationwide Population-Based Epidemiological Study. Journal of Urology, 213(3), 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000004319

Leung, J. K., & Sadar, M. D. (2017). Non-Genomic Actions of the Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00002

Mattiske, D. M., & Pask, A. J. (2021). Endocrine disrupting chemicals in the pathogenesis of hypospadias; developmental and toxicological perspectives. Current Research in Toxicology, 2, 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2021.03.004

McLachlan, R. I., O’Donnell, L., Stanton, P. G., Balourdos, G., Frydenberg, M., de Kretser, D. M., & Robertson, D. M. (2002). Effects of Testosterone Plus Medroxyprogesterone Acetate on Semen Quality, Reproductive Hormones, and Germ Cell Populations in Normal Young Men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 87(2), 546–556. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.87.2.8231

OECD. (2001). Test No. 416: Two-Generation Reproduction Toxicity [OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4]. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264070868-en

OECD. (2016a). Test No. 421: Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264264380-en

OECD. (2016b). Test No. 422: Combined Repeated Dose Toxicity Study with the Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264264403-en

OECD. (2018a). Test No. 414: Prenatal Developmental Toxicity Study. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264070820-en

OECD. (2018b). Test No. 443: Extended One-Generation Reproductive Toxicity Study. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264185371-en

Paulozzi, L. J. (1999). International trends in rates of hypospadias and cryptorchidism.

Saillenfait, A., Sabaté, J., Robert, A., Cossec, B., Roudot, A., Denis, F., & Burgart, M. (2013). Adverse effects of diisooctyl phthalate on the male rat reproductive development following prenatal exposure. Reproductive Toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.), 42, 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.09.004

Sinclair, A., Cao, M., Pask, A., Baskin, L., & Cunha, G. (2017). Flutamide-induced hypospadias in rats: A critical assessment. Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity, 94, 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2016.12.001

Skakkebaek, N. E., Rajpert-De Meyts, E., Louis, G. M. B., Toppari, J., Andersson, A.-M., Eisenberg, M. L., Jensen, T. K., Jorgensen, N., Swan, S. H., Sapra, K. J., Ziebe, S., Priskorn, L., & Juul, A. (2016). Male Reproductive Disorders And Fertility Trends: Influences Of Environement And Genetic susceptibility. PHYSIOLOGICAL REVIEWS, 96(1), 55–97. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00017.2015

Svingen, T., Elmelund, E., Holmer, M. L., Bindel, A. O., Holbech, H., & Draskau, M. K. (2025). AOP report: Adverse Outcome Pathway Network for Developmental Androgen Signalling-Inhibition Leading to Short Anogenital Distance in Male Offspring. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, vgaf221. https://doi.org/10.1093/etojnl/vgaf221

Svingen, T., Villeneuve, D. L., Knapen, D., Panagiotou, E. M., Draskau, M. K., Damdimopoulou, P., & O’Brien, J. M. (2021). A Pragmatic Approach to Adverse Outcome Pathway Development and Evaluation. Toxicological Sciences, 184(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfab113

Turner, T. T., Jones, C. E., Howards, S. S., Ewing, L. L., Zegeye, B., & Gunsalus, G. L. (1984). On the androgen microenvironment of maturing spermatozoa. Endocrinology, 115(5), 1925–1932. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-115-5-1925

Tut, T. G., Ghadessy, F. J., Trifiro, M. A., Pinsky, L., & Yong, E. L. (1997). Long Polyglutamine Tracts in the Androgen Receptor Are Associated with Reduced Trans -Activation, Impaired Sperm Production, and Male Infertility 1. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 82(11), 3777–3782. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.82.11.4385

Welsh, M., Saunders, P. T. K., Fisken, M., Scott, H. M., Hutchison, G. R., Smith, L. B., & Sharpe, R. M. (2008). Identification in rats of a programming window for reproductive tract masculinization, disruption of which leads to hypospadias and cryptorchidism. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 118(4), 1479–1490. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI34241

Willingham, E., Agras, K., Souza, A. J. de, Konijeti, R., Yucel, S., Rickie, W., Cunha, G., & Baskin, L. (2006). Steroid receptors and mammalian penile development: An unexpected role for progesterone receptor? The Journal of Urology, 176(2), 728–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.078

Yucel, S., Liu, W., Cordero, D., Donjacour, A., Cunha, G., & Baskin, L. (2004). Anatomical studies of the fibroblast growth factor-10 mutant, Sonic Hedge Hog mutant and androgen receptor mutant mouse genital tubercle. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 545, 123–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8995-6_8

Zheng, Z., Armfield, B., & Cohn, M. (2015). Timing of androgen receptor disruption and estrogen exposure underlies a spectrum of congenital penile anomalies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(52), E7194-203. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1515981112