AOP ID and Title:

Graphical Representation

Status

| Author status | OECD status | OECD project | SAAOP status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under Development: Contributions and Comments Welcome | Under Development | 1.105 | Included in OECD Work Plan |

Abstract

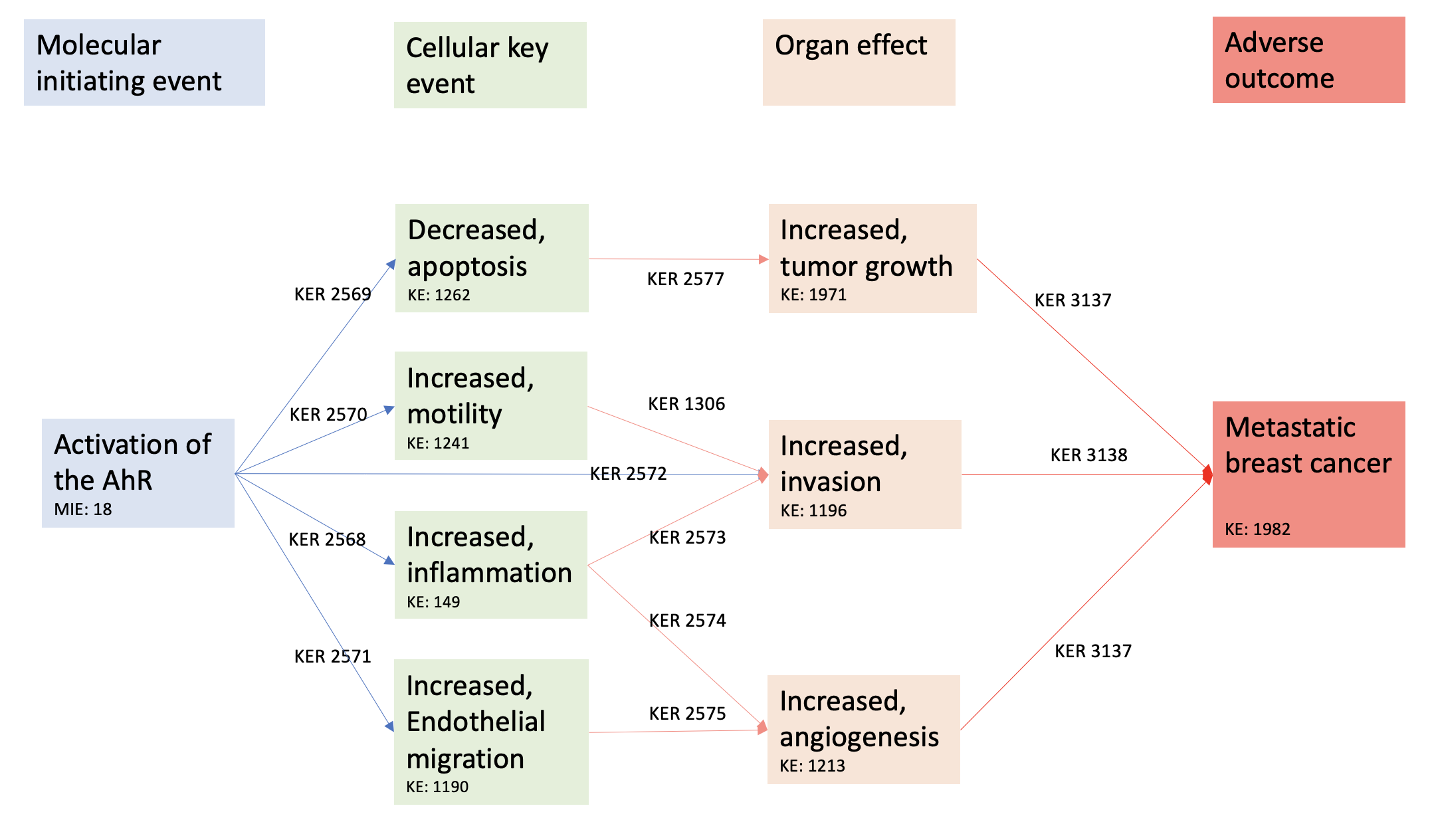

Breast cancer is the deadliest cancer in women with a poor prognosis in case of metastatic breast cancer. The role of the environments in the formation of metastasis has been suggested. We hypothesized that activation of the AhR (MIE), a xenobiotic receptor, could lead to breast cancer metastasis (AO), through different KEs, constituting a new AOP.

An artificial intelligence tool (AOP-helpfinder), which screens the available literature, was used to collect all existing scientific abstracts to build a novel AOP, using a list of key words. Four hundred and seven abstracts were found containing at least a word from our MIE list and either one word from our AO or KE list. A manual curation retained 113 pertinent articles, which were also screened using PubTator. From these analyses, an AOP was created linking the activation of the AhR to breast cancer related death through decreased apoptosis, inflammation, endothelial cell migration, and increased mortality. These KEs promote an increased tumor growth, angiogenesis and invasion which leads to breast cancer metastasis.

The evidence of the proposed AOP was weighted using the tailored Bradford Hill criteria and the AOP developers’ handbook (https://aopwiki.org/handbooks/). The confidence in our AOP and the biological plausibility was considered strong. Indeed, in vitro and in vivo findings on multiple types of breast cancers (with or without oesrtogen receptors, for instanace) supported our proposed AOP. An in vitro validation must be carried out, but our review proposes a strong relationship between AhR activation and breast cancer metastasis with an innovative use of an artificial intelligence literature search.

This work was published in Envionnmental International: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107323

Background

Breast cancer is a frequent disease, responsible of 2 262 419 new cases and 684 996 deaths in 2020 in the world, making it the deadliest female cancer (Bray et al., 2018). In 70% of cases, the disease is localized, and the prognosis is favorable with a 5-year survival of 99%. However, once the disease spreads (lymph nodes, metastasis), survival is severely altered with a 5-year survival rate of 26% in case of metastasis (Henley et al., 2020). It is therefore of paramount importance to understand the mechanisms of metastasis in breast cancer.

Amongst risk factors clearly established, including obesity, genetic mutations and hormonal exposure, the importance of the role of the environment is currently emerging (Koual et al., 2020 Nov 17). In an epidemiologic study, we found a positive association between the concentrations of 2.3.7.8-TCDD (2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxine) in the adipose tissue surrounding the tumors, and breast cancer metastasis in overweight and obese patients (Koual et al., 2019). Moreover, we have shown that, using both in vivo and in vitro models, TCDD exposure could promote an aggressive phenotype to breast cancer cells, thus favoring the formation of metastatic cells (Koual et al., 2021). TCDD is a potent ligand of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a transcriptional factor involved notably in the metabolism of xenobiotics (Larigot et al., 2022). Hence, the impact of the environment on breast cancer aggressiveness could be mediated by the activation of the AhR.

Interest is growing on the role of the AhR in breast cancer. First, the AhR is often overexpressed in different breast cancer cell lines (Zudaire et al., 2008, Kim et al., 2000 Nov 16, Li et al., 2014). Interestingly, the level of expression can be correlated to the stage or the molecular sub-type of the disease (Zudaire et al., 2008, Zhao et al., 2013). Second, the AhR pathway has been associated with different pro-metastatic features in breast cancer, such as resistance to apoptosis, invasiveness, modified cell cycle, migration and proliferation (Zudaire et al., 2008, Goode et al., 2013 Dec 15, Kanno et al., 2006). Triple negative cell lines, breast cancer cell lines with the worse prognosis (not over-expressing Her2 receptor or hormonal receptors), over-expressing the AhR seem to develop stem-like characteristics, favoring epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and thus metastasis (Stanford et al., 2016). Thirdly, the AhR could be involved in the resistance of breast cancer to treatments (Goode et al., 2013 Dec 15, Goode et al., 2014): after AhR knockout, Goode et al. found enhanced sensitivity of paclitaxel (a drug targeting cancer cells) in triple negative breast cancer, a cancer particularly difficult to treat (Goode et al., 2014). Breast cancer patients expressing estrogen receptors (ER-positive) in their cancer cells, can benefit from an efficient endocrine therapy, which greatly improves their survival. Activation of the AhR can lead to the loss of expression of the ER alpha and therefore to the loss of a potential therapeutic target (Safe et al., 2000 Jul).

The mechanisms linking the activation of the AhR to breast cancer aggressiveness are still unclear. Based on the AOP-wiki database (https://aopwiki.org/, last accessed March 2022), the central repository for AOPs, the AhR has already been proposed in several AOPs, but never in one characterized by the AO breast cancer metastasis. Likewise, an AOP linking an MIE to breast cancer aggressiveness has never been proposed. From our expertise and available knowledge, we hypothesize that the activation of the AhR could be a MIE leading to breast cancer metastasis (AO) through different KEs and KERs.

Summary of the AOP

Events

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE), Key Events (KE), Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Sequence | Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIE | 18 | Activation, AhR | Activation, AhR | |

| KE | 149 | Increase, Inflammation | Increase, Inflammation | |

| KE | 1262 | Apoptosis | Apoptosis | |

| KE | 1241 | Increased, Motility | Increased, Motility | |

| KE | 1190 | Increased, Migration (Endothelial Cells) | Increased, Migration (Endothelial Cells) | |

| KE | 1196 | Increased, Invasion | Increased, Invasion | |

| KE | 1376 | Increase, angiogenesis | Increase, angiogenesis | |

| KE | 1971 | Increased, tumor growth | tumor growth | |

| AO | 1982 | metastatic breast cancer | Metastasis, Breast Cancer |

Key Event Relationships

| Upstream Event | Relationship Type | Downstream Event | Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activation, AhR | adjacent | Increase, Inflammation | High | |

| Activation, AhR | adjacent | Apoptosis | High | |

| Activation, AhR | adjacent | Increased, Motility | High | |

| Activation, AhR | adjacent | Increased, Migration (Endothelial Cells) | Moderate | |

| Activation, AhR | adjacent | Increased, Invasion | High | |

| Increase, Inflammation | adjacent | Increased, Invasion | High | |

| Increase, Inflammation | adjacent | Increase, angiogenesis | High | |

| Increased, Motility | adjacent | Increased, Invasion | High | |

| Increased, Migration (Endothelial Cells) | adjacent | Increase, angiogenesis | High | |

| Apoptosis | adjacent | Increased, tumor growth | High | |

| Increase, angiogenesis | adjacent | metastatic breast cancer | High | High |

| Increased, Invasion | adjacent | metastatic breast cancer | High | High |

| Increased, tumor growth | adjacent | metastatic breast cancer | High | High |

Stressors

| Name | Evidence |

|---|---|

| 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) |

Overall Assessment of the AOP

The biological plausibility of KERs is defined by the OECD as the « understanding of the fundamental biological processes involved and whether they are consistent with the causal relationship being proposed in the AOP ». The biological plausibility is strong due to the presence of overwhelming evidence present in different studies. A minor setback would be the difficulty to dismiss alternative mechanisms caused by the ligands used for AhR activation. This is detailed in the discussion.

The essentiality of KEs refers to « experimental data for whether or not downstream KEs or the AO are prevented or modified if an upstream event is blocked ». The essentiality of KEs is strong: most works use suppression or inhibition of the AhR (knock out, antagonists and/or silencing) with results coherent with our findings.

Finally, the empirical support of KERs, is often « based on toxicological data derived by one or more reference chemicals where dose–response and temporal concordance for the KE pair can be assessed ». The overall assessment of the empirical support of our KERs is also strong. There is evidence in human cell lines and mice showing a dose–response and temporal concordance for severity of our KE and the presence of metastasis.

We propose a simple and robust AOP associating activation of the AhR and breast cancer related death through migration, invasion, inflammation, and neo-angiogenesis.

One of the main limitations of our AOP is the existence of these diverse ligands and pathways, complexifying the definition of ‘AhR activation’ (6,54). Using PubTator, we found that TCDD was by far the most used chemical followed by I3C, alpha-naphthoflavone, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and hexachlorobenzene, all ligands of the AhR. These ligands can activate different pathways after AhR binding and we therefore assumed that these compounds were AhR agonists. It can be difficult to dismiss alternative mechanisms caused by the ligands used for AhR activation. However, the AhR is the only characterized target of TCDD for example, and studies which use several ligands including TCDD, display similar results using the other modulators. Moreover, the concordance of studies using various ligands and the coherence with the AhR inhibition are in favor of the robustness of the proposed AOP. Indeed, to obtain the most accurate AOP possible, the KEs selected had to be present, no matter the ligand used by the study.

Another minor setback of using the AhR, is that the dose response concordance is a non-monotonous curve for several ligands (122,123). Therefore, the tailored Bradford-Hill criteria could sometimes not be fulfilled.

Moreover, the originality of our work lies in the use of artificial intelligence too such as AOP-helpfinder, which enables a thoroughly search of existing knowledge in the PubMed database and PubTator (19–21). Therefore, our literature review was complete and evidence in favor of our proposed AOP was overwhelming. We plan to validate our proposed AOP in a quantitative in vitro work using Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA).

Domain of Applicability

Life Stage Applicability| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Adult | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Female | High |

| Male | Low |

The biological applicability domain of the putative AOP concerned mainly females of menstrual of post-menopausal age. Indeed, existing cell lines were derived from women of menstrual of post-menopausal age and in vivo, studies were performed on mice of reproductive age. Only one study used the zebra fish larvae (Narasimhan et al., 2018 May 7). However, it could be extrapolated to men. Indeed, breast cancers in men present similar tumor characteristics and no work has found diverging functions of the AhR between men and women. Moreover, no difference in AhR expression has been characterized between men and women. Furthermore, our AOP concerns ER-positive and triple negative cells lines.

Studies were carried out in humans, mice, and zebrafish (xenotransplant studies, no mammary gland) (i.e. PubTator results) and it can be hypothesized that this AOP is conserved across mammals. Indeed, the AhR is a very conserved and ancient protein (Hahn, 2002 Sep 20). However, since the sensitivity to adverse events are variable among taxa, we can only postulate this AOP in human and mice (Korkalainen et al., 2001 Aug 3, Cohen-Barnhouse et al., 2011 Jan, Doering et al., 2013 Mar).

The AhR is a fascinating yet complex receptor since its activation is ligand and cell dependent. To avoid more bias, we decided to limit our AOP to breast cancer. First, this cancer is the most frequent female malignancy, which makes it a major public health concern. Second, this illness is hormonal-dependent and therefore the impact of the environment, through the AhR, can be strongly suggested. However, we have reasons to believe this AOP could be extrapolated to other cancers which share common regulatory pathways (Larigot et al., 2022). The AhR is overexpressed not only in breast cancer but also in lung, liver, stomach, head & neck, cervix, and ovarian cancer (Stanford et al., 2016, DiNatale et al., 2010 Aug 6, Liu et al., 2013 Aug, Stanford et al., 2016 Aug). Moreover, in these cancers, the level of expression is correlated to the stage of the disease (Zudaire et al., 2008, Koliopanos et al., 2002 Sep 5, Chang et al., 2007 Jan 1). Additionally, Moenniks et al. found that mice with constitutively active AhR had more liver tumors than wild type mice (55% versus 6%) (Moennikes et al., 2004 Jul 15). In vitro evidence suggests that the AhR activation could promote a more aggressive phenotype to renal, lung, head and neck, and urothelial cancer through an increase in invasion, migration, and resistance to apoptosis which constitute representative key events of our AOP (Zudaire et al., 2008, Stanford et al., 2016 Aug, Ishida et al., 2015 Jul 15, Ishida et al., 2010 Feb, Diry et al., 2006 Sep 7, John et al., 2014 Oct). Besides, an AOP associating AhR activation and lung cancer initiation is currently under development (AOP, 2021) (https://aopwiki.org/aops/417, accessed May 2022).

Likewise, our AOP covers only breast cancer progression and not initiation. The mechanisms of breast cancer initiation are different from the metastatic pathway, but the AhR could also be involved in breast cancer initiation. In vitro, it was noted that human mammary benign cells with a high level of AhR had an increase in cell proliferation, and migration, and potentially display EMT-like features (Brooks and Eltom, 2011 Jun). In vivo, mice fed with 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA, an AhR activator and a potent mutagen) had an increased risk of mammary tumors, with higher AhR expression (Currier et al., 2005). Strangely in regard of the deadly outcomes associated with aggressive breast tumors, the number of studies focusing on this specific aspect of mammary carcinogenesis is limited and therefore, epidemiological data on the effects of the exposome in breast cancer aggressiveness is scarce. Indeed, occupational exposure is difficult to quantify, and patients are usually exposed to a mixture of pollutants and not a single pollutant in a chronic way. A memory bias cannot be excluded since the half-life of TCDD, for instance, is 7–11 years (Pirkle et al., 1989). Industrial accidents, such as the Seveso incident, studied the increase in breast cancer incidence but did not record breast cancer aggressiveness since it is more complex to quantify. At an early stage, breast cancer has a favorable prognosis whereas the therapeutic challenge lies in the treatment of breast cancer metastases. Therefore, even though epidemiologic and cell evidence suggests that exposure to pollutants and Ahr activation could promote breast cancer initiation, we chose to study breast cancer progression, the most complex situation (Pesatori et al., 2009 Sep, Warner et al., 2002 Jul).

Essentiality of the Key Events

| KEY EVENT | LEVEL OF ESSENTIALITY | EVIDENCE | ||

| KE 1262 : decreased apoptosis | Strong |

A decrease in apoptosis is an essentiel element in promoting tumor growth (Hannahan , Fulda). Indeed, in case of a decrease in cell death, the tumor will continue to grow. First, A decrase in apoptosis causes uncontrolled Cell Proliferation. Healthy tissues maintain homeostasis through a balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis. When apoptosis is compromised, cells that should undergo programmed cell death survive and continue dividing. This leads to an unchecked increase in cell number, forming the initial tumor mass. [Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011]. Second, cancer cells sustain proliferative signaling. Many cancers harbor mutations that activate pro-proliferative signaling pathways like Ras or PI3K/Akt. These pathways normally promote cell growth and division. However, mutational dysregulation allows them to continue signaling proliferation even when apoptosis should occur or growth signals are absent. Additionally, reduced apoptosis prevents the activation of pro-apoptotic pathways that normally act as brakes on cell division. [Luo & Heng, 2003] Also, healthy cells respond to cues like density-dependent inhibition and nutrient limitations by activating apoptosis. When apoptosis is compromised, cells can evade these growth-inhibitory signals and continue dividing even when resources are limited or cell density is high. This allows the tumor to expand beyond its boundaries and invade surrounding tissues. [Fulda & Debatin, 2007]. A decrease in apoptosis is therefore essential to maintain tumor growth. However, cell proliferation is also an essentiel element in promoting tumor growth. Yet, due to the presence of diverging evidence on the activation of the AhR and cell proliferation, we chose not to include these in our AOP. Indeed, on one hand, activation of the AhR through ligands such as NK150460, ANI-7, emodine or derivates of revesterol decrease cell proliferation in ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer cell lines. TCDD has been found to promote cell cycle arrest through phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein which binds to E2F. In ER-positive cell lines, beta-naphthoflavone mediated cell cycle arrest through an upregulation of P21. On the other hand, AhR activation could promote cell proliferation. Pearce et al. found that MCDF (6-methyl-1,3,8-trichlorodibenzofuran), an AhR agonist could stimulate cell proliferation with a dose-response concordance. Likewise, I3C, HCB, CPF and licorice could also promote cell proliferation. However, it seems that this cell proliferation is ER-dependent. Indeed, these ligands induced cell proliferation only in ER-positive cells lines with an effect dependent on the level of estrogen present in the medium. Whether this increase in ER-dependent cell proliferation can be independent of the AhR remains unclear. This increase in proliferation could also be mediated by the association of the RelA subunit of NF-kappaB with the AhR resulting in the activation of c-myc gene transcription in breast cancer cells. This would explain why Rodriguez et al. found that proliferation was modulated by the CYP1A1, independently of an exogenous ligand activation of the AhR. These complex effects, highly dependent on the context (cell types, medium content, type of ligand…) were therefore not included in our AOP despite the strong evidence. |

||

| KE 1971 : tumor growth | STRONG | An increase in tumor size is associated with breast cancer metastasis and is essential to the progression of the illness (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011 Mar 4). Indeed, clinical evidence suggests that tumor size is directly correlated to the presence of metastasis (Liu Y, He M, Zuo WJ, Hao S, Wang ZH, Shao ZM. Tumor Size Still Impacts Prognosis in Breast Cancer With Extensive Nodal Involvement. Front Oncol and Narod SA. Tumour size predicts long-term survival among women with lymph node-positive breast cancer. Curr Oncol.) Likewise, studies have shown that larger tumor size in colorectal cancer is associated with increased risk of metastasis and poorer overall survival. [Benson et al., 2008] | ||

|

KE 1241 Increased cell motility |

MODERATE | The relation between cell migration and organ invasion is essntial. Organ invasion can be promonted by cell migration, motility and inflammation. Therefore the essentilality of cell motility was classified as moderate since other factors can promote organ invasion. For instance, melanoma cells are known for their high migratory potential, allowing them to invade the surrounding dermis and potentially metastasize to distant organs like the brain and lungs. [Clark et al., 2009] Likewise, breast cancer cells can migrate through the basement membrane and invade surrounding breast tissue, potentially reaching lymph nodes or blood vessels for further dissemination. [Friedl & Weigelin, 2008] | ||

|

KE 1196: organ invasion |

STRONG | Organ invasion is an essential step in promoting breast cancer agressivness and metastasis. Without invasion of the basal membrane, the cancer remains located in an in situ state and does not induce metastasis. Pancreatic cancer cells are notorious for their invasive nature. They can invade surrounding tissues like the pancreas, blood vessels, and nerves, increasing the risk of metastasis to the liver, lungs, and bones. [Olive et al., 2009] Colorectal cancer cells can invade the bowel wall and potentially reach surrounding blood vessels, allowing them to travel to the liver, lungs, and other distant sites. [Fearon & Vogelstein, 1990] | ||

| KE 149 Increased inflammation | MODERATE |

Organ invasion can be promonted by cell migration, motility and inflammation. Therefore the essentilality of cell motility was classified as moderate since other factors can promote organ invasion. In angiogenesis, however, increased inflammation is a key factor. Indeed, inflammation, through the secretion of growth factor promotes the creation of blood vessels (VEGF, IL6, COX). |

||

| KE 1190 Increased endothelial migration | STRONG | Endothelial cell migration is an essential key event in promoting angiogenesis. Extensive data exists on the essentialitty of this step (Franziska van Zijl, Georg Krupitza, Wolfgang Mikulits, Initial steps of metastasis: Cell invasion and endothelial transmigration, Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research, Volume 728, Issues 1–2, 2011, Pages 23-34, ISSN 1383-5742, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.05.002.) | ||

| KE 1213: angiogenesis | STRONG | Without the creation of new vessels in order to receive nutrients and energy, the cancer cell cannot survive and create metastatis. It is an essential key event and considered as one of the hallmarks of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011 Mar 4). |

Weight of Evidence Summary

KER 2569 Activation of the AhR leads to decreased apoptosis

Several studies have found that the activation of the AhR by stressors such as TCDD, can promote a decrease in apoptosis (KER2569), which is a deleterious event with regards to cancer (Al-Dhfyan et al., 2017 Jan 19, Bekki et al., 2015). Additionally, an increase in cell death was found when blocking the AhR pathway using AhR silencing (RNA interference or knock-out), knockout cell lines or antagonists (CH223191 or alpha-naphthoflavone) (Goode et al., 2013 Dec 15, Al-Dhfyan et al., 2017 Jan 19, Bekki et al., 2015, Regan Anderson et al., 2018). The most frequently used assay to evaluate apoptosis was cytometry with the use of Annexin V: this was performed with ER-positive cells lines (MCF-7, T-47D), triple negative cell lines (MDA-MB-231, HS 578), cells over-expressing the Her2 (SK-BR-3) and cells lines derived from cancer samples from patients (Goode et al., 2013 Dec 15, Al-Dhfyan et al., 2017 Jan 19, Bekki et al., 2015, Regan Anderson et al., 2018, Fujisawa et al., 2011).

The concordance of the evidence was classified as “moderate” since the aim of most studies was to evaluate the capacity to survive in an apoptosis-promoting environment (i.e., chemotherapeutic drugs). Indeed, they assessed the resistance to chemotherapy agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel and found that the concomitant inactivation of the AhR pathway could decrease the resistance to these chemotherapy agents through an increase in cell death when compared to cells with a functional (or expressed at sufficient levels) AhR (Goode et al., 2013 Dec 15, Al-Dhfyan et al., 2017 Jan 19, Bekki et al., 2015, Regan Anderson et al., 2018, Fujisawa et al., 2011). Since the environment was modified by the presence of chemotherapy, the hypothesis of an alternative pathway cannot be completely discarded. It must be noticed that the exact biological mechanisms linking the activation of the AhR to the decrease in apoptosis remains unclear. Indeed, Anderson et al. suggested that the AhR interacts with the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and the hypoxia inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) (Regan Anderson et al., 2018). The presence of the GR is associated with a poor prognosis, notably in triple negative breast cancer (Pan et al., 2011, Moran et al., 2000 Feb 15). Indeed, this receptor is involved in survival and resistance to chemotherapy through up-regulation of c-myc, Bcl2 and Kruppel-like factor 5 (Pan et al., 2011, Wu et al., 2004, Li et al., 2017). Both GR and HIF 2α could be up regulated by the AhR. They then activate Brk (also known as PTK6), a ligand of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor), involved in the inhibition of apoptosis (Regan Anderson et al., 2018, Li et al., 2012). Another possible mechanism suggested by Bekki et al. is that the decrease in apoptosis was caused by the induction of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) and the NF-κB subunit RelB (Bekki et al., 2015). They both prevent apoptosis through induction of Bcl2, an anti-apoptotic factor (Tsujii and DuBois, 1995, Vogel et al., 2007, Thomas et al., 2020, Baud and Jacque, 2008 Dec, Demicco et al., 2005 Nov, Wang et al., 2007 Apr, Liu et al., 2001 May 25).

KER 2577: Decreased apoptosis promotes tumor growth

For KER 2577, in vivo, Goode et al. showed that the knockout of the AhR in mice reduced tumor growth through an increase of cell apoptosis (Goode et al., 2013 Dec 15).

The relationship between decreased apoptosis and increase in tumor growth (KER 2577) is not detailed here due to extensive evidence in the scientific literature (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011 Mar 4).

KER 2570: Activation of the AhR leads to an increased cell motility

The activation of the AhR can modulate cell motility in different types of breast cancers such as: ER-positive cells lines (MCF-7, T-47D, ZR-75–1), triple negative (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, HS-578-T, SUM149), and cells overexpressing the Her2 (SK-BR-3) (Goode et al., 2013 Dec 15, Regan Anderson et al., 2018, Parks et al., 2014 Nov, Pontillo et al., 2011 Apr, Qin et al., 2011 Oct 20, Nguyen et al., 2016 Nov 15, Novikov et al., 2016 Nov, Miret et al., 2016 Jul, Shan et al., 2020 Nov, Dwyer et al., 2021 Feb, Narasimhan et al., 2018 May 7, Hsieh et al., 2012 Feb). Activation of the AhR with TCDD, butyl-benzyl phthalate, di-n-butyl phthalate, hexachlorobenzene, and benzo[a]pyrene can promote cell migration in different assays (Parks et al., 2014 Nov, Pontillo et al., 2011 Apr, Qin et al., 2011 Oct 20, Novikov et al., 2016 Nov, Miret et al., 2016 Jul, Shan et al., 2020 Nov, Narasimhan et al., 2018 May 7, Hsieh et al., 2012 Feb). On the other hand, the use of AhR antagonists, AhR silencing or AhR knockout reversed this effect (Goode et al., 2013 Dec 15, Regan Anderson et al., 2018, Parks et al., 2014 Nov, Pontillo et al., 2011 Apr, Qin et al., 2011 Oct 20, Novikov et al., 2016 Nov, Shan et al., 2020 Nov, Narasimhan et al., 2018 May 7, Hsieh et al., 2012 Feb). The most frequently used assays for evaluating cell migration were the scratch wound assay and the transwell chamber assay. Only three works evaluated the dose–response concordance of AhR activation with stressors and cell migration (Pontillo et al., 2011 Apr, Miret et al., 2016 Jul, Shan et al., 2020 Nov). The evidence was therefore classified as “moderate”.

KER 2572: Activation of the AhR leads to an increased invasion

Due to the extensive robust and concordant literature of the link between activation of the AhR-increased cell motility-increased invasion-breast cancer progression, the confidence in these key events was rated as high. However, due to the use of ligands to activate the AhR, it cannot be completely ruled out that alternative pathways (independent of the AhR) can also contribute to these features. For instance, 2 main pathways seem to explain this increase in migration and invasion: the c-Src/HER1/STAT5b, and ERK1/2 pathways. Yet, these pathways seem only to explain the relation between the AhR activation and cell migration / invasion, when the ligand used is hexachlorobenzene, an organochlorinated pesticide (Pontillo et al., 2011 Apr, Miret et al., 2016 Jul, Pontillo et al., 2013 May 1). Even though alternative mechanisms may present themselves, all studies blocked the AhR pathway and found a decrease in cell migration/invasion. The evidence for alternative mechanisms was therefore classified as “moderate” and the biological plausibility of KER was also classified as “moderate”.

KER 1306: Increased cell motility promotes organ invasion

The relation between cell migration and organ invasion has already been shown (KER-1306, https://aopwiki.org/relationships/1306). Since the 2 are closely linked, most articles studied both cell migration (chemo-tactic) and the capacity to invade the extra-cellular matrix. Cell invasion is indeed defined as the capacity of a cell to migrate and degrade/invade the extracellular matrix. In vitro, this process was evaluated mostly using transwell chamber with Matrigel® and the presence of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP). This effect was found in ER-positive cells, triple negative cell lines and cells overexpressing the Her2.

KER 2572: Activation of the AhR leads to an increased invasion

The activation of the AhR through the use of different ligands (benzophenone, butyl benzyl phthalate, di-n-butyl phthalate, hexachlorobenzene, chlorpyrifos, TCDD) or the blockage of the AhR (silencing, KO or antagonism) increased or decreased cell invasion, respectively (Parks et al., 2014 Nov, Qin et al., 2011 Oct 20, Nguyen et al., 2016 Nov 15, Miret et al., 2016 Jul, Shan et al., 2020 Nov, Narasimhan et al., 2018 May 7, Hsieh et al., 2012 Feb, Pontillo et al., 2013 May 1, Miller et al., 2005, Belguise et al., 2007 Dec 15, Yamashita et al., 2018 May 1, Miret et al., 2020 May). The dose–response concordance for cell invasion was demonstrated using increasing doses of hexachlorobenzene, benzo[a]pyrene, chlorpyrifos and TCDD (Miret et al., 2016 Jul, Shan et al., 2020 Nov, Pontillo et al., 2013 May 1, Miller et al., 2005, Miret et al., 2020 May). To further explore cell invasion, Nguyen et al. created a model of a lymphatic barrier using a three-dimensional lymph endothelial cell as a monolayer co-cultured with spheroids of MDA-MB231 cells (Nguyen et al., 2016 Nov 15). They found that silencing or antagonizing the AhR (DIM) or activating the AhR (FICZ) respectively decreased or increased invasion of the lymphatic barrier.

On an organ level, in vivo, an increase in metastasis has been found in mice and zebrafish after the activation of the AhR with different ligands (butyl benzyl phthalate, di-n-butyl phthalate, hexachlorobenzene, TCDD) (Goode et al., 2014, Shan et al., 2020 Nov, Narasimhan et al., 2018 May 7, Hsieh et al., 2012 Feb, Pontillo et al., 2013 May 1). In the zebrafish model, Narasimham et al. treated the animals either with triple negative MDA-MB-231 cells only (untreated) or with MDA-MB-231 cells treated with an AhR inhibitor (CB7993113 or CH22319) (Narasimhan et al., 2018 May 7). Untreated fish had significantly more metastasis (OR = 9, IC95%=3–35). Similar results were found using mice models (Goode et al., 2014, Shan et al., 2020 Nov, Narasimhan et al., 2018 May 7, Hsieh et al., 2012 Feb, Pontillo et al., 2013 May 1).

KER 2568: Activation of the AhR leads to an increased inflammation

In triple negative breast cell lines (MDA-MB436, MDA-MB-231) and ER-positive cell lines, it has been shown that the activation of the AhR can lead to an increase in inflammation. (Bekki et al., 2015, Miller et al., 2005, Yamashita et al., 2018 May 1, Degner et al., 2009 Jan, Vogel et al., 2011 Aug 1, Kolasa et al., 2013 Apr 25, Vacher et al., 2018, Malik et al., 2019 Oct). The stressors mainly used to activate the AhR were TCDD followed by benzo[a]pyrene and 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo [4, 5-b] pyridine (PhiP). After AhR inhibition (KO or antagonists), a decrease in inflammation biomarkers was found (Miller et al., 2005, Yamashita et al., 2018 May 1, Degner et al., 2009 Jan, Vogel et al., 2011 Aug 1, Kolasa et al., 2013 Apr 25). Assays evaluating cell inflammation were quantitative dosages of IL-6, IL-8 and Cox2 activity/expression. Cox-2 and IL-8 were amongst the top “gene concepts” retrieved by the PubTator Central tool, likewise, “inflammation” was frequently found as a disease concept. The most consensual pathway linking the AhR activation to cell inflammation was the NF-kB pathway (Vogel et al., 2011 Aug 1, Kolasa et al., 2013 Apr 25). Only half of the studies found a dose–response relationship (Miller et al., 2005, Kolasa et al., 2013 Apr 25, Malik et al., 2019 Oct). No studies were carried out in vivo for breast cancer and therefore the concordance and evidence were classified as “moderate”.

AOP 21 also found the association between AhR activation and inflammation via COX 2 (Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation leading to early life stage mortality, via increased COX-2) with a weight of evidence classified as “high”. Indeed, the AhR/ARNT heterodimer links to the dioxin responsive elements which in turn up-regulates COX-2 (66,67].

KER 2573: Inflammation promotes organ invasion

In the specific setting of AhR activation, only 2 studies showed the continuum between AhR activation – increased inflammation – increased invasion (Miller et al., 2005, Yamashita et al., 2018 May 1). However, in general, there is extensive knowledge on the relationship between cell inflammation and organ invasion. First, COX-2 is expressed at higher levels in triple negative invasive breast cancers than in less aggressive ER-positive cancers (Gilhooly and Rose, 1999 Aug, Liu and Rose, 1996 Nov 15). COX-2 catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandin H2, a pro-inflammatory factor, and is therefore considered as a prognosis factor in breast cancer (Ristimäki et al., 2002 Feb 1, Parrett et al., 1997 Mar). Transfection with COX-2 triple negative MDA-MB-435 cells increased cell migration 2-fold compared to control cells in a transwell-Matrigel® assay. Antagonism of COX-2 through an inhibitor (NS-398) reversed this action in a dose-dependent way (Singh et al., 2005 May). Second, in vivo, the use of anti-inflammatory treatments such as celecoxib (COX-2 inhibitor) can reduce tumor growth and spread (Harris et al., 2000 Apr 15). Finally, epidemiologic evidence suggests that inflammatory breast cancers have the worse prognosis. Indeed, the median overall survival of patients with inflammatory breast cancer compared with those with non-inflammatory breast cancer tumors is 4.75 years versus 13.40 years for stage III disease and 2.27 years versus 3.40 years for stage IV disease (Schlichting et al., 2012 Aug, Fouad et al., 2017 Apr).

The mechanism of action of COX-2 are consensual. COX-2 promotes cell invasion through upregulation of MMPs (notably 2 and 9) (Takahashi et al., 1999 Oct 22, Sivula et al., 2005 Feb, Larkins et al., 2006 Jul). Moreover, COX-2 could also activate the urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) which degrades the basal membrane of epithelia (Singh et al., 2005 May, Takahashi et al., 1999 Oct 22, Larkins et al., 2006 Jul, Guyton et al., 2000 Mar).

The relationship between inflammation and invasion is well document therefore the evidence was classified as “strong”.

KER 2574: Inflammation promotes angiogenesis

Likewise, two studies evaluated the specific continuum AhR activation – increased inflammation – increased angiogenesis (Pontillo et al., 2015 Nov 19, Zárate et al., 2020 Aug). As previously mentioned, the AhR activation increases inflammation, notably through an increase in COX 2 (Bekki et al., 2015, Miller et al., 2005, Degner et al., 2009 Jan, Pontillo et al., 2015 Nov 19, Zárate et al., 2020 Aug).

COX-2 can promote angiogenesis through an increase in VEGF (Vascular endothelial growth factor) (Harris et al., 2014 Oct 10, Kirkpatrick et al., 2002). In a pathologic study characterizing 46 breast cancer specimen using immunochemistry, it was found that the density of microvessels was significantly higher in patients with COX-2 expression than in those without expression (p = 0.03) (Costa et al., 2002 Jun). The relationship between COX-2 and angiogenesis has also been shown in gastric and colorectal cancer (Tsujii et al., 1998 May 29, Uefuji et al., 2000 Jan). Indeed, colon carcinoma cells overexpressing COX-2 produce proangiogenic factors (VEGF, bFGF, TBF-β, PDGF, and endothelin-1), and stimulate endothelial migration and the formation of tube vessels. These effects were reversed by an inhibitor (NS-398). In vivo, Diclofenac, a COX-2 inhibitor, decreased angiogenesis in mice presenting a colorectal cancer (Seed et al., 1997 May 1). Likewise, in a murine model of breast cancer, celecoxib (a selective COX-2 inhibitor) reduced metastasis and tumor burden through a decrease of micro vessel density and VEGF (Yoshinaka et al., 2006 Dec, Zhang et al., 2004 Sep). In clinical studies, patients with inflammatory breast cancers have increased levels of genes involved in angiogenesis such as VEGF (Van der Auwera et al., 2004 Dec 1). Patients with an inflammatory breast cancer benefit the most from anti-angiogenic treatment bevacizumab (Pierga et al., 2012 Apr).

The evidence was classified as “moderate” due to the lack of dose response studies.

KER 1266: Activation of the AhR leads to an increased endothelial migration

The activation of the AhR can lead to an increased endothelial cell migration. This was found when HMEC-1 or EA.hy926 cells were co-cultured with ER-positive MCF-7 cells and triple negative MDA-MB-231 cells (Pontillo et al., 2015 Nov 19, Zárate et al., 2020 Aug). The assay mainly used was the Matrigel® / tube formation assay. Only one study found an increase in endothelial cell proliferation and not migration, therefore it was not kept as a KE (Pontillo et al., 2015 Nov 19). The main pathway explaining this relationship was again related to the activation of COX2 and subsequently to the increase in VEGF. The association between the activation of the AhR and endothelial cell migration was classified as “weak” since only 2 studies explored this feature, and both used hexachlorobenzene as a stressor. However, these works were robust with strong evidence, and both found a reversed association after AhR blockage. No contradicting results were found in the scientific literature.

As opposed to our work, another AOP displayed a link between AhR activation and angiogenesis (AOP 150) and found that activation of the receptor could decrease VEGF production with moderate evidence and quantitative understanding. It must be noted that these AOPs applied only to chicken, zebrafish, and certain rodents whereas our AOP concerns humans. As detailed further, the AhR presents a variability between species which must be considered.

KER 1267: Increased endothelial migration promotes angiogenesis

Pontillo et al. treated mice with increasing doses of hexachlorobenzene and then calculated the vessel density in mammary fat pads (Pontillo et al., 2015 Nov 19). They found that mice treated with hexachlorobenzene had a higher vessel density with a dose–response concordance. Treatment by AhR antagonists completely reversed this association (Pontillo et al., 2015 Nov 19, Zárate et al., 2020 Aug). The relationship between endothelial migration and angiogenesis was not detailed here since there is existing extensive knowledge (Lamalice et al., 2007 Mar 30, Norton and Popel, 2016 Nov 14, Ausprunk and Folkman, 1977 Jul 1). The KER 12 was considered as “strong”.

KER 3137, 3138 and 3137: Increased tumor growth, increased invasion, and increased angiogenesis lead to breast cancer metastasis

Due to extensive data in the scientific literature and the empirical evidence in favor of these KERs, these KERs were not detailed here.

References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

2. Henley SJ, Ward EM, Scott S, Ma J, Anderson RN, Firth AU, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 2020 May 15;126(10):2225–49.

3. Koual M, Tomkiewicz C, Cano-Sancho G, Antignac JP, Bats AS, Coumoul X. Environmental chemicals, breast cancer progression and drug resistance. Environ Health Glob Access Sci Source. 2020 Nov 17;19(1):117.

4. Koual M, Cano-Sancho G, Bats AS, Tomkiewicz C, Kaddouch-Amar Y, Douay-Hauser N, et al. Associations between persistent organic pollutants and risk of breast cancer metastasis. Environ Int. 2019;132:105028.

5. Koual M, Tomkiewicz C, Guerrera IC, Sherr D, Barouki R, Coumoul X. Aggressiveness and Metastatic Potential of Breast Cancer Cells Co-Cultured with Preadipocytes and Exposed to an Environmental Pollutant Dioxin: An in Vitro and in Vivo Zebrafish Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2021 Mar;129(3):37002.

6. Larigot L, Benoit L, Koual M, Tomkiewicz C, Barouki R, Coumoul X. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and Its Diverse Ligands and Functions: An Exposome Receptor. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021 Sep 9;

7. Zudaire E, Cuesta N, Murty V, Woodson K, Adams L, Gonzalez N, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor is a putative tumor suppressor gene in multiple human cancers. J Clin Invest. 2008 Feb;118(2):640–50.

8. Kim DW, Gazourian L, Quadri SA, Romieu-Mourez R, Sherr DH, Sonenshein GE. The RelA NF-kappaB subunit and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) cooperate to transactivate the c-myc promoter in mammary cells. Oncogene. 2000 Nov 16;19(48):5498–506.

9. Li ZD, Wang K, Yang XW, Zhuang ZG, Wang JJ, Tong XW. Expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in relation to p53 status and clinicopathological parameters in breast cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(11):7931–7.

10. Zhao S, Ohara S, Kanno Y, Midorikawa Y, Nakayama M, Makimura M, et al. HER2 overexpression-mediated inflammatory signaling enhances mammosphere formation through up-regulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor transcription. Cancer Lett. 2013 Mar 1;330(1):41–8.

11. Goode GD, Ballard BR, Manning HC, Freeman ML, Kang Y, Eltom SE. Knockdown of aberrantly upregulated aryl hydrocarbon receptor reduces tumor growth and metastasis of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell line. Int J Cancer. 2013 Dec 15;133(12):2769–80.

12. Kanno Y, Takane Y, Izawa T, Nakahama T, Inouye Y. The inhibitory effect of aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor (AhRR) on the growth of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006 Jun;29(6):1254–7.

13. Stanford EA, Wang Z, Novikov O, Mulas F, Landesman-Bollag E, Monti S, et al. The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the development of cells with the molecular and functional characteristics of cancer stem-like cells. BMC Biol. 2016 Mar 16;14:20.

14. Goode G, Pratap S, Eltom SE. Depletion of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells altered the expression of genes in key regulatory pathways of cancer. PloS One. 2014;9(6):e100103.

15. Safe S, Wormke M, Samudio I. Mechanisms of inhibitory aryl hydrocarbon receptor-estrogen receptor crosstalk in human breast cancer cells. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2000 Jul;5(3):295–306.

16. Carvaillo JC, Barouki R, Coumoul X, Audouze K. Linking Bisphenol S to Adverse Outcome Pathways Using a Combined Text Mining and Systems Biology Approach. Environ Health Perspect. 2019 Apr;127(4):47005.

17. Zgheib E, Kim MJ, Jornod F, Bernal K, Tomkiewicz C, Bortoli S, et al. Identification of non-validated endocrine disrupting chemical characterization methods by screening of the literature using artificial intelligence and by database exploration. Environ Int. 2021 Sep;154:106574.

18. Rugard M, Coumoul X, Carvaillo JC, Barouki R, Audouze K. Deciphering Adverse Outcome Pathway Network Linked to Bisphenol F Using Text Mining and Systems Toxicology Approaches. Toxicol Sci Off J Soc Toxicol. 2020 Jan 1;173(1):32–40.

19. Jornod F, Rugard M, Tamisier L, Coumoul X, Andersen HR, Barouki R, et al. AOP4EUpest: mapping of pesticides in adverse outcome pathways using a text mining tool. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2020 Aug 1;36(15):4379–81.

20. Jornod F, Jaylet T, Blaha L, Sarigiannis D, Tamisier L, Audouze K. AOP-helpFinder webserver: a tool for comprehensive analysis of the literature to support adverse outcome pathways development. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2021 Oct 30;btab750.

21. Wei CH, Kao HY, Lu Z. PubTator: a web-based text mining tool for assisting biocuration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 Jul;41(Web Server issue):W518-522.

22. Wei CH, Allot A, Leaman R, Lu Z. PubTator central: automated concept annotation for biomedical full text articles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019 Jul 2;47(W1):W587–93.

23. OECD. Users’ Handbook supplement to the Guidance Document for developing and assessing Adverse Outcome Pathways. 2018 Feb 14 [cited 2021 Sep 14]; Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/users-handbook-supplement-to-the-guidance-document-for-developing-and-assessing-adverse-outcome-pathways_5jlv1m9d1g32-en

24. Hill AB. The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965 May;58(5):295–300.

25. Vinken M, Landesmann B, Goumenou M, Vinken S, Shah I, Jaeschke H, et al. Development of an adverse outcome pathway from drug-mediated bile salt export pump inhibition to cholestatic liver injury. Toxicol Sci Off J Soc Toxicol. 2013 Nov;136(1):97–106.

26. Becker RA, Ankley GT, Edwards SW, Kennedy SW, Linkov I, Meek B, et al. Increasing Scientific Confidence in Adverse Outcome Pathways: Application of Tailored Bradford-Hill Considerations for Evaluating Weight of Evidence. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015 Aug 1;72(3):514–37.

27. Al-Dhfyan A, Alhoshani A, Korashy HM. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor/cytochrome P450 1A1 pathway mediates breast cancer stem cells expansion through PTEN inhibition and β-Catenin and Akt activation. Mol Cancer. 2017 Jan 19;16(1):14.

28. Bekki K, Vogel H, Li W, Ito T, Sweeney C, Haarmann-Stemmann T, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) mediates resistance to apoptosis induced in breast cancer cells. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2015 May;120:5–13.

29. Regan Anderson TM, Ma S, Perez Kerkvliet C, Peng Y, Helle TM, Krutilina RI, et al. Taxol Induces Brk-dependent Prosurvival Phenotypes in TNBC Cells through an AhR/GR/HIF-driven Signaling Axis. Mol Cancer Res MCR. 2018 Nov;16(11):1761–72.

30. Fujisawa Y, Li W, Wu D, Wong P, Vogel C, Dong B, et al. Ligand-independent activation of the arylhydrocarbon receptor by ETK (Bmx) tyrosine kinase helps MCF10AT1 breast cancer cells to survive in an apoptosis-inducing environment. Biol Chem. 2011 Oct;392(10):897–908.

31. Pan D, Kocherginsky M, Conzen SD. Activation of the glucocorticoid receptor is associated with poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011 Oct 15;71(20):6360–70.

32. Moran TJ, Gray S, Mikosz CA, Conzen SD. The glucocorticoid receptor mediates a survival signal in human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2000 Feb 15;60(4):867–72.

33. Wu W, Chaudhuri S, Brickley DR, Pang D, Karrison T, Conzen SD. Microarray analysis reveals glucocorticoid-regulated survival genes that are associated with inhibition of apoptosis in breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004 Mar 1;64(5):1757–64.

34. Li Z, Dong J, Zou T, Du C, Li S, Chen C, et al. Dexamethasone induces docetaxel and cisplatin resistance partially through up-regulating Krüppel-like factor 5 in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017 Feb 14;8(7):11555–65.

35. Li X, Lu Y, Liang K, Hsu JM, Albarracin C, Mills GB, et al. Brk/PTK6 sustains activated EGFR signaling through inhibiting EGFR degradation and transactivating EGFR. Oncogene. 2012 Oct 4;31(40):4372–83.

36. Tsujii M, DuBois RN. Alterations in cellular adhesion and apoptosis in epithelial cells overexpressing prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2. Cell. 1995 Nov 3;83(3):493–501.

37. Vogel CFA, Li W, Sciullo E, Newman J, Hammock B, Reader JR, et al. Pathogenesis of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated development of lymphoma is associated with increased cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Am J Pathol. 2007 Nov;171(5):1538–48.

38. Thomas E, Dragojevic S, Price A, Raucher D. Thermally Targeted p50 Peptide Inhibits Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis of Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Macromol Biosci. 2020 Oct;20(10):e2000170.

39. Baud V, Jacque E. [The alternative NF-kB activation pathway and cancer: friend or foe?]. Med Sci MS. 2008 Dec;24(12):1083–8.

40. Demicco EG, Kavanagh KT, Romieu-Mourez R, Wang X, Shin SR, Landesman-Bollag E, et al. RelB/p52 NF-kappaB complexes rescue an early delay in mammary gland development in transgenic mice with targeted superrepressor IkappaB-alpha expression and promote carcinogenesis of the mammary gland. Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Nov;25(22):10136–47.

41. Wang X, Belguise K, Kersual N, Kirsch KH, Mineva ND, Galtier F, et al. Oestrogen signalling inhibits invasive phenotype by repressing RelB and its target BCL2. Nat Cell Biol. 2007 Apr;9(4):470–8.

42. Liu CH, Chang SH, Narko K, Trifan OC, Wu MT, Smith E, et al. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 is sufficient to induce tumorigenesis in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2001 May 25;276(21):18563–9.

43. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011 Mar 4;144(5):646–74.

44. Parks AJ, Pollastri MP, Hahn ME, Stanford EA, Novikov O, Franks DG, et al. In silico identification of an aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonist with biological activity in vitro and in vivo. Mol Pharmacol. 2014 Nov;86(5):593–608.

45. Pontillo CA, García MA, Peña D, Cocca C, Chiappini F, Alvarez L, et al. Activation of c-Src/HER1/STAT5b and HER1/ERK1/2 signaling pathways and cell migration by hexachlorobenzene in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell line. Toxicol Sci Off J Soc Toxicol. 2011 Apr;120(2):284–96.

46. Qin XY, Wei F, Yoshinaga J, Yonemoto J, Tanokura M, Sone H. siRNA-mediated knockdown of aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator 2 affects hypoxia-inducible factor-1 regulatory signaling and metabolism in human breast cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2011 Oct 20;585(20):3310–5.

47. Nguyen CH, Brenner S, Huttary N, Atanasov AG, Dirsch VM, Chatuphonprasert W, et al. AHR/CYP1A1 interplay triggers lymphatic barrier breaching in breast cancer spheroids by inducing 12(S)-HETE synthesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2016 Nov 15;25(22):5006–16.

48. Novikov O, Wang Z, Stanford EA, Parks AJ, Ramirez-Cardenas A, Landesman E, et al. An Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor-Mediated Amplification Loop That Enforces Cell Migration in ER-/PR-/Her2- Human Breast Cancer Cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2016 Nov;90(5):674–88.

49. Miret N, Pontillo C, Ventura C, Carozzo A, Chiappini F, Kleiman de Pisarev D, et al. Hexachlorobenzene modulates the crosstalk between the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and transforming growth factor-β1 signaling, enhancing human breast cancer cell migration and invasion. Toxicology. 2016 Jul 29;366–367:20–31.

50. Shan A, Leng L, Li J, Luo XM, Fan YJ, Yang Q, et al. TCDD-induced antagonism of MEHP-mediated migration and invasion partly involves aryl hydrocarbon receptor in MCF7 breast cancer cells. J Hazard Mater. 2020 Nov 5;398:122869.

51. Dwyer AR, Kerkvliet CP, Krutilina RI, Playa HC, Parke DN, Thomas WA, et al. Breast Tumor Kinase (Brk/PTK6) Mediates Advanced Cancer Phenotypes via SH2-Domain Dependent Activation of RhoA and Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) Signaling. Mol Cancer Res MCR. 2021 Feb;19(2):329–45.

52. Narasimhan S, Stanford Zulick E, Novikov O, Parks AJ, Schlezinger JJ, Wang Z, et al. Towards Resolving the Pro- and Anti-Tumor Effects of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 May 7;19(5):1388.

53. Hsieh TH, Tsai CF, Hsu CY, Kuo PL, Lee JN, Chai CY, et al. Phthalates induce proliferation and invasiveness of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer through the AhR/HDAC6/c-Myc signaling pathway. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. 2012 Feb;26(2):778–87.

54. Pontillo CA, Rojas P, Chiappini F, Sequeira G, Cocca C, Crocci M, et al. Action of hexachlorobenzene on tumor growth and metastasis in different experimental models. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013 May 1;268(3):331–42.

55. Miller ME, Holloway AC, Foster WG. Benzo-[a]-pyrene increases invasion in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells via increased COX-II expression and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) output. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2005;22(2):149–56.

56. Belguise K, Guo S, Yang S, Rogers AE, Seldin DC, Sherr DH, et al. Green tea polyphenols reverse cooperation between c-Rel and CK2 that induces the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, slug, and an invasive phenotype. Cancer Res. 2007 Dec 15;67(24):11742–50.

57. Yamashita N, Saito N, Zhao S, Terai K, Hiruta N, Park Y, et al. Heregulin-induced cell migration is promoted by aryl hydrocarbon receptor in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2018 May 1;366(1):34–40.

58. Miret N, Zappia CD, Altamirano G, Pontillo C, Zárate L, Gómez A, et al. AhR ligands reactivate LINE-1 retrotransposon in triple-negative breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231 and non-tumorigenic mammary epithelial cells NMuMG. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020 May;175:113904.

59. Degner SC, Papoutsis AJ, Selmin O, Romagnolo DF. Targeting of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated activation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression by the indole-3-carbinol metabolite 3,3’-diindolylmethane in breast cancer cells. J Nutr. 2009 Jan;139(1):26–32.

60. Vogel CFA, Li W, Wu D, Miller JK, Sweeney C, Lazennec G, et al. Interaction of aryl hydrocarbon receptor and NF-κB subunit RelB in breast cancer is associated with interleukin-8 overexpression. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011 Aug 1;512(1):78–86.

61. Kolasa E, Houlbert N, Balaguer P, Fardel O. AhR- and NF-κB-dependent induction of interleukin-6 by co-exposure to the environmental contaminant benzanthracene and the cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α in human mammary MCF-7 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2013 Apr 25;203(2):391–400.

62. Vacher S, Castagnet P, Chemlali W, Lallemand F, Meseure D, Pocard M, et al. High AHR expression in breast tumors correlates with expression of genes from several signaling pathways namely inflammation and endogenous tryptophan metabolism. PloS One. 2018;13(1):e0190619.

63. Malik DES, David RM, Gooderham NJ. Interleukin-6 selectively induces drug metabolism to potentiate the genotoxicity of dietary carcinogens in mammary cells. Arch Toxicol. 2019 Oct;93(10):3005–20.

64. Jönsson ME, Kubota A, Timme-Laragy AR, Woodin B, Stegeman JJ. Ahr2-dependence of PCB126 effects on the swim bladder in relation to expression of CYP1 and cox-2 genes in developing zebrafish. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012 Dec 1;265(2):166–74.

65. Degner SC, Kemp MQ, Hockings JK, Romagnolo DF. Cyclooxygenase-2 promoter activation by the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor in breast cancer mcf-7 cells: repressive effects of conjugated linoleic acid. Nutr Cancer. 2007;59(2):248–57.

66. Gilhooly EM, Rose DP. The association between a mutated ras gene and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human breast cancer cell lines. Int J Oncol. 1999 Aug;15(2):267–70.

67. Liu XH, Rose DP. Differential expression and regulation of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in two human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1996 Nov 15;56(22):5125–7.

68. Ristimäki A, Sivula A, Lundin J, Lundin M, Salminen T, Haglund C, et al. Prognostic significance of elevated cyclooxygenase-2 expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002 Feb 1;62(3):632–5.

69. Parrett M, Harris R, Joarder F, Ross M, Clausen K, Robertson F. Cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in human breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 1997 Mar;10(3):503–7.

70. Singh B, Berry JA, Shoher A, Ramakrishnan V, Lucci A. COX-2 overexpression increases motility and invasion of breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2005 May;26(5):1393–9.

71. Harris RE, Alshafie GA, Abou-Issa H, Seibert K. Chemoprevention of breast cancer in rats by celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2000 Apr 15;60(8):2101–3.

72. Schlichting JA, Soliman AS, Schairer C, Schottenfeld D, Merajver SD. Inflammatory and non-inflammatory breast cancer survival by socioeconomic position in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, 1990-2008. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012 Aug;134(3):1257–68.

73. Fouad TM, Barrera AMG, Reuben JM, Lucci A, Woodward WA, Stauder MC, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer: a proposed conceptual shift in the UICC-AJCC TNM staging system. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Apr;18(4):e228–32.

74. Takahashi Y, Kawahara F, Noguchi M, Miwa K, Sato H, Seiki M, et al. Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in human breast cancer cells overexpressing cyclooxygenase-1 or -2. FEBS Lett. 1999 Oct 22;460(1):145–8.

75. Sivula A, Talvensaari-Mattila A, Lundin J, Joensuu H, Haglund C, Ristimäki A, et al. Association of cyclooxygenase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005 Feb;89(3):215–20.

76. Larkins TL, Nowell M, Singh S, Sanford GL. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 decreases breast cancer cell motility, invasion and matrix metalloproteinase expression. BMC Cancer. 2006 Jul 10;6:181.

77. Guyton DP, Evans DM, Sloan-Stakleff KD. Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor (uPAR): A Potential Indicator of Invasion for In Situ Breast Cancer. Breast J. 2000 Mar;6(2):130–6.

78. Pontillo C, Español A, Chiappini F, Miret N, Cocca C, Alvarez L, et al. Hexachlorobenzene promotes angiogenesis in vivo, in a breast cancer model and neovasculogenesis in vitro, in the human microvascular endothelial cell line HMEC-1. Toxicol Lett. 2015 Nov 19;239(1):53–64.

79. Zárate LV, Pontillo CA, Español A, Miret NV, Chiappini F, Cocca C, et al. Angiogenesis signaling in breast cancer models is induced by hexachlorobenzene and chlorpyrifos, pesticide ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2020 Aug 15;401:115093.

80. Harris RE, Casto BC, Harris ZM. Cyclooxygenase-2 and the inflammogenesis of breast cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2014 Oct 10;5(4):677–92.

81. Kirkpatrick K, Ogunkolade W, Elkak A, Bustin S, Jenkins P, Ghilchik M, et al. The mRNA expression of cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in human breast cancer. Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;18(4):237–41.

82. Costa C, Soares R, Reis-Filho JS, Leitão D, Amendoeira I, Schmitt FC. Cyclo-oxygenase 2 expression is associated with angiogenesis and lymph node metastasis in human breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002 Jun;55(6):429–34.

83. Tsujii M, Kawano S, Tsuji S, Sawaoka H, Hori M, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell. 1998 May 29;93(5):705–16.

84. Uefuji K, Ichikura T, Mochizuki H. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is related to prostaglandin biosynthesis and angiogenesis in human gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2000 Jan;6(1):135–8.

85. Seed MP, Brown JR, Freemantle CN, Papworth JL, Colville-Nash PR, Willis D, et al. The inhibition of colon-26 adenocarcinoma development and angiogenesis by topical diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronan. Cancer Res. 1997 May 1;57(9):1625–9.

86. Yoshinaka R, Shibata MA, Morimoto J, Tanigawa N, Otsuki Y. COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib suppresses tumor growth and lung metastasis of a murine mammary cancer. Anticancer Res. 2006 Dec;26(6B):4245–54.

87. Zhang S, Lawson KA, Simmons-Menchaca M, Sun L, Sanders BG, Kline K. Vitamin E analog alpha-TEA and celecoxib alone and together reduce human MDA-MB-435-FL-GFP breast cancer burden and metastasis in nude mice. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004 Sep;87(2):111–21.

88. Van der Auwera I, Van Laere SJ, Van den Eynden GG, Benoy I, van Dam P, Colpaert CG, et al. Increased angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in inflammatory versus noninflammatory breast cancer by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR gene expression quantification. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2004 Dec 1;10(23):7965–71.

89. Pierga JY, Petit T, Delozier T, Ferrero JM, Campone M, Gligorov J, et al. Neoadjuvant bevacizumab, trastuzumab, and chemotherapy for primary inflammatory HER2-positive breast cancer (BEVERLY-2): an open-label, single-arm phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012 Apr;13(4):375–84.

90. Lamalice L, Le Boeuf F, Huot J. Endothelial Cell Migration During Angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007 Mar 30;100(6):782–94.

91. Norton KA, Popel AS. Effects of endothelial cell proliferation and migration rates in a computational model of sprouting angiogenesis. Sci Rep. 2016 Nov 14;6(1):36992.

92. Ausprunk DH, Folkman J. Migration and proliferation of endothelial cells in preformed and newly formed blood vessels during tumor angiogenesis. Microvasc Res. 1977 Jul 1;14(1):53–65.

93. Hahn ME. Aryl hydrocarbon receptors: diversity and evolution. Chem Biol Interact. 2002 Sep 20;141(1–2):131–60.

94. Korkalainen M, Tuomisto J, Pohjanvirta R. The AH receptor of the most dioxin-sensitive species, guinea pig, is highly homologous to the human AH receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001 Aug 3;285(5):1121–9.

95. Cohen-Barnhouse AM, Zwiernik MJ, Link JE, Fitzgerald SD, Kennedy SW, Hervé JC, et al. Sensitivity of Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica), Common pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), and White Leghorn chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) embryos to in ovo exposure to TCDD, PeCDF, and TCDF. Toxicol Sci Off J Soc Toxicol. 2011 Jan;119(1):93–103.

96. Doering JA, Giesy JP, Wiseman S, Hecker M. Predicting the sensitivity of fishes to dioxin-like compounds: possible role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligand binding domain. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2013 Mar;20(3):1219–24.

97. DiNatale BC, Schroeder JC, Francey LJ, Kusnadi A, Perdew GH. Mechanistic insights into the events that lead to synergistic induction of interleukin 6 transcription upon activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and inflammatory signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010 Aug 6;285(32):24388–97.

98. Liu Z, Wu X, Zhang F, Han L, Bao G, He X, et al. AhR expression is increased in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Mol Histol. 2013 Aug;44(4):455–61.

99. Stanford EA, Ramirez-Cardenas A, Wang Z, Novikov O, Alamoud K, Koutrakis P, et al. Role for the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and Diverse Ligands in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Migration and Tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer Res MCR. 2016 Aug;14(8):696–706.

100. Koliopanos A, Kleeff J, Xiao Y, Safe S, Zimmermann A, Büchler MW, et al. Increased arylhydrocarbon receptor expression offers a potential therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 2002 Sep 5;21(39):6059–70.

101. Chang JT, Chang H, Chen PH, Lin SL, Lin P. Requirement of aryl hydrocarbon receptor overexpression for CYP1B1 up-regulation and cell growth in human lung adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2007 Jan 1;13(1):38–45.

102. Moennikes O, Loeppen S, Buchmann A, Andersson P, Ittrich C, Poellinger L, et al. A constitutively active dioxin/aryl hydrocarbon receptor promotes hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Cancer Res. 2004 Jul 15;64(14):4707–10.

103. Ishida M, Mikami S, Shinojima T, Kosaka T, Mizuno R, Kikuchi E, et al. Activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor promotes invasion of clear cell renal cell carcinoma and is associated with poor prognosis and cigarette smoke. Int J Cancer. 2015 Jul 15;137(2):299–310.

104. Ishida M, Mikami S, Kikuchi E, Kosaka T, Miyajima A, Nakagawa K, et al. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway enhances cancer cell invasion by upregulating the MMP expression and is associated with poor prognosis in upper urinary tract urothelial cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010 Feb;31(2):287–95.

105. Diry M, Tomkiewicz C, Koehle C, Coumoul X, Bock KW, Barouki R, et al. Activation of the dioxin/aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) modulates cell plasticity through a JNK-dependent mechanism. Oncogene. 2006 Sep 7;25(40):5570–4.

106. John K, Lahoti TS, Wagner K, Hughes JM, Perdew GH. The Ah receptor regulates growth factor expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Mol Carcinog. 2014 Oct;53(10):765–76.

107. AOP-Wiki [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 15]. Available from: https://aopwiki.org/

108. Brooks J, Eltom SE. Malignant transformation of mammary epithelial cells by ectopic overexpression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011 Jun;11(5):654–69.

109. Currier N, Solomon SE, Demicco EG, Chang DLF, Farago M, Ying H, et al. Oncogenic signaling pathways activated in DMBA-induced mouse mammary tumors. Toxicol Pathol. 2005;33(6):726–37.

110. Pirkle JL, Wolfe WH, Patterson DG, Needham LL, Michalek JE, Miner JC, et al. Estimates of the half-life of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in Vietnam Veterans of Operation Ranch Hand. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1989;27(2):165–71.

111. Pesatori AC, Consonni D, Rubagotti M, Grillo P, Bertazzi PA. Cancer incidence in the population exposed to dioxin after the “Seveso accident”: twenty years of follow-up. Environ Health Glob Access Sci Source. 2009 Sep 15;8:39.

112. Warner M, Eskenazi B, Mocarelli P, Gerthoux PM, Samuels S, Needham L, et al. Serum dioxin concentrations and breast cancer risk in the Seveso Women’s Health Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2002 Jul;110(7):625–8.

Fulda, S., & Debatin, K. M. (2007). Apoptosis signaling in cancer. Experimental Cell Research, 313(9), 1503-1515. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17296041/

Hanahan, D., & Weinberg, R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell, 144(5), 646-674. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5446472/

Luo, X., & Heng, H. H. (2003). Apoptosis and cancer therapy: lessons from the past and new directions. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 9(21), 1803-1816. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14574468/

Schmitt, C. A., et al. (2000). Senescence and apoptosis. Oncogene, 19(56), 6207-6210. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11101894/

Benson, A. B., et al. (2008). Tumor size and stage in colon and rectal cancer: Consistent prognostic factors over time. Annals of Surgery, 247(3), 421-429.

Clark, B. A., et al. (2009). New insights into the biology of human malignant melanoma. Annual Review of Medicine, 60, 361-377. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19021562/

Friedl, P., & Weigelin, B. (2008. Interstitial cell migration and invasion in cancer and metastasis. Nature Reviews Cancer, 8(10), 700-710. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2724717/

Fearon, E. R., & Vogelstein, B. (1990). A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell, 61(5), 759-767. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2202721/

Olive, P. L., et al. (2009. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine. Clinical Cancer Research, 15(8), 2553-2562. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19318265/

Appendix 1

List of MIEs in this AOP

Event: 18: Activation, AhR

Short Name: Activation, AhR

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity | aryl hydrocarbon receptor | increased |

AOPs Including This Key Event

Stressors

| Name |

|---|

| Benzidine |

| Dibenzo-p-dioxin |

| Polychlorinated biphenyl |

| Polychlorinated dibenzofurans |

| Hexachlorobenzene |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) |

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Molecular |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| zebra danio | Danio rerio | High | NCBI |

| Gallus gallus | Gallus gallus | High | NCBI |

| Pagrus major | Pagrus major | High | NCBI |

| Acipenser transmontanus | Acipenser transmontanus | High | NCBI |

| Acipenser fulvescens | Acipenser fulvescens | High | NCBI |

| rainbow trout | Oncorhynchus mykiss | High | NCBI |

| Salmo salar | Salmo salar | High | NCBI |

| Xenopus laevis | Xenopus laevis | High | NCBI |

| Ambystoma mexicanum | Ambystoma mexicanum | High | NCBI |

| Phasianus colchicus | Phasianus colchicus | High | NCBI |

| Coturnix japonica | Coturnix japonica | High | NCBI |

| mouse | Mus musculus | High | NCBI |

| rat | Rattus norvegicus | High | NCBI |

| human | Homo sapiens | High | NCBI |

| Microgadus tomcod | Microgadus tomcod | High | NCBI |

| Homo sapiens | Homo sapiens | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Embryo | High |

| Development | High |

| All life stages | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Unspecific | High |

The AHR structure has been shown to contribute to differences in species sensitivity to DLCs in several animal models. In 1976, a 10-fold difference was reported between two strains of mice (non-responsive DBA/2 mouse, and responsive C57BL/6 14 mouse) in CYP1A induction, lethality and teratogenicity following TCDD exposure[3]. This difference in dioxin sensitivity was later attributed to a single nucleotide polymorphism at position 375 (the equivalent position of amino acid residue 380 in chicken) in the AHR LBD[30][19][31]. Several other studies reported the importance of this amino acid in birds and mammals[32][30][22][33][34][35][31][36]. It has also been shown that the amino acid at position 319 (equivalent to 324 in chicken) plays an important role in ligand-binding affinity to the AHR and transactivation ability of the AHR, due to its involvement in LBD cavity volume and its steric effect[35]. Mutation at position 319 in the mouse eliminated AHR DNA binding[35].

The first study that attempted to elucidate the role of avian AHR1 domains and key amino acids within avian AHR1 in avian differential sensitivity was performed by Karchner et al.[22]. Using chimeric AHR1 constructs combining three AHR1 domains (DBD, LBD and TAD) from the chicken (highly sensitive to DLC toxicity) and common tern (resistant to DLC toxicity), Karchner and colleagues[22], showed that amino acid differences within the LBD were responsible for differences in TCDD sensitivity between the chicken and common tern. More specifically, the amino acid residues found at positions 324 and 380 in the AHR1 LBD were associated with differences in TCDD binding affinity and transactivation between the chicken (Ile324_Ser380) and common tern (Val324_Ala380) receptors[22]. Since the Karchner et al. (2006) study was conducted, the predicted AHR1 LBD amino acid sequences were been obtained for over 85 species of birds and 6 amino acid residues differed among species[14][37] . However, only the amino acids at positions 324 and 380 in the AHR1 LBD were associated with differences in DLC toxicity in ovo and AHR1-mediated gene expression in vitro[14][37][16]. These results indicate that avian species can be divided into one of three AHR1 types based on the amino acids found at positions 324 and 380 of the AHR1 LBD: type 1 (Ile324_Ser380), type 2 (Ile324_Ala380) and type 3 (Val324_Ala380)[14][37][16].

- Little is known about differences in binding affinity of AhRs and how this relates to sensitivity in non-avian taxa.

- Low binding affinity for DLCs of AhR1s of African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) and axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) has been suggested as a mechanism for tolerance of these amphibians to DLCs (Lavine et al 2005; Shoots et al 2015).

- Among reptiles, only AhRs of American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) have been investigated and little is known about the sensitivity of American alligator or other reptiles to DLCs (Oka et al 2016).

- Among fishes, great differences in sensitivity to DLCs are known both for AhRs and for embryos among species that have been tested (Doering et al 2013; 2014).

- Differences in binding affinity of the AhR2 have been demonstrated to explain differences in sensitivity to DLCs between sensitive and tolerant populations of Atlantic Tomcod (Microgadus tomcod) (Wirgin et al 2011).

- This was attributed to the rapid evolution of populations in highly contaminated areas of the Hudson River, resulting in a 6-base pair deletion in the AHR sequence (outside the LBD) and reduced ligand binding affinity, due to reduces AHR protein stability.

- Information is not yet available regarding whether differences in binding affinity of AhRs of fishes are predictive of differences in sensitivity of embryos, juveniles, or adults (Doering et al 2013).

The AhR is a very conserved and ancient protein (95) and the AhR is present in human and mice (96–98). The AhR is present in human physiology and pathology. The AhR is highly expressed at several important physiological barriers such as the placenta, lung, gastrointestinal system, and liver in human (Wakx, Marinelli, Watanabe). In these tissues, the AhR is involved in both detoxication processes involving xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes such as cytochromes P450, and in immune functions translating chemical signals into immune defence pathways (Marinelli, Stobbe). Moreover, it has a regulatory role in human dendritic cells and myelination (Kado, Shackleford). The lung constitutes another barrier exposed to components of air pollution such as particles and hydrocarbons (air pollution, cigarette smoke). The AhR detects such hydrocarbons and protects the pulmonary cells from their deleterious effects through metabolization. The regulatory effect on blood cells of the AhR, balancing different related cell types, can be extended to the megakaryocytes and their precursors; indeed, StemRegenin 1 (SR1), an antagonist of the AhR increases the human population of CD34+CD41low cells, a fraction of very efficient precursors of proplatelets (Bock). The occurrence of a nystagmus has been subsequently diagnosed in humans bearing a AhR mutation (Borovok).

In human cancer, the AhR has either a pro or con tumor effect depending on the tissue, the ligand, and the duration of the activation (Zudaire, Chang, Litzenburg, Gramatzki, Lin, Wang). In human breast cancer, the AhR is thoughts to be responsible of its progression (Goode, Kanno, Optiz, Novikov, Hall, Subramaniam, Barhoover). In human mammary benign cells, Brooks et al. noted that a high level of AhR was associated with a modified cell cycle (with a 50% increase in population doubling time in cells expressing the AhR by more than 3-fold) and EMT including increased cell migration. Narasimnhan et al. found that suppression of the AhR pathway had a pro-tumorigenic effect in vitro (EMT, tumor migration) in triple negative breast cancer.

Many endogenous and exogenous ligands are present for the AhR in human (Optiz, Adachi, Schroeder, Rothhammer). Indoles, such as indole-3-carbinol or one of its secondary metabolites, 3-3'- Diindolylmethane, are degradation products found in cruciferous vegetables and characterized as AhR ligands (Ema, Kall, Miller) they are also inducers of the human and rat CYP1A1 (Optiz). FICZ is the most potent AhR ligand known to date: it has a stronger affinity than TCDD for the human AhR (TCDD Kd=0.48 nM/FICZ Kd=0.07 nM) (Coumoul).

Key Event Description

The AHR Receptor

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that belongs to the basic helix-loop-helix Per-ARNT-Sim (bHLH-PAS) superfamily and consists of three domains: the DNA-binding domain (DBD), ligand binding domain (LBD) and transactivation domain (TAD)[1]. Other members of this superfamily include the AHR nuclear translocator (ARNT), which acts as a dimerization partner of the AHR [2][3]; Per, a circadian transcription factor; and Sim, the “single-minded” protein involved in neuronal development [4][5]. This group of proteins shares a highly conserved PAS domain and is involved in the detection of and adaptation to environmental change[4].

Investigations of invertebrates possessing early homologs of the AhR suggest that the AhR evolutionarily functioned in regulation of the cell cycle, cellular proliferation and differentiation, and cell-to-cell communications (Hahn et al 2002). However, critical functions in angiogenesis, regulation of the immune system, neuronal processes, metabolism, development of the heart and other organ systems, and detoxification have emerged sometime in early vertebrate evolution (Duncan et al., 1998; Emmons et al., 1999; Lahvis and Bradfield, 1998).

The molecular Initiating Event

The molecular mechanism for AHR-mediated activation of gene expression is presented in Figure 1. In its unliganded form, the AHR is part of a cytosolic complex containing heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), the HSP90 co-chaperone p23 and AHR-interacting protein (AIP)[6]. Upon ligand binding, the AHR migrates to the nucleus where it dissociates from the cytosolic complex and forms a heterodimer with ARNT[7]. The AHR-ARNT complex then binds to a xenobiotic response element (XRE) found in the promoter of an AHR-regulated gene and recruits co-regulators such as CREB binding protein/p300, steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) 1, SRC-2, SRC-3 and nuclear receptor interacting protein 1, leading to induction or repression of gene expression[6]. Expression levels of several genes, including phase I (e.g. cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A, CYP1B, CYP2A) and phase II enzymes (e.g. uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase (UDP-GT), glutathione S-transferases (GSTs)), as well as genes involved in cell proliferation (transforming growth factor-beta, interleukin-1 beta), cell cycle regulation (p27, jun-B) and apoptosis (Bax), are regulated through this mechanism [6][8][7][9].

AHR Isoforms

- Over time the AhR has undergone gene duplication and diversification in vertebrates, which has resulted in multiple clades of AhR, namely AhR1, AhR2, and AhR3 (Hahn 2002).

- Fishes and birds express AhR1s and AhR2s, while mammals express a single AhR that is homologous to the AhR1 (Hahn 2002; Hahn et al 2006).

- The AhR3 is poorly understood and known only from some cartilaginous fishes (Hahn 2002).

- Little is known about diversity of AhRs in reptiles and amphibians (Hahn et al 2002).

- In some taxa, subsequent genome duplication events have further led to multiple isoforms of AhRs in some species, with up to four isoforms of the AhR (α, β, δ, γ) having been identified in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) (Hansson et al 2004).