AOP ID and Title:

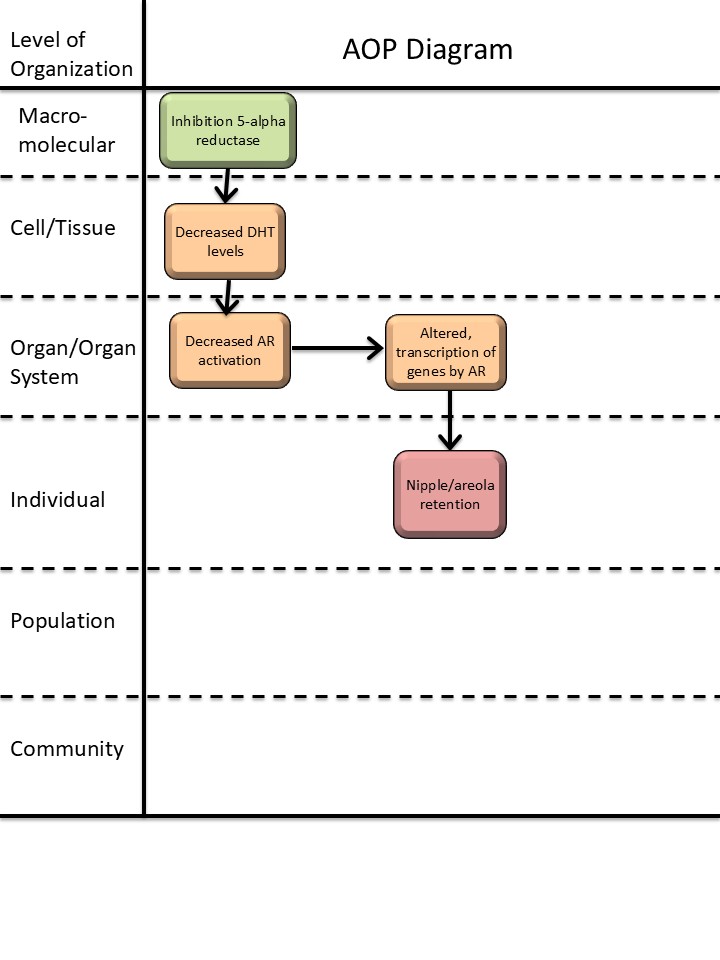

Graphical Representation

Status

| Author status | OECD status | OECD project | SAAOP status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under development: Not open for comment. Do not cite |

Abstract

This AOP links inhibition of 5α-reductase during fetal life with increased nipple/areola retention (NR) in male rodent offspring. NR, measured around 2 weeks postpartum, is a marker for disrupted masculinization of male rodents (primarily investigated in laboratory rats and mice) and is associated with general feminization of male offspring.

5α-reductase is an enzyme that converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). In normal male reproductive development, DHT activates the androgen receptor (AR) in many peripheral reproductive tissues to drive differentiation of the male phenotype, including regression of nipple anlagen in male rats and mice. While testosterone also acts directly at the AR, DHT is 5-10 times more potent and in tissues peripheral to the testes, conversion to DHT is necessary for proper masculinization (Amato et al., 2022; Davey & Grossmann, 2016).

This AOP delineates the evidence that inhibition of 5α-reductase reduces DHT levels and consequently AR activation, causing retention of nipples in male rodents. The AOP is supported by in vitro experiments upstream of AR activation and by in vivo studies downstream of AR activation. Downstream of a reduction in AR activation, the molecular mechanisms of NR are unclear, highlighting a knowledge gap in this AOP and potential for further development.

The confidence in each of the KERs comprising the AOP is judged as high, with both high biological plausibility and high confidence in empirical evidence. The mechanistic link between KE-286 (‘altered, transcription of genes by AR’) and AO 1786 (‘increase, nipple retention’) is not established, but given the high confidence in the KERs, the overall confidence in the AOP is judged as high.

The AOP supports the regulatory application of NR as a measure of endocrine disruption relevant for human health and the use of NR as an indicator of anti-androgenicity in environmentally relevant species. Even though NR cannot be directly translated to a human endpoint, the AOP is considered human relevant since NR is a clear readout of reduced androgen action and masculinization during development and is considered an ‘adverse outcome’ in OECD test guidelines (TG 443, TG 421, TG 422). The AOP also holds utility for informing on anti-androgenicity more generally, as this modality is highly relevant across mammalian species and vertebrates more broadly due to the conserved nature of the AR and its implication in sexual differentiation across species.

Background

This AOP is a part of an AOP network for reduced AR activation leading to increased NR in male offspring. The other AOPs in this network are AOP 344 (‘Androgen receptor antagonism leading to increased nipple retention in male (rodent) offspring’), and AOP 575 (‘Decreased testosterone synthesis leading to increased nipple retention in male (rodent) offspring’). The purpose of the AOP network is to organize the well-established evidence for anti-androgenic mechanisms-of-action leading to increased NR. It can be used in identification and assessment of endocrine disruptors and to inform predictive toxicology, identification of knowledge gaps for investigation and method development.

This work received funding from the European Food and Safety Authority (EFSA) under Grant agreement no. GP/EFSA/PREV/2022/01.

Summary of the AOP

Events

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE), Key Events (KE), Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Sequence | Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIE | 1617 | Inhibition, 5α-reductase | Inhibition, 5α-reductase | |

| KE | 1613 | Decrease, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels | Decrease, DHT level | |

| KE | 1614 | Decrease, androgen receptor activation | Decrease, AR activation | |

| KE | 286 | Altered, Transcription of genes by the androgen receptor | Altered, Transcription of genes by the AR | |

| AO | 1786 | Nipple retention (NR), increased | nipple retention, increased |

Key Event Relationships

| Upstream Event | Relationship Type | Downstream Event | Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition, 5α-reductase | adjacent | Decrease, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels | High | |

| Decrease, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels | adjacent | Decrease, androgen receptor activation | High | |

| Decrease, androgen receptor activation | adjacent | Altered, Transcription of genes by the androgen receptor | High | |

| Decrease, androgen receptor activation | non-adjacent | Nipple retention (NR), increased | High |

Stressors

| Name | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Finasteride |

Overall Assessment of the AOP

Domain of Applicability

Life Stage Applicability| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Foetal | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

The upstream part of the AOP has a broad applicability domain, but KER 3348 (Decrease, AR activation, leads to increased nipple retention) is considered only directly applicable to male rodent (current evidence primarily from rats and mice) during fetal life, restricting the applicability of the AOP. NR is specific to animals with sexual dimorphism in the number of nipples, a feature most prominently investigated in laboratory rats and mice. It is, however, biologically plausible that the AOP is applicable to other rodent species. The process of retention of nipples by disruption of androgen programming happens in the fetal life stage, but the AO is detected postnatally. In the males of mice and rats, the nipple anlagen are programmed during fetal development by androgens to regress, leading to no visible nipples in males postnatally, while females exhibit nipples. This AOP only contains empirical evidence for the applicability to male rats, but the AOP is considered equally applicable to male mice, as these also normally exhibit nipple regression stimulated by androgens. Moreover, the AOP is relevant for other taxa, including humans, as NR in male rodents indicates a reduction in fetal masculinization. NR is therefore included as a mandatory endpoint in multiple OECD Test Guideline studies for developmental and reproductive toxicity and is considered applicable as an adverse outcome to set NOAELs and LOAELs of substances in human health risk assessments.

Essentiality of the Key Events

|

Event |

Evidence |

Uncertainties, inconsistencies and contradictory evidence |

|

MIE-1617 Inhibition, 5α-reductase

HIGH: This MIE is usually measured in vitro, whereas the downstream events in the AOP are usually measured in vivo. Canonical knowledge of normal male reproductive development provides strong support for essentiality, along with 5α-reductase knockout models and models using exposure to 5α-reductase inhibitors. |

Biological plausibility provides strong support for the essentiality of this event, as DHT, produced by 5α-reductase, is a ligand of the AR and a primary driver of normal regression of nipple anlagen in male fetuses (Imperato-McGinley et al., 1986).

Indirect evidence of impact of inhibition of 5α-reductase (MIE-1617) in vitro on AR activity in vitro: • Finasteride, a specific inhibitor of 5α-reductase, can decrease proliferation of prostate cancer cells in vitro, a proxy read-out of AR activity (Bologna et al., 1995).

Direct evidence of impact of inhibition of 5α-reductase (MIE-1617) in vivo on decreased DHT levels (KE-1613): • Lack of 5α-reductase type 2 activity by e.g. inhibitor or KO decrease DHT levels locally in tissues and blood. This is demonstrated in humans, rats, monkeys, and mice (Robitaille & Langlois, 2020).

Indirect evidence of impact of inhibition of 5α-reductase (MIE-1617) in vivo on decreased DHT levels (KE-1613): • Men with androgenic alopecia treated with finasteride or dutasteride presented with decreased DHT levels in serum (Clark et al., 2004; Drake et al., 1999).

Direct evidence of impact of inhibition of 5α-reductase (MIE-1617) in vivo on increased nipple retention (AO-1786): • Exposure to the 5α-reductase inhibitors leads to increased retention of nipples in male offspring after in utero exposure (Christiansen et al., 2009; Imperato-McGinley et al., 1986). |

|

|

KE-1613 Decreased, DHT levels

HIGH: Canonical knowledge of normal male reproductive development provides strong support for essentiality, along with rescue studies specifically demonstrating how DHT is essential for normal regression of nipple anlagen in male offspring.

|

Biological plausibility provides strong support for the essentiality of this event. Androgens are AR ligands and main drivers for the regression of nipple anlagen in male offspring (Goldman et al., 1976), with DHT playing an important role (Imperato-McGinley et al., 1986).

Indirect evidence of impact of decreased DHT levels (KE-1613) on AR activity in vivo (KE-1614): • Androgen deprivation is used as treatment for prostate cancer, including 5α-reductase inhibitors, to reduce DHT levels and cancer growth (Aggarwal et al., 2010).

Indirect evidence of impact of decreased DHT levels (KE-1613) on AR activity in vitro: • Increasing concentrations of DHT lead to increasing AR activation in vitro in AR reporter gene assays (OECD, 2023; Williams et al., 2017).

Indirect evidence of impact of decreased DHT levels (KE-1613) on AR activity in vivo: • 5α-reductase 2 deficiency is an autosomal recessive condition in which 46,XY subjects with bilateral testes and normal testosterone production have impaired virilization during fetal life due to diminished DHT (Mendonca et al., 2016).

Direct evidence of impact of decreased DHT levels (KE-1613) on increased nipple retention (AO-1786). • Nipple formation is inhibited in female rat fetuses exposed to DHT during gestation (Goldman et al., 1976). • Exposure to the 5α-reductase inhibitor 390 MSD leads to increased retention of nipples in male rats after in utero exposure, whereas simultaneous exposure to DHT reverses the effects (Imperato-McGinley et al., 1986). |

|

|

KE-1614 Decreased, AR activation

HIGH: There is experimental evidence from mutant mice insensitive to androgens showing that the AR is essential for nipple retention in male offspring. There is also evidence from exposure studies in animals that substances antagonizing AR induce nipple retention in male pups. |

Biological plausibility provides strong support for the essentiality of this event, as AR activation is critical for normal regression of nipple anlagen in male embryos.

Indirect evidence of the impact of decreased AR activation (KE-1614) on altered gene transcription by AR (KE-286): • Exposure to known anti-androgenic chemicals induces a changed gene expression pattern, e.g. in neonatal pig ovaries (Knapczyk-Stwora et al., 2019).

Direct evidence of the impact of decreased AR activation (KE-1614) on altered gene transcription by AR (KE-286): • Male AR KO mice have altered gene expression pattern in a broad range of organs (see KER-2124).

Indirect evidence of impact of decreased AR activation (KE-1614) on increased nipple retention (AO-1786): • Rat in vivo exposure to vinclozolin, procymidone and flutamide, which are known AR antagonists, leads to increased nipple retention in offspring (see KER-3348).

Direct evidence of impact of decreased AR activation (KE-1614) on increased nipple retention (AO-1786): • Male Tfm mutant mice, which are insensitive to androgens and believed to be so due to a nonfunctional androgen receptor, present with retained nipples (Kratochwil & Schwartz, 1976) |

|

|

KE-286 Altered, trans. of genes by AR

LOW: Strongest support for essentiality comes from biological plausibility. However, exact transcriptional effects and causality remain to be fully characterized. |

Biological plausibility provides support for the essentiality of this event. AR is a nuclear receptor and transcription factor regulating transcription of genes, and androgens, acting through AR, are essential for normal regression of nipple anlagen in male fetuses. |

There are currently no AR-responsive genes proved to be causally involved in nipple retention, and it is known that AR can also signal through non-genomic actions (Leung & Sadar, 2017). |

|

Event |

Direct evidence |

Indirect evidence |

Contradictory evidence |

Overall essentiality assessment |

|

MIE-1617 |

*** |

** |

|

High |

|

KE-1613 |

*** |

** |

|

High |

|

KE-1614 |

*** |

*** |

|

High |

|

KE-286 |

|

|

|

Low (biological plausibility) |

*Low level of evidence (some support for essentiality), ** Intermediate level of evidence (evidence for impact on one or more downstream KEs), ***High level of evidence (evidence for impact on AO).

Weight of Evidence Summary

The confidence in each of the KERs comprising the AOP is judged as high, with both high biological plausibility and high confidence in empirical evidence. The mechanistic link between KE-286 (‘altered, transcription of genes by AR’) and AO 1786 (‘increase, nipple retention’) is not established, but given the high confidence in the KERs, the overall confidence in the AOP is judged as high.

|

KER |

Biological Plausibility |

Empirical Evidence |

Rationale |

|

KER-1880 Inhibition, 5α-reductase leads to a decrease, DHT levels |

High |

High (canonical) |

It is well established that 5α-reductase converts testosterone to DHT. In vitro, in vivo and human studies with 5α-reductase inhibitors have shown that the stressors dose-dependently decrease formation of DHT. |

|

KER-1935 Decrease, DHT levels leads to a decrease, AR activation |

High |

High (canonical) |

It is well established that DHT activates the AR. Direct evidence for this KER is not possible since KE 1614 can currently not be measured and is considered an in vivo effect. Indirect evidence using proxy read-outs of AR activation, either in vitro or in vivo, strongly supports the relationship. |

|

KER-2124 Decrease, AR activation leads to altered transcription of genes by AR |

High |

High (canonical) |

It is well established that the AR regulates gene transcription. In vivo animal studies and human genomic profiling show tissue-specific changes to gene expression upon disruption of AR. |

|

KER-3348 Decrease, AR activation leads to increase, nipple retention |

High |

High |

It is well established that activation of AR drives regression of nipple anlagen in males. The empirical evidence includes numerous in vivo toxicity studies showing that decreased AR activation leads to increased NR in male offspring, with few inconsistencies. The empirical evidence combined with theoretical considerations provide some support for dose, temporal, and incidence concordance for the KER, although this evidence is weak and indirect. |

Quantitative Consideration

The quantitative understanding of the AOP is limited. A key difficulty lies in the challenge of extrapolating from in vitro to in vivo events since these cannot be captured within the same experimental framework. Specifically, MIE-1617 is evaluated in vitro, while both KE-1613 (decrease, DHT levels’), KE-1614 (decrease, AR activation’) and the AO (Increase, NR) are in vivo endpoints. It should be noted that KE-1614 pertains to AR activation in vivo - currently lacking viable methods for direct measurement.

For in vivo to in vivo KERs like KER-1935 (‘Decrease, DHT level leads to Decrease, AR activation’) and KER-2124 (‘Decrease, AR activation leads to Altered, Transcription of genes by the AR’), there is not enough data to define a quantitative relationship, and such a relationship will differ between biological systems (species, tissue, cell type, life stage etc).

Considerations for Potential Applications of the AOP (optional)

The AOP supports the regulatory application of NR as a measure of endocrine disruption relevant for human health and the use of NR as an indicator of anti-androgenicity in mammals and other vertebrates in the environment.

NR is a mandatory endpoint in multiple OECD test guidelines, including TG 443 (extended one-generation reproductive toxicity study) and TGs 421/422 (reproductive toxicity screening studies) (OECD 2025a; OECD 2025b; OECD 2025c). NR can contribute to establishing a No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL), as outlined in OECD guidance documents No. 43 and 151 (OECD 2008; OECD 2013). The ability to derive a NOAEL for increased NR in male rodent offspring, which can serve as a point of departure for determining human safety thresholds, underscores the regulatory significance of this AOP.

The AOP also holds utility for informing on anti-androgenicity more generally, as this modality is highly relevant across mammalian species (Schwartz et al., 2021) and vertebrates more broadly due to the conserved nature of the AR and its implication in sexual differentiation across species (Ogino et al., 2023).

References

Aggarwal, S., Thareja, S., Verma, A., Bhardwaj, T. R., & Kumar, M. (2010). An overview on 5α-reductase inhibitors. Steroids, 75(2), 109–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2009.10.005

Amato, C. M., Yao, H. H.-C., & Zhao, F. (2022). One Tool for Many Jobs: Divergent and Conserved Actions of Androgen Signaling in Male Internal Reproductive Tract and External Genitalia. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.910964

Bologna, M., Muzi, P., Biordi, L., Festuccia, C., & Vicentini, C. (1995). Finasteride dose-dependently reduces the proliferation rate of the LnCap human prostatic cancer cell line in vitro. Urology, 45(2), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-4295(95)80019-0

Chamberlain, N. L., Driver, E. D., & Miesfeld, R. L. (1994). The length and location of CAG trinucleotide repeats in the androgen receptor N-terminal domain affect transactivation function. Nucleic Acids Research, 22(15), 3181–3186. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.15.3181

Christiansen S, Scholze M, Dalgaard M, Vinggaard AM, Axelstad M, Kortenkamp A, & Hass U. (2009). Synergistic disruption of external male sex organ development by a mixture of four antiandrogens. Environmental Health Perspectives, 117(12), 1839–1846. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0900689

Clark, R. V., Hermann, D. J., Cunningham, G. R., Wilson, T. H., Morrill, B. B., & Hobbs, S. (2004). Marked Suppression of Dihydrotestosterone in Men with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia by Dutasteride, a Dual 5α-Reductase Inhibitor. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 89(5), 2179–2184. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2003-030330

Davey, R. A., & Grossmann, M. (2016). Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. The Clinical Biochemist. Reviews, 36(4), 3–15.

Drake, L., Hordinsky, M., Fiedler, V., Swinehart, J., Unger, W. P., Cotterill, P. C., Thiboutot, D. M., Lowe, N., Jacobson, C., Whiting, D., Stieglitz, S., Kraus, S. J., Griffin, E. I., Weiss, D., Carrington, P., Gencheff, C., Cole, G. W., Pariser, D. M., Epstein, E. S., … Waldstreicher, J. (1999). The effects of finasteride on scalp skin and serum androgen levels in men with androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 41(4), 550–554.

Draskau, M. K., Rosenmai, A. K., Bouftas, N., Johansson, H. K. L., Panagiotou, E. M., Holmer, M. L., Elmelund, E., Zilliacus, J., Beronius, A., Damdimopoulou, P., van Duursen, M., & Svingen, T. (2024). AOP Report: An Upstream Network for Reduced Androgen Signaling Leading to Altered Gene Expression of Androgen Receptor–Responsive Genes in Target Tissues. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 43(11), 2329–2337. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5972

Goldman AS, Shapiro B, & Neumann F. (1976). Role of testosterone and its metabolites in the differentiation of the mammary gland in rats. Endocrinology, 99(6), 1490–1495. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-99-6-1490

Holmer ML, Zilliacus J, Draskau MK, Hlisníková H, Beronius A, Svingen T. Methodology for developing data-rich Key Event Relationships for Adverse Outcome Pathways exemplified by linking decreased androgen receptor activity with decreased anogenital distance. Reprod Toxicol. 2024 Sep;128:108662. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2024.108662 . Epub 2024 Jul 8. PMID: 38986849.

Imperato-McGinley J, Binienda Z, Gedney J, & Vaughan ED Jr. (1986). Nipple differentiation in fetal male rats treated with an inhibitor of the enzyme 5 alpha-reductase: definition of a selective role for dihydrotestosterone. Endocrinology, 118(1), 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-118-1-132

Knapczyk-Stwora, K., Nynca, A., Ciereszko, R. E., Paukszto, L., Jastrzebski, J. P., Czaja, E., Witek, P., Koziorowski, M., & Slomczynska, M. (2019). Flutamide-induced alterations in transcriptional profiling of neonatal porcine ovaries. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 10(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-019-0340-y

Kratochwil, K., & Schwartz, P. (1976). Tissue interaction in androgen response of embryonic mammary rudiment of mouse: identification of target tissue for testosterone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 73(11), 4041–4044. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.73.11.4041

Leung, J. K., & Sadar, M. D. (2017). Non-Genomic Actions of the Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00002

Mendonca, B. B., Batista, R. L., Domenice, S., Costa, E. M. F., Arnhold, I. J. P., Russell, D. W., & Wilson, J. D. (2016). Steroid 5α-reductase 2 deficiency. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 163, 206–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.05.020

OECD (2008), Guidance Document on Mammalian Reproductive Toxicity Testing and Assessment, OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 43, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d2631d22-en.

OECD (2013), Guidance Document Supporting OECD Test Guideline 443 on the Extended One-Generational Reproductive Toxicity Test, OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, No. 151, OECD Publishing, Paris, ENV/JM/MONO(2013)10

OECD. (2023). Test No. 458: Stably Transfected Human Androgen Receptor Transcriptional Activation Assay for Detection of Androgenic Agonist and Antagonist Activity of Chemicals. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264264366-en

OECD. (2025a). Test No. 421: Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264264380-en

OECD. (2025b). Test No. 422: Combined Repeated Dose Toxicity Study with the Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264264403-en

OECD. (2025c). Test No. 443: Extended One-Generation Reproductive Toxicity Study. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264185371-en

Ogino, Y., Ansai, S., Watanabe, E. et al. Evolutionary differentiation of androgen receptor is responsible for sexual characteristic development in a teleost fish. Nat Commun 14, 1428 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37026-6

Pedersen, E. B., Christiansen, S., & Svingen, T. (2022). AOP key event relationship report: Linking androgen receptor antagonism with nipple retention. In Current Research in Toxicology (Vol. 3). Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2022.100085

Robitaille, J., & Langlois, V. S. (2020). Consequences of steroid-5α-reductase deficiency and inhibition in vertebrates. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 290, 113400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2020.113400

Schwartz, C. L., Christiansen, S., Hass, U., Ramhøj, L., Axelstad, M., Löbl, N. M., & Svingen, T. (2021). On the Use and Interpretation of Areola/Nipple Retention as a Biomarker for Anti-androgenic Effects in Rat Toxicity Studies. In Frontiers in Toxicology (Vol. 3). Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/ftox.2021.730752

Svingen, T., Villeneuve, D. L., Knapen, D., Panagiotou, E. M., Draskau, M. K., Damdimopoulou, P., & O’Brien, J. M. (2021). A Pragmatic Approach to Adverse Outcome Pathway Development and Evaluation. Toxicological Sciences, 184(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfab113

Tut, T. G., Ghadessy, F. J., Trifiro, M. A., Pinsky, L., & Yong, E. L. (1997). Long Polyglutamine Tracts in the Androgen Receptor Are Associated with Reduced Trans -Activation, Impaired Sperm Production, and Male Infertility 1. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 82(11), 3777–3782. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.82.11.4385

Williams, A. J., Grulke, C. M., Edwards, J., McEachran, A. D., Mansouri, K., Baker, N. C., Patlewicz, G., Shah, I., Wambaugh, J. F., Judson, R. S., & Richard, A. M. (2017). The CompTox Chemistry Dashboard: a community data resource for environmental chemistry. Journal of Cheminformatics, 9(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-017-0247-6

Wolf, C., Lambright, C., Mann, P., Price, M., Cooper, R. L., Ostby, J., & Earl Gray, L. J. (1999). Administration of potentially antiandrogenic pesticides (procymidone, linuron, iprodione, chlozolinate, p,p-DDE, and ketoconazole) and toxic substances (dibutyl-and diethylhexyl phthalate, PCB 169, and ethane dimethane sulphonate) during sexual differentiation produces diverse profiles of reproductive malformations in the male rat. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 15, 94–118. www.stockton-press.co.uk

You, L., Casanova, M., Archibeque-Engle, S., Sar, M., Fan, L.-Q., & Heck, A. (1998). Impaired Male Sexual Development in Perinatal Sprague-Dawley and Long-Evans Hooded Rats Exposed in Utero and Lactationally to p,p’-DDE. In TOX1COLOGICAL SCIENCES (Vol. 45). https://academic.oup.com/toxsci/article/45/2/162/1653877

Appendix 1

List of MIEs in this AOP

Event: 1617: Inhibition, 5α-reductase

Short Name: Inhibition, 5α-reductase

AOPs Including This Key Event

| AOP ID and Name | Event Type |

|---|---|

| Aop:289 - Inhibition of 5α-reductase leading to impaired fecundity in female fish | MolecularInitiatingEvent |

| Aop:305 - 5α-reductase inhibition leading to short anogenital distance (AGD) in male (mammalian) offspring | MolecularInitiatingEvent |

| Aop:120 - Inhibition of 5α-reductase leading to Leydig cell tumors (in rat) | MolecularInitiatingEvent |

| Aop:571 - 5α-reductase inhibition leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring | MolecularInitiatingEvent |

| Aop:576 - 5α-reductase inhibition leading to increased nipple retention (NR) in male (rodent) offspring | MolecularInitiatingEvent |

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Molecular |

Cell term

| Cell term |

|---|

| eukaryotic cell |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mixed | High |

This KE is applicable to both sexes, across developmental stages into adulthood, in many different tissues and across mammalian taxa. It is, however, acknowledged that this KE most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to add additional relevant knowledge to expand on the applicability to also include other vertebrates.

Essentially the reaction performed by the isozymes is the same, but the enzyme is differentially expressed in the body. 5α-reductase type 1 is mainly linked to the production of neurosteroids, 5α-reductase type 2 is mainly involved in production of 5α-DHT, whereas 5α-reductase type 3 is involved in N-glycosylation (Robitaille & Langlois, 2020).

The expression profile of the three 5α-reductase isoforms depends on the developmental stage, the tissue of interest, and the disease state of the tissue. The enzymes have been identified in, for instance, non-genital and genital skin, scalp, prostate, liver, seminal vesicle, epididymis, testis, ovary, kidney, exocrine pancreas, and brain (Azzouni, 2012, Uhlen 2015).

5α-reductase is well-conserved, all primary species in Eukaryota contain all three isoforms (from plant, amoeba, yeast to vertebrates) (Azzouni, 2012) and the enzymes are expressed in both males and females (Langlois, 2010, Uhlen 2015).

Key Event Description

This KE describes the inhibition of 5α-reductases (3-oxo-5α-steroid 4-dehydrogenases). These enzymes are widely expressed in tissues of both sexes and responsible for conversion of steroid hormones.

There are three isozymes: 5α-reductase type 1, 2, and 3. The substrates for 5α-reductases are 3-oxo (3-keto), Δ4,5 C19/C21 steroids such as testosterone, progesterone, androstenedione, epi-testosterone, cortisol, aldosterone, and deoxycorticosterone. The enzymatic reaction leads to an irreversible breakage of the double bond between carbon 4 and 5 and subsequent insertion of a hydride anion at carbon 5 and insertion of a proton at carbon 4. The reaction is aided by the cofactor NADPH. The substrate affinity and reaction velocity differ depending on the combination of substrate and enzyme isoform, for instance 5α-reductase type 2 has a higher substrate affinity for testosterone than the type 1 isoform of the enzyme, and the enzymatic reaction occurs at a higher velocity under optimal conditions. Likewise, inhibitors of 5α-reductase may exhibit differential effects depending on isoforms (Azzouni et al., 2012).

How it is Measured or Detected

There is currently (as of 2023) no OECD test guideline for the measurement of 5α-reductase inhibition.

Assessing the ability of chemicals to inhibit the activity of 5α-reductase is challenging, but has been assessed using transfected cell lines. This has been demonstrated in HEK-293 cells stably transfected with human 5α-reductase type 1, 2, and 3 (Yamana et al., 2010), in CHO cells stably transfected with human 5α-reductase type 1 and 2 (Thigpens et al., 1993), and COS cells transfected with human and rat 5α-reductase with unspecified isoforms (Andersson & Russell, 1990). The transfected cells are typically used as intact cells or cell homogenates. Further, 5α-reductase 1 and 2 has been successfully expressed and isolated from Escherichia coli with subsequent functionality allowing for examination of enzyme inhibition (Peng et al., 2020). The availability of the stably transfected cell lines and the isolated enzymes to the scientific community is unknown.

The output of the above methods could be decreased dihydrotestosterone (DHT) with increasing test chemical concentrations. Other substrates exist for the different isoforms that could be used to assess the enzymatic inhibition (Peng et al., 2020). The use of radiolabeled steroids has historic and continued use for 5α-reductase inhibition examination (Andersson & Russell, 1990; Peng et al., 2020; Thigpens et al., 1993; Yamana et al., 2010); however, alternative methods are available, such as conventional ELISA kits or advanced analytical methods such as liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

References

Andersson, S., & Russell, D. W. (1990). Structural and biochemical properties of cloned and expressed human and rat steroid 5a-reductases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 3640–3644. https://www.pnas.org

Azzouni, F., Godoy, A., Li, Y., & Mohler, J. (2012). The 5 alpha-reductase isozyme family: A review of basic biology and their role in human diseases. In Advances in Urology. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/530121

Peng, H. M., Valentin-Goyco, J., Im, S. C., Han, B., Liu, J., Qiao, J., & Auchus, R. J. (2020). Expression in escherichia coli, purification, and functional reconstitution of human steroid 5α-reductases. Endocrinology (United States), 161(8), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1210/ENDOCR/BQAA117

Robitaille, J., & Langlois, V. S. (2020). Consequences of steroid-5α-reductase deficiency and inhibition in vertebrates. In General and Comparative Endocrinology (Vol. 290). Academic Press Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2020.113400

Thigpens, A. E., Cala, K. M., & Russell, D. W. (1993). Characterization of Chinese Hamster Ovary Cell Lines Expressing Human Steroid 5a-Reductase Isozymes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 268(23), 17404–17412.

Yamana, K., Fernand, L., Luu-The, V., & Luu-The, V. (2010). Human type 3 5α-reductase is expressed in peripheral tissues at higher levels than types 1 and 2 and its activity is potently inhibited by finasteride and dutasteride. Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation, 2(3), 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1515/HMBCI.2010.035

List of Key Events in the AOP

Event: 1613: Decrease, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels

Short Name: Decrease, DHT level

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| hormone biosynthetic process | 17beta-Hydroxy-2-oxa-5alpha-androstan-3-one | decreased |

AOPs Including This Key Event

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Tissue |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| All life stages | Moderate |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mixed | High |

This KE is applicable to both sexes, across developmental stages and adulthood, in many different tissues and across mammals.

In both humans and rodents, DHT is important for the in utero differentiation and growth of the prostate and male external genitalia (Azzouni et al., 2012; Gerald & Raj, 2022). Besides its critical role in development, DHT also induces growth of facial and body hair during puberty in humans (Azzouni et al., 2012).

In mammals, the role of DHT in females is less established (Swerdloff et al., 2017), however studies suggest that androgens are important in e.g. bone metabolism and growth, as well as female reproduction from follicle development to parturition (Hammes & Levin, 2019).

It is, however, acknowledged that this KE most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to add additional relevant knowledge to expand on the applicability to also include other vertebrates.

Key Event Description

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is an endogenous steroid hormone and a potent androgen. The level of DHT in tissue or blood is dependent on several factors, such as the synthesis, uptake/release, metabolism, and elimination from the system, which again can be dependent on biological compartment and developmental stage.

DHT is primarily synthesized from testosterone (T) via the irreversible enzymatic reaction facilitated by 5α-Reductases (5α-REDs) (Swerdloff et al., 2017). Different isoforms of this enzyme are differentially expressed in specific tissues (e.g. prostate, skin, liver, and hair follicles) at different developmental stages, and depending on disease status (Azzouni et al., 2012; Uhlén et al., 2015), which ultimately affects the local production of DHT.

An alternative (“backdoor”) pathway , exists for DHT formation that is independent of T and androstenedione as precursors. While first discovered in marsupials, the physiological importance of this pathway has now also been established in other mammals including humans (Renfree and Shaw, 2023). This pathway relies on the conversion of progesterone (P) or 17-OH-P to androsterone and then androstanediol through several enzymatic reactions and finally, the conversion of androstanediol into DHT probably by HSD17B6 (Miller & Auchus, 2019; Naamneh Elzenaty et al., 2022). The “backdoor” synthesis pathway is a result of an interplay between placenta, adrenal gland, and liver during fetal life (Miller & Auchus, 2019).

The conversion of T to DHT by 5α-RED in peripheral tissue is mainly responsible for the circulating levels of DHT, though some tissues express enzymes needed for further metabolism of DHT consequently leading to little release and contribution to circulating levels (Swerdloff et al.).

The initial conversion of DHT into inactive steroids is primarily through 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) and 3β-HSD in liver, intestine, skin, and androgen-sensitive tissues. The subsequent conjugation is mainly mediated by uridine 5´-diphospho (UDP)-glucuronyltransferase 2 (UGT2) leading to biliary and urinary elimination from the system. Conjugation also occurs locally to control levels of highly potent androgens (Swerdloff et al., 2017).

Disruption of any of the aforementioned processes may lead to decreased DHT levels, either systemically or at tissue level.

How it is Measured or Detected

Several methods exist for DHT identification and quantification, such as conventional immunoassay methods (ELISA or RIA) and advanced analytical methods as liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The methods can have differences in detection and quantification limits, which should be considered depending on the DHT levels in the sample of interest. Further, the origin of the sample (e.g. cell culture, tissue, or blood) will have implications for the sample preparation.

Conventional immunoassays have limitations in that they can overestimate the levels of DHT compared to levels determined by gas chromatography mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (Hsing et al., 2007; Shiraishi et al., 2008). This overestimation may be explained by lack of specificity of the DHT antibody used in the RIA and cross-reactivity with T in samples (Swerdloff et al., 2017).

Test guideline no. 456 (OECD 2023) uses a cell line, NCI-H295, capable of producing DHT at low levels. The test guideline is not validated for this hormone. Measurement of DHT levels in these cells require low detection and quantification limits. Any effect on DHT can be a result of many upstream molecular events that are specific for the NCI-H295 cells, and which may differ in other models for steroidogenesis.

References

Azzouni, F., Godoy, A., Li, Y., & Mohler, J. (2012). The 5 alpha-reductase isozyme family: A review of basic biology and their role in human diseases. In Advances in Urology. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/530121

Gerald, T., & Raj, G. (2022). Testosterone and the Androgen Receptor. In Urologic Clinics of North America (Vol. 49, Issue 4, pp. 603–614). W.B. Saunders. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2022.07.004

Hammes, S. R., & Levin, E. R. (2019). Impact of estrogens in males and androgens in females. In Journal of Clinical Investigation (Vol. 129, Issue 5, pp. 1818–1826). American Society for Clinical Investigation. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI125755

Hsing, A. W., Stanczyk, F. Z., Bélanger, A., Schroeder, P., Chang, L., Falk, R. T., & Fears, T. R. (2007). Reproducibility of serum sex steroid assays in men by RIA and mass spectrometry. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention, 16(5), 1004–1008. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0792

Miller, W. L., & Auchus, R. J. (2019). The “backdoor pathway” of androgen synthesis in human male sexual development. PLoS Biology, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000198

Naamneh Elzenaty, R., du Toit, T., & Flück, C. E. (2022). Basics of androgen synthesis and action. In Best Practice and Research: Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (Vol. 36, Issue 4). Bailliere Tindall Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2022.101665

OECD (2023), Test No. 456: H295R Steroidogenesis Assay, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264122642-en.

Renfree, M. B., and Shaw, G. (2023). The alternate pathway of androgen metabolism and window of sensitivity. J. Endocrinol., JOE-22-0296. doi:10.1530/JOE-22-0296.

Shiraishi, S., Lee, P. W. N., Leung, A., Goh, V. H. H., Swerdloff, R. S., & Wang, C. (2008). Simultaneous measurement of serum testosterone and dihydrotestosterone by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clinical Chemistry, 54(11), 1855–1863. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2008.103846

Swerdloff, R. S., Dudley, R. E., Page, S. T., Wang, C., & Salameh, W. A. (2017). Dihydrotestosterone: Biochemistry, physiology, and clinical implications of elevated blood levels. In Endocrine Reviews (Vol. 38, Issue 3, pp. 220–254). Endocrine Society. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2016-1067

Uhlén, M., Fagerberg, L., Hallström, B. M., Lindskog, C., Oksvold, P., Mardinoglu, A., Sivertsson, Å., Kampf, C., Sjöstedt, E., Asplund, A., Olsson, I. M., Edlund, K., Lundberg, E., Navani, S., Szigyarto, C. A. K., Odeberg, J., Djureinovic, D., Takanen, J. O., Hober, S., … Pontén, F. (2015). Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science, 347(6220). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260419

Event: 1614: Decrease, androgen receptor activation

Short Name: Decrease, AR activation

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| androgen receptor activity | androgen receptor | decreased |

AOPs Including This Key Event

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Tissue |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mixed | High |

This KE is considered broadly applicable across mammalian taxa as all mammals express the AR in numerous cells and tissues where it regulates gene transcription required for developmental processes and functions. It is, however, acknowledged that this KE most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to add additional relevant knowledge to expand on the applicability to also include other vertebrates.

Key Event Description

This KE refers to decreased activation of the androgen receptor (AR) as occurring in complex biological systems such as tissues and organs in vivo. It is thus considered distinct from KEs describing either blocking of AR or decreased androgen synthesis.

The AR is a nuclear transcription factor with canonical AR activation regulated by the binding of the androgens such as testosterone or dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Thus, AR activity can be decreased by reduced levels of steroidal ligands (testosterone, DHT) or the presence of compounds interfering with ligand binding to the receptor (Davey & Grossmann, 2016; Gao et al., 2005).

In the inactive state, AR is sequestered in the cytoplasm of cells by molecular chaperones. In the classical (genomic) AR signaling pathway, AR activation causes dissociation of the chaperones, AR dimerization and translocation to the nucleus to modulate gene expression. AR binds to the androgen response element (ARE) (Davey & Grossmann, 2016; Gao et al., 2005). Notably, for transcriptional regulation the AR is closely associated with other co-factors that may differ between cells, tissues and life stages. In this way, the functional consequence of AR activation is cell- and tissue-specific. This dependency on co-factors such as the SRC proteins also means that stressors affecting recruitment of co-activators to AR can result in decreased AR activity (Heinlein & Chang, 2002).

Ligand-bound AR may also associate with cytoplasmic and membrane-bound proteins to initiate cytoplasmic signaling pathways with other functions than the nuclear pathway. Non-genomic AR signaling includes association with Src kinase to activate MAPK/ERK signaling and activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Decreased AR activity may therefore be a decrease in the genomic and/or non-genomic AR signaling pathways (Leung & Sadar, 2017).

How it is Measured or Detected

This KE specifically focuses on decreased in vivo activation, with most methods that can be used to measure AR activity carried out in vitro. They provide indirect information about the KE and are described in lower tier MIE/KEs (see for example MIE/KE-26 for AR antagonism, KE-1690 for decreased T levels and KE-1613 for decreased dihydrotestosterone levels). Assays may in the future be developed to measure AR activation in mammalian organisms.

References

Davey, R. A., & Grossmann, M. (2016). Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. The Clinical Biochemist. Reviews, 37(1), 3–15.

Gao, W., Bohl, C. E., & Dalton, J. T. (2005). Chemistry and structural biology of androgen receptor. Chemical Reviews, 105(9), 3352–3370. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020456u

Heinlein, C. A., & Chang, C. (2002). Androgen Receptor (AR) Coregulators: An Overview. https://academic.oup.com/edrv/article/23/2/175/2424160

Leung, J. K., & Sadar, M. D. (2017). Non-Genomic Actions of the Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00002

OECD (2022). Test No. 251: Rapid Androgen Disruption Activity Reporter (RADAR) assay. Paris: OECD Publishing doi:10.1787/da264d82-en.

|

|

|

Event: 286: Altered, Transcription of genes by the androgen receptor

Short Name: Altered, Transcription of genes by the AR

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| regulation of gene expression | androgen receptor | decreased |

AOPs Including This Key Event

Stressors

| Name |

|---|

| Bicalutamide |

| Cyproterone acetate |

| Epoxiconazole |

| Flutamide |

| Flusilazole |

| Prochloraz |

| Propiconazole |

| Stressor:286 Tebuconazole |

| Triticonazole |

| Vinclozalin |

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Tissue |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mixed | High |

Both the DNA-binding and ligand-binding domains of the AR are highly evolutionary conserved, whereas the transactivation domain show more divergence, which may affect AR-mediated gene regulation across species (Davey and Grossmann 2016). Despite certain inter-species differences, AR function mediated through gene expression is highly conserved, with mutation studies from both humans and rodents showing strong correlation for AR-dependent development and function (Walters et al. 2010).

This KE is considered broadly applicable across mammalian taxa, sex and developmental stages, as all mammals express the AR in numerous cells and tissues where it regulates gene transcription required for developmental processes and function. It is, however, acknowledged that this KE most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to add additional relevant knowledge to expand on the applicability to also include other vertebrates.

Key Event Description

This KE refers to transcription of genes by the androgen receptor (AR) as occurring in complex biological systems such as tissues and organs in vivo. Rather than measuring individual genes, this KE aims to capture patterns of effects at transcriptome level in specific target cells/tissues. In other words, it can be replaced by specific KEs for individual adverse outcomes as information becomes available, for example the transcriptional toxicity response in prostate tissue for AO: prostate cancer, perineum tissue for AO: reduced AGD, etc. AR regulates many genes that differ between tissues and life stages and, importantly, different gene transcripts within individual cells can go in either direction since AR can act as both transcriptional activator and suppressor. Thus, the ‘directionality’ of the KE cannot be either reduced or increased, but instead describe an altered transcriptome.

The Androgen Receptor and its function

The AR belongs to the steroid hormone nuclear receptor family. It is a ligand-activated transcription factor with three domains: the N-terminal domain, the DNA-binding domain, and the ligand-binding domain with the latter being the most evolutionary conserved (Davey and Grossmann 2016). Androgens (such as dihydrotestosterone and testosterone) are AR ligands and act by binding to the AR in androgen-responsive tissues (Davey and Grossmann 2016). Human AR mutations and mouse knockout models have established a fundamental role for AR in masculinization and spermatogenesis (Maclean et al.; Walters et al. 2010; Rana et al. 2014). The AR is also expressed in many other tissues such as bone, muscles, ovaries and within the immune system (Rana et al. 2014).

Altered transcription of genes by the AR as a Key Event

Upon activation by ligand-binding, the AR translocates from the cytoplasm to the cell nucleus, dimerizes, binds to androgen response elements in the DNA to modulate gene transcription (Davey and Grossmann 2016). The transcriptional targets vary between cells and tissues, as well as with developmental stages and is also dependent on available co-regulators (Bevan and Parker 1999; Heemers and Tindall 2007). It should also be mentioned that the AR can work in other ‘non-canonial’ ways such as non-genomic signaling, and ligand-independent activation (Davey & Grossmann, 2016; Estrada et al, 2003; Jin et al, 2013).

A large number of known, and proposed, target genes of AR canonical signaling have been identified by analysis of gene expression following treatments with AR agonists (Bolton et al. 2007; Ngan et al. 2009, Jin et al. 2013).

How it is Measured or Detected

Altered transcription of genes by the AR can be measured by measuring the transcription level of known downstream target genes by RT-qPCR or other transcription analyses approaches, e.g. transcriptomics.

Since this KE aims to capture AR-mediated transcriptional patterns of effect, downstream bioinformatics analyses will typically be required to identify and compare effect footprints. Clusters of genes can be statistically associated with, for example, biological process terms or gene ontology terms relevant for AR-mediated signaling. Large transcriptomics data repositories can be used to compare transcriptional patterns between chemicals, tissues, and species (e.g. TOXsIgN (Darde et al, 2018a; Darde et al, 2018b), comparisons can be made to identified sets of AR ‘biomarker’ genes (e.g. as done in (Rooney et al, 2018)), and various methods can be used e.g. connectivity mapping (Keenan et al, 2019).

References

Bevan C, Parker M (1999) The role of coactivators in steroid hormone action. Exp. Cell Res. 253:349–356

Bolton EC, So AY, Chaivorapol C, et al (2007) Cell- and gene-specific regulation of primary target genes by the androgen receptor. Genes Dev 21:2005–2017. doi: 10.1101/gad.1564207

Darde, T. A., Gaudriault, P., Beranger, R., Lancien, C., Caillarec-Joly, A., Sallou, O., et al. (2018a). TOXsIgN: a cross-species repository for toxicogenomic signatures. Bioinformatics 34, 2116–2122. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty040.

Darde, T. A., Chalmel, F., and Svingen, T. (2018b). Exploiting advances in transcriptomics to improve on human-relevant toxicology. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 11–12, 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.cotox.2019.02.001.

Davey RA, Grossmann M (2016) Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. Clin Biochem Rev 37:3–15

Estrada M, Espinosa A, Müller M, Jaimovich E (2003) Testosterone Stimulates Intracellular Calcium Release and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases Via a G Protein-Coupled Receptor in Skeletal Muscle Cells. Endocrinology 144:3586–3597. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0164

Heemers H V., Tindall DJ (2007) Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: A diversity of functions converging on and regulating the AR transcriptional complex. Endocr. Rev. 28:778–808

Jin, Hong Jian, Jung Kim, and Jindan Yu. 2013. “Androgen Receptor Genomic Regulation.” Translational Andrology and Urology 2(3):158–77. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2013.09.01

Keenan, A. B., Wojciechowicz, M. L., Wang, Z., Jagodnik, K. M., Jenkins, S. L., Lachmann, A., et al. (2019). Connectivity Mapping: Methods and Applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2, 69–92. doi:10.1146/ANNUREV-BIODATASCI-072018-021211.

Maclean HE, Chu S, Warne GL, Zajact JD Related Individuals with Different Androgen Receptor Gene Deletions

MacLeod DJ, Sharpe RM, Welsh M, et al (2010) Androgen action in the masculinization programming window and development of male reproductive organs. In: International Journal of Andrology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp 279–287

Ngan S, Stronach EA, Photiou A, et al (2009) Microarray coupled to quantitative RT–PCR analysis of androgen-regulated genes in human LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 28:2051–2063. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.68

Rana K, Davey RA, Zajac JD (2014) Human androgen deficiency: Insights gained from androgen receptor knockout mouse models. Asian J. Androl. 16:169–177

Rooney, J. P., Chorley, B., Kleinstreuer, N., and Corton, J. C. (2018). Identification of Androgen Receptor Modulators in a Prostate Cancer Cell Line Microarray Compendium. Toxicol. Sci. 166, 146–162. doi:10.1093/TOXSCI/KFY187.

Walters KA, Simanainen U, Handelsman DJ (2010) Molecular insights into androgen actions in male and female reproductive function from androgen receptor knockout models. Hum Reprod Update 16:543–558. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq003

List of Adverse Outcomes in this AOP

Event: 1786: Nipple retention (NR), increased

Short Name: nipple retention, increased

AOPs Including This Key Event

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Individual |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability Life Stage Applicability| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Birth to < 1 month | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

The applicability domain of NR is limited to male laboratory strains of rats and mice from birth to juvenile age.

Key Event Description

In common laboratory strains of rats and mice, females typically have 6 (rats) or 5 (mice) pairs of nipples along the bilateral milk lines. In contrast, male rats and mice do not have nipples. This is unlike e.g., humans where both sexes have 2 nipples (Schwartz et al., 2021).

In laboratory rats, high levels of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) induce regression of the nipples in males (Imperato-McGinley & Gautier, 1986; Kratochwil, 1977; Kratochwil & Schwartz, 1976). Females, in the absence of this DHT surge, retain their nipples. This relationship has also been shown in numerous rat studies with perinatal exposure to anti-androgenic chemicals (Schwartz et al., 2021). Hence, if juvenile male rats and mice possess nipples, it is considered a sign of perturbed androgen action early in life.

This KE was first published by Pedersen et al (2022).

How it is Measured or Detected

Nipple retention (NR) is visually assessed, ideally on postnatal day (PND) 12/13 (OECD, 2018; Schwartz et al., 2021). However, PND 14 is also an accepted stage of examination (OECD, 2013). Depending on animal strain, the time when nipples become visible can vary, but the assessment of NR in males should be conducted when nipples are visible in their female littermates (OECD, 2013).

Nipples are detected as dark spots (or shadows) called areolae, which resemble precursors to a nipple rather than a fully developed nipple. The dark area may or may not display a nipple bud (Hass et al., 2007). Areolae typically emerge along the milk lines of the male pups corresponding to where female pups display nipples. Fur growth may challenge detection of areolae after PND 14/15. Therefore, the NR assessment should be conducted prior to excessive fur growth. Ideally, all pups in a study are assessed on the same postnatal day to minimize variation due to maturation level (OECD, 2013).

NR is occasionally observed in controls. Hence, accurate assessment of NR in controls is needed to detect substance-induced effects on masculine development (Schwartz et al., 2021). It is recommended by the OECD guidance documents 43 and 151 to record NR as a quantitative number rather than a qualitative measure (present/absent or yes/no response). This allows for more nuanced analysis of results, e.g., high control values may be recognized (OECD, 2013, 2018). Studies reporting quantitative measures of NR are therefore considered stronger in terms of weight of evidence.

Reproducibility of NR results is challenged by the measure being a visual assessment prone to a degree of subjectivity. Thus, NR should be assessed and scored blinded to exposure groups and ideally be performed by the same person(s) within the same study.

Regulatory Significance of the AO

NR is recognized by the OECD as a relevant measure for anti-androgenic effects and is mandatory in the test guidelines Extended One Generation Reproductive Toxicity Study, TG 443 (OECD, 2018) and the two screening studies for reproductive toxicity, TGs 421/422 (OECD, 2016a, 2016b). The endpoint is also described in the guidance documents 43 (OECD, 2008) and 151 (OECD, 2013). Furthermore, NR data can be used in chemical risk assessment for setting the No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) as stated in the OECD guidance document 151 (OECD, 2013): “A statistically significant change in nipple retention should be evaluated similarly to an effect on AGD as both endpoints indicate an adverse effect of exposure and should be considered in setting a NOAEL”.

References

Hass, U., Scholze, M., Christiansen, S., Dalgaard, M., Vinggaard, A. M., Axelstad, M., Metzdorff, S. B., & Kortenkamp, A. (2007). Combined exposure to anti-androgens exacerbates disruption of sexual differentiation in the rat. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115(suppl 1), 122–128.

Imperato-McGinley, J., Binienda, Z., Gedney, J., & Vaughan, E. D. (1986). Nipple Differentiation in Fetal Male Rats Treated with an Inhibitor of the Enzyme 5α-Reductase: Definition of a Selective Role for Dihydrotestosterone. Endocrinology, 118(1), 132–137.

Kratochwil, K. (1977). Development and Loss of Androgen Responsiveness in the Embryonic Rudiment of the Mouse Mammary Gland. DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY, 61, 358–365.

OECD. (2008). Guidance document 43 on mammalian reproductive toxicity testing and assessment. Environment, Health and Safety Publications, 16(43).

OECD. (2013). Guidance document supporting OECD test guideline 443 on the extended one-generation reproductive toxicity test. Environment, Health and Safety Publications, 10(151).

OECD. (2016a). Test Guideline 421: Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, 421. http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions/

OECD. (2016b). Test Guideline 422: Combined Repeated Dose Toxicity Study with the Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, 422. http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions/

OECD. (2018). Test Guideline 443: Extended one-generation reproductive toxicity study. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, 443. http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions/

Pedersen, E. B., Christiansen, S., & Svingen, T. (2022). AOP key event relationship report: Linking androgen receptor antagonism with nipple retention. Current Research in Toxicology, 3, 100085.

Schwartz, C. L., Christiansen, S., Hass, U., Ramhøj, L., Axelstad, M., Löbl, N. M., & Svingen, T. (2021). On the Use and Interpretation of Areola/Nipple Retention as a Biomarker for Anti-androgenic Effects in Rat Toxicity Studies. Frontiers in Toxicology, 3, 730752.

Appendix 2

List of Key Event Relationships in the AOP

List of Adjacent Key Event Relationships

Relationship: 1880: Inhibition, 5α-reductase leads to Decrease, DHT level

AOPs Referencing Relationship

| AOP Name | Adjacency | Weight of Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of 5α-reductase leading to impaired fecundity in female fish | adjacent | High | High |

| 5α-reductase inhibition leading to short anogenital distance (AGD) in male (mammalian) offspring | adjacent | High | High |

| 5α-reductase inhibition leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring | adjacent | ||

| 5α-reductase inhibition leading to increased nipple retention (NR) in male (rodent) offspring | adjacent | High |

Evidence Supporting Applicability of this Relationship

| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mixed | High |

This KE is applicable for both sexes, across developmental stages into adulthood, in numerous cells and tissues and across mammalian taxa. It is, however, acknowledged that this KER most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to add additional relevant knowledge to expand on the applicability to also include other vertebrates.

Key Event Relationship Description

This key event relationship (KER) links inhibition of 5α-reductase activity to decreased dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels.

There are three isozymes of 5α-reductase: type 1, 2, and 3. 5α-reductase type 2 is mainly involved in the synthesis of 5α-DHT from testosterone (T) (Robitaille & Langlois, 2020), although 5α-reductase type 1 can also facilitate this reaction, but with lower affinity for T (Nikolaou et al., 2021). The type 1 isoform is also involved in the alternative (‘backdoor’) pathway for DHT formation, facilitating the conversion of progesterone or 17OH-progesterone to dihydroprogesterone or 5α-pregnan-17α-ol-3,20-dione, respectively, whereafter several subsequent reactions will ultimately lead to the formation of DHT (Miller & Auchus, 2019). The quantitative importance of the alternative pathway remains unclear (Alemany, 2022). The type 1 and type 2 isoforms of 5α-reductase are the primary focus of this KER.

The direct conversion of T to 5α-DHT mainly takes place in the target tissue (Robitaille & Langlois, 2020). In mammals, the type 1 isoform is found in the scalp and other peripheral tissues (Miller & Auchus, 2011), such as liver, skin, prostate (Azzouni et al., 2012), bone, ovaries, and adipose tissue (Nikolaou et al., 2021). The type 2 isoform is expressed mainly in male reproductive tissues (Miller & Auchus, 2011), but also in liver, scalp and skin (Nikolaou et al., 2021). The expression level of both isoforms depend on the developmental stage and the tissue.

Evidence Supporting this KER

Biological PlausibilityThe biological plausibility of this KER is considered high.

5α-reductase can catalyze the conversion of T to DHT. The substrates for 5α-reductases are 3-oxo (3-keto), Δ4,5 C19/C21 steroids such as testosterone and progesterone. The enzymatic reaction leads to an irreversible breakage of the double bond between carbon 4 and 5 and subsequent insertion of a hydride anion at carbon 5 and insertion of a proton at carbon 4. The reaction is aided by the cofactor NADPH (Azzouni et al., 2012). By inhibiting this enzyme, the described catalyzed reaction will be inhibited leading to a decrease in DHT levels.

In both humans and rodents, DHT is important for the in utero differentiation and growth of the prostate and male external genitalia. Besides its critical role during fetal development, DHT also induces growth of facial and body hair during puberty in humans (Azzouni et al., 2012).

Empirical EvidenceThe empirical evidence for this KER is considered high

Dose concordance

Several inhibitors of 5α-reductases have been developed for pharmacological uses. Inhibition of the enzymatic conversion of radiolabeled substrate has been illustrated (Table 1) and data display dose-concordance, with increasing concentrations of inhibitor leading to lower 5α-reductase product formation. These studies at large rely on conversion of radiolabeled substrate and hence serve as an indirect measurement.

Table 1: Dose concordance from selected in vitro test systems

|

Test system |

Model description |

Stressor |

Effect |

Reference |

|

HEK-293 cells |

Cells stably transfected human 5α-reductase type 1 and 2 used to measure conversion of [14C]labeled steroids |

Finasteride |

Type 1: IC50 = 106.9 µM Type 2: IC50 = 14.3 µM |

(Yamana et al., 2010) |

| Dutasteride |

Type 1: IC50 = 8.7 µM Type 2: IC50 = 57 µM |

|||

|

COS cells |

Cell homogenates from transfected cells with human and rat 5α-reductase (unknown isoform) used to measure conversion of radiolabeled testosterone |

Finasteride

|

Human: IC50 ≈ 1 µM Ki = 340-620 nM Rat: IC50 ≈ 0.1 µM Ki = 3-5 nM |

(Andersson & Russell, 1990) |

| 4-MA |

Human: IC50 ≈ 0.1 µM Ki = 7-8 nM Rat: IC50 ≈ 0.1 µM Ki = 5-7 nM |

|||

|

CHO cells |

Stably transfected with human 5α-reductase type 1 and 2 |

Finasteride

|

Type 1: Ki = 325 nM Type 2: Ki = 12 nM |

(Thigpens et al., 1993) |

| 4-MA |

Type 1: Ki = 8 nM Type 2: Ki = 4 nM |

|||

|

Isolated enzyme |

Human 5α-reductase type 1 and 2 used to measure conversion of radiolabeled substrate of both isoforms |

Finasteride |

Type 1: Ki = > 200 nM Type 2: Ki = 0.45 nM |

(Peng et al., 2020)

|

| Dutasteride |

Type 1: Ki = 39 nM Type 2: Ki = 1.1 nM |

These in vitro studies clearly show effects on the enzymatic reaction induced by 5α-reductases in a concentration dependent manner (Andersson & Russell, 1990; Thigpens et al., 1993; Yamana et al., 2010).

In the intact organism, when 5α-reductase type 2 activity is lacking through e.g. inhibitor treatment or knockout, this will results in decreased 5α-DHT locally in the tissues, but also in blood (Robitaille & Langlois, 2020). This has been demonstrated in humans, rats, monkeys, and mice (Robitaille et al. 2020).

Finasteride is a specific inhibitor of 5α-reductase type 2 (Russell & Wilson, 1994). Men with androgenic alopecia were treated with increasing concentrations of finasteride and presented with decreased DHT levels in biopsies from scalp, as well as a decrease in serum DHT levels with dose dependency being most apparent in serum, up to about 70% decrease (Drake et al., 1999). Likewise, men treated with dutasteride exhibited a clear dose dependent decrease in serum DHT after 24 weeks treatment with a maximum efficacy of about 98% (Clark et al., 2004).

Other evidence

The phenotype of males with deficiency in 5α-reductases are typically born with ambiguous external genitalia. They also present with small prostate, minimal facial hair and acne, or temporal hair loss. Comparison of affected individuals to non-affected individuals in regard to T/DHT ratio, conversion of infused radioactive T, and ratios of urinary metabolites of 5α-reductase and 5β-reductase concluded that these phenotypic characteristics were due to 5α-reductase defects that resulted in less conversion of T to DHT (Okeigwe et al. 2014). Mutations in the 5α-reductase gene can result in boys being born with moderate to severe undervirilization phenotypes (Elzenaty 2022).

Quantitative Understanding of the Linkage

Inhibitors of 5α-reductase are important for the prevention and treatment of many diseases. There are several compounds that have been developed for pharmaceutical purposes and they can target the different isoforms with different affinity. Examples of inhibitors are finasteride and dutasteride. Finasteride mainly has specificity for the type 2 isoform, whereas dutasteride inhibits both type 1 and 2 isoforms (Miller & Auchus, 2011).

These differences in isoform specificity reflects in the effects on DHT serum levels, hence the broader specificity of dutasteride leads to > 90% decrease in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia, in comparison to 70% with finasteride administration (Nikolaou et al., 2021).

Response-response relationshipEnzyme inhibition can occur in different ways e.g. both competitive and noncompetitive. The inhibition model depends on the specific inhibitor and hence a generic quantitative response-response relationship is difficult to derive.

Time-scaleAn inhibition of 5α-reductases would lead to an immediate change in DHT levels at the molecular level. However, the time-scale for systemic effects on hormone levels are challenging to estimate.

Known Feedforward/Feedback loops influencing this KERAndrogens can regulate gene expression of 5α-reductases (Andersson et al., 1989; Berman & Russell, 1993).

References

Alemany, M. (2022). The Roles of Androgens in Humans: Biology, Metabolic Regulation and Health. In International Journal of Molecular Sciences (Vol. 23, Issue 19). MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911952

Andersson, S., Bishop, R. W., & Russell$, D. W. (1989). THE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY Expression Cloning and Regulation of Steroid 5cw-Reductase, an Enzyme Essential for Male Sexual Differentiation* (Vol. 264, Issue 27).

Andersson, S., & Russell, D. W. (1990). Structural and biochemical properties of cloned and expressed human and rat steroid 5a-reductases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 3640–3644. https://www.pnas.org

Azzouni, F., Godoy, A., Li, Y., & Mohler, J. (2012). The 5 alpha-reductase isozyme family: A review of basic biology and their role in human diseases. In Advances in Urology. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/530121

Berman, D. M., & Russell, D. W. (1993). Cell-type-specific expression of rat steroid 5a-reductase isozymes (sexual development/androgens/prostate/stroma/epithelium). In Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (Vol. 90). https://www.pnas.org

Clark, R. V., Hermann, D. J., Cunningham, G. R., Wilson, T. H., Morrill, B. B., & Hobbs, S. (2004). Marked Suppression of Dihydrotestosterone in Men with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia by Dutasteride, a Dual 5α-Reductase Inhibitor. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 89(5), 2179–2184. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2003-030330

Drake, L., Hordinsky, M., Fiedler, V., Swinehart, J., Unger, W. P., Cotterill, P. C., Thiboutot, D. M., Lowe, N., Jacobson, C., Whiting, D., Stieglitz, S., Kraus, S. J., Griffin, E. I., Weiss, D., Carrington, P., Gencheff, C., Cole, G. W., Pariser, D. M., Epstein, E. S., … City, O. (1999). The effects of finasteride on scalp skin and serum androgen levels in men with androgenetic alopecia.

Miller, W. L., & Auchus, R. J. (2011). The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocrine Reviews, 32(1), 81–151. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2010-0013

Miller, W. L., & Auchus, R. J. (2019). The “backdoor pathway” of androgen synthesis in human male sexual development. PLoS Biology, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000198

Nikolaou, N., Hodson, L., & Tomlinson, J. W. (2021). The role of 5-reduction in physiology and metabolic disease: evidence from cellular, pre-clinical and human studies. In Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (Vol. 207). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105808

Peng, H. M., Valentin-Goyco, J., Im, S. C., Han, B., Liu, J., Qiao, J., & Auchus, R. J. (2020). Expression in escherichia coli, purification, and functional reconstitution of human steroid 5α-reductases. Endocrinology (United States), 161(8), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1210/ENDOCR/BQAA117

Robitaille, J., & Langlois, V. S. (2020). Consequences of steroid-5α-reductase deficiency and inhibition in vertebrates. In General and Comparative Endocrinology (Vol. 290). Academic Press Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2020.113400

Russell, D. W., & Wilson, J. D. (1994). STEROID Sa-REDUCTASE: TWO GENES/TWO ENZYMES. www.annualreviews.org

Thigpens, A. E., Cala, K. M., & Russell, D. W. (1993). Characterization of Chinese Hamster Ovary Cell Lines Expressing Human Steroid 5a-Reductase Isozymes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 268(23), 17404–17412.

Yamana, K., Fernand, L., Luu-The, V., & Luu-The, V. (2010). Human type 3 5α-reductase is expressed in peripheral tissues at higher levels than types 1 and 2 and its activity is potently inhibited by finasteride and dutasteride. Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation, 2(3), 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1515/HMBCI.2010.035

Relationship: 1935: Decrease, DHT level leads to Decrease, AR activation

AOPs Referencing Relationship

| AOP Name | Adjacency | Weight of Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of 17α-hydrolase/C 10,20-lyase (Cyp17A1) activity leads to birth reproductive defects (cryptorchidism) in male (mammals) | adjacent | High | High |

| 5α-reductase inhibition leading to short anogenital distance (AGD) in male (mammalian) offspring | adjacent | High | |

| 5α-reductase inhibition leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring | adjacent | ||

| 5α-reductase inhibition leading to increased nipple retention (NR) in male (rodent) offspring | adjacent | High |

Evidence Supporting Applicability of this Relationship

| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mixed | High |

Taxonomic applicability

KER1935 is assessed applicable to mammals, as DHT and AR activation are known to be related in mammals. It is, however, acknowledged that this KER most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to add additional relevant knowledge to expand on the applicability to also include other vertebrates.

Sex applicability

KER1935 is assessed applicable to both sexes, as DHT activates AR in both males and females.

Life-stage applicability

KER1935 is considered applicable to developmental and adult life stages, as DHT-mediated AR activation is relevant from the AR is expressed.

Key Event Relationship Description

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is a primary ligand for the Androgen receptor (AR), a nuclear receptor and transcription factor. DHT is an endogenous sex hormone that is synthesized from e.g. testosterone by the enzyme 5α-reductase in different tissues and organs (Davey & Grossmann, 2016; Marks, 2004). In the absence of ligand (e.g. DHT) the AR is localized in the cytoplasm in complex with molecular chaperones. Upon ligand binding, AR is activated, translocated into the nucleus, and dimerizes to carry out its ‘genomic function’ (Davey & Grossmann, 2016). Hence, AR transcriptional function is directly dependent on the presence of ligands, with DHT being a more potent AR activator than testosterone (Grino et al, 1990). Reduced levels of DHT may thus lead to reduced AR activation. Besides its genomic actions, the AR can also mediate rapid, non-genomic second messenger signaling (Davey and Grossmann, 2016). Decreased DHT levels that lead to reduced AR activation can thus entail downstream effects on both genomic and non-genomic signaling.

Evidence Supporting this KER

Biological PlausibilityThe biological plausibility of KER1935 is considered high.

The activation of AR is dependent on binding of ligands (though a few cases of ligand-independent AR activation has been shown, see uncertainties and inconsistencies), primarily testosterone and DHT in mammals (Davey and Grossmann, 2016; Schuppe et al., 2020). Without ligand activation, the AR will remain in the cytoplasm associated with heat-shock and other chaperones and not be able to carry out its canonical (‘genomic’) function. Upon androgen binding, the AR undergoes a conformational change, chaperones dissociate, and a nuclear localization signal is exposed. The androgen/AR complex can now translocate to the nucleus, dimerize and bind AR response elements to regulate target gene expression (Davey and Grossmann, 2016; Eder et al., 2001). AR transcriptional activity and specificity is regulated by co-activators and co-repressors in a cell-specific manner (Heinlein and Chang, 2002).

The requirement for androgens binding to the AR for transcriptional activity has been extensively studied and proven and is generally considered textbook knowledge. The OECD test guideline no. 458 uses DHT as the reference chemical for testing androgen receptor activation in vitro (OECD, 2020). In the absence of DHT during development caused by 5α-reductase deficiency (i.e. still in the presence of testosterone) male fetuses fail to masculinize properly. This is evidenced by, for instance, individuals with congenital 5α-reductase deficiency conditions (Costa et al., 2012); conditions not limited to humans (Robitaille and Langlois, 2020), testifying to the importance of specifically DHT for AR activation and subsequent masculinization of certain reproductive tissues.

Binding of testosterone or DHT has differential effects in different tissues. E.g. in the developing mammalian male; testosterone is required for development of the internal sex organs (epididymis, vas deferens and the seminal vesicles), whereas DHT is crucial for development of the external sex organs (Keller et al., 1996; Robitaille and Langlois, 2020).

Empirical EvidenceThe empirical support for KER1935 is considered high.

Dose concordance:

- Increasing concentrations of DHT lead to increasing AR activation in vitro in AR reporter gene assays (OECD, 2020; Williams et al., 2017).

Indirect (supporting) evidence: