AOP ID and Title:

Graphical Representation

Status

| Author status | OECD status | OECD project | SAAOP status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under development: Not open for comment. Do not cite |

Abstract

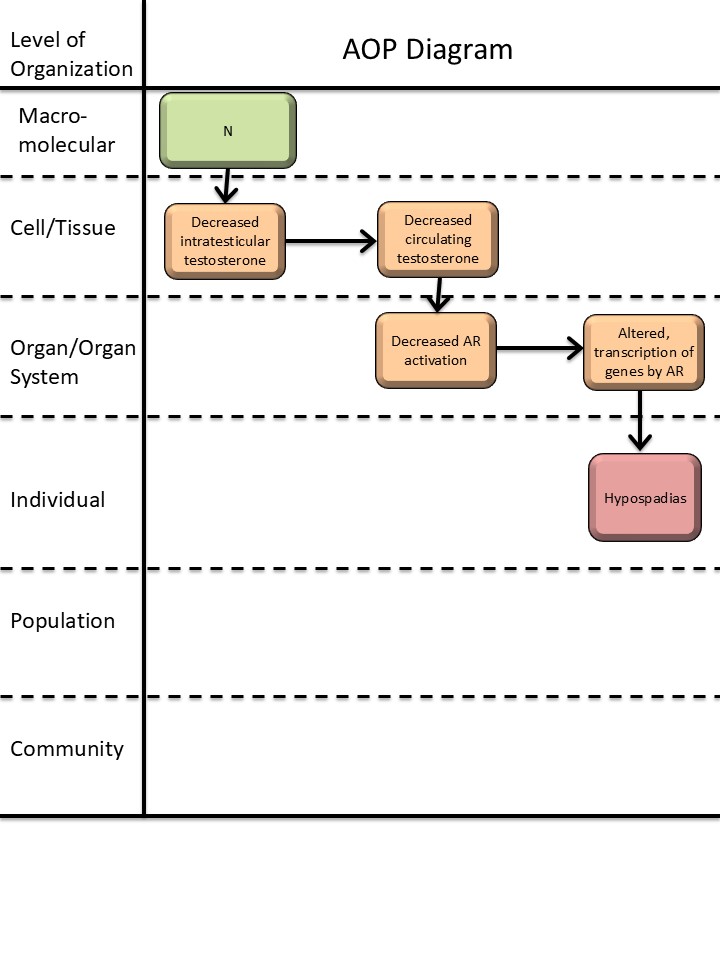

This AOP links in utero decreased intratesticular testosterone levels with hypospadias in male offspring. Hypospadias is a common reproductive disorder with a prevalence of up to ~1/125 newborn boys (Leunbach et al., 2025; Paulozzi, 1999). Developmental exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals is suspected to contribute to some cases of hypospadias (Mattiske & Pask, 2021). Hypospadias can be indicative of fetal disruptions to male reproductive development, and is associated with short anogenital distance and cryptorchidism (Skakkebaek et al., 2016). Thus, hypospadias is included as an endpoint in OECD test guidelines (TG) for developmental and reproductive toxicity (TG 414, 416, 421/422, and 443; (OECD, 2001, 2016b, 2016a, 2018a, 2018b)), as both a measurement of adverse reproductive effects and a direct clinical adverse outcome.

Testosterone is one of the two main steroid sex hormones essential for male reproductive development. Testosterone is primarily, but not exclusively, produced in the testes and then secreted into the circulation. In peripheral reproductive tissues, testosterone is either converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) or directly activates the androgen receptor (AR). DHT is more potent than testosterone in activating the AR, and activation of AR by either androgen initiates differentiation of the male phenotype, including development of the penis (Amato et al., 2022; Davey & Grossmann, 2016). This AOP delineates the evidence that decreasing testicular testosterone production lowers circulating testosterone levels and consequently AR activation, thereby disrupting penis development and causing hypospadias. In this AOP, the first KE is not considered an MIE, as testicular testosterone production can be obstructed by various routes. The AOP does not discriminate whether the reduction in AR activation is due to direct lack of testosterone at the AR or due to decreased conversion of testosterone to DHT, as there is not sufficient information on this. The AOP is supported by in vitro experiments upstream of AR activation and by in vivo and human case studies downstream of AR activation. Downstream of a reduction in AR activation, the molecular mechanisms of hypospadias development are not fully delineated, highlighting a knowledge gap in this AOP. Thus, the AOP has potential for inclusion of additional KEs and elaboration of molecular causality links, once these are established. Given that hypospadias is both a clinical and toxicological endpoint, this AOP is considered highly relevant in a regulatory context.

Background

This AOP is a part of an AOP network for reduced androgen receptor activation causing hypospadias in male offspring. The other AOPs in this network are AOP-477 (‘Androgen receptor antagonism leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring’), and AOP-571 (‘5α-reductase inhibition leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring’). The purpose of the AOP network is to organize the well-established evidence for anti-androgenic mechanisms-of-action leading to hypospadias, thus informing predictive toxicology and identifying knowledge gaps for investigation and method development.

This work received funding from the European Food and Safety Authority (EFSA) under Grant agreement no. GP/EFSA/PREV/2022/01 and from the Danish Environmental Protection Agency under the Danish Center for Endocrine Disrupters (CeHoS).

Summary of the AOP

Events

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE), Key Events (KE), Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Sequence | Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KE | 2298 | Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels | Decrease, intratesticular testosterone | |

| KE | 1690 | Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | |

| KE | 1614 | Decrease, androgen receptor activation | Decrease, AR activation | |

| KE | 286 | Altered, Transcription of genes by the androgen receptor | Altered, Transcription of genes by the AR | |

| AO | 2082 | Hypospadias, increased | Hypospadias |

Key Event Relationships

| Upstream Event | Relationship Type | Downstream Event | Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels | adjacent | Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | High | |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | adjacent | Decrease, androgen receptor activation | High | |

| Decrease, androgen receptor activation | adjacent | Altered, Transcription of genes by the androgen receptor | High | |

| Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels | non-adjacent | Hypospadias, increased | Moderate | |

| Decrease, circulating testosterone levels | non-adjacent | Hypospadias, increased | Low | |

| Decrease, androgen receptor activation | non-adjacent | Hypospadias, increased | High |

Stressors

| Name | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Dibutyl phthalate | |

| Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate |

Overall Assessment of the AOP

Domain of Applicability

Life Stage Applicability| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Foetal | High |

| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| human | Homo sapiens | High | NCBI |

| rat | Rattus norvegicus | High | NCBI |

| mouse | Mus musculus | Moderate | NCBI |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

Although the upstream part of the AOPN has a broad applicability domain, the overall AOPN is considered only applicable to male mammals during fetal life, restricted by the applicability of KE-2298 (‘Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels’) and KER-3488 (‘Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels leads to hypospadias’), KER-3350 (‘Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to hypospadias’), and KER-2828 (‘Decrease AR activation leads to hypospadias’). By definition, testes are the primary sex organs in males, and the term hypospadias is mainly used for describing malformation of the male and not female external genitalia. The genital tubercle is programmed by androgens to differentiate into a penis in fetal life in the masculinization programming window, followed by the morphological differentiation (Welsh et al., 2008). In humans, hypospadias is diagnosed at birth and can also often be observed in rodents at this time point, although the rodent penis does not finish developing until a few weeks after birth (Baskin & Ebbers, 2006; Sinclair et al., 2017). The disruption to androgen programming leading to hypospadias thus happens in the fetal life stage, but the AO is best detected postnatally. Regarding taxonomic applicability, hypospadias has mainly been identified in rodents (rats and mice) and humans, and the evidence in this AOP is almost exclusively from these species. It is, however, biologically plausible that the AOP is applicable to other mammals as well, given the conserved role of androgens in mammalian reproductive development, and hypospadias has been observed in many domestic animal and wildlife species, albeit not coupled to reduced testosterone levels.

Essentiality of the Key Events

|

Event |

Evidence |

Uncertainties and inconsistencies |

|

KE-2298 Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels (moderate) |

Biological plausibility provides strong support for the essentiality of this event as the testes are the main sites of testosterone production in male mammals, and testosterone is a ligand for the AR and one of the primary drivers of penis development.

Experimental evidence with phthalates lowering intratesticular testosterone supports the essentiality (see KE 3488)

Human case studies indirectly support the essentiality as mutations in steroidogenesis enzymes and gonadal dysgenesis are associated with low circulating testosterone levels and hypospadias (as listed in table 4, KER 2828) |

In the human studies, testosterone levels were only measured postnatally and not in fetal life. |

|

KE-1690 Decrease, circulating testosterone levels (moderate) |

Biological plausibility provides strong support for the essentiality of this event as testosterone is a ligand for the AR and one of the primary drivers of penis development

Human case studies support the essentiality as low circulating testosterone levels have been associated with hypospadias (as listed in table 4 in KER-2828). |

In human case studies, testosterone levels were only measured postnatally and not in fetal life. As hypospadias is a congenital malformation, it cannot be “reversed” by testosterone treatment. |

|

KE-1614 Decrease, AR activation (moderate) |

Biological plausibility provides strong support for the essentiality of this event, as AR activation is critical for normal penis development.

Conditional or full knockout of Ar in mice results in partly or full sex-reversal of males, including a female-like urethral opening (Willingham et al., 2006; Yucel et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2015). Human subjects with AR mutations may also have associated hypospadias (as presented in table 4 in KER 2828). |

|

|

KE-286 Altered, transcription of genes by AR (low) |

Biological plausibility provides support for the essentiality of this event. AR is a nuclear receptor and transcription factor regulating transcription of genes, and androgens, acting through AR, are essential for normal male penis development. Known AR-responsive genes active in normal penis development have been thoroughly reviewed (Amato et al., 2022). |

There are currently no AR-responsive genes proved to be causally involved in hypospadias, and it is known that the AR can also signal through non-genomic actions (Leung & Sadar, 2017). |

|

Event |

Direct evidence |

Indirect evidence |

Contradictory evidence |

Overall essentiality assessment |

|

KE-2298 |

|

** |

* |

Moderate |

|

KE-1690 |

|

*** |

* |

Moderate |

|

KE-1614 |

** |

|

|

Moderate |

|

KE-286 |

|

* |

|

Low |

Weight of Evidence Summary

The confidence in each of the KERs comprising the AOP are judged as high, with both high biological plausibility and high confidence in the empirical evidence. The mechanistic link between KE-286 (‘altered, transcription of genes by AR’) and AO-2082 (‘hypospadias’) is not established, but given the high confidence in the KERs including the non-adjacent KER-2828 linking to the AO, the overall confidence in the AOP is judged as high.

|

KER |

Biological Plausibility |

Empirical Evidence |

Rationale |

|

KER-3448 Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels leads to decrease, circulating testosterone levels |

High |

High (canonical) |

It is well established that testes are the primary testosterone-producing organs in male mammals. In vivo studies have shown that exposure to substances that lowers intratesticular testosterone also lowers circulating testosterone levels (Svingen et al., 2025). |

|

KER-2131 Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to decrease, AR activation |

High |

High (canonical) |

It is well established that testosterone activates the AR. Direct evidence for this KER is not possible since KE 1614 can currently not be measured and is considered an in vivo effect. Indirect evidence using proxy read-outs of AR activation, either in vitro or in vivo strongly supports the relationship (Draskau et al., 2024). |

|

KER-2124 Decrease, AR activation leads to altered, transcription of genes by AR |

High |

High (canonical) |

It is well established that the AR regulates gene transcription. In vivo animal studies and human genomic profiling show tissue-specific changes to gene expression upon disruption of AR (Draskau et al., 2024). |

|

KER-3488 Decrease, intratesticular testosterone leads to hypospadias |

High |

Moderate |

It is well established that testicular testosterone is one of the primary drivers of penis development. In vivo animal studies support that reductions in fetal testicular testosterone can cause hypospadias in male offspring. One study supports dose concordance, where diisocytol caused reduced ex vivo testosterone production in rats at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg bw/day, while hypospadias was observed in male offspring at 1 mg/kg bw/day (Saillenfait et al., 2013). |

|

KER-3350 Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to hypospadias |

High |

Low |

It is well established that testosterone is one of the primary drivers of penis development. In vivo evidence for this KER is sparse, but human case studies of subjects with low testosterone levels (postnatally) and associated hypospadias support the KER.

|

|

KER-2828 Decrease, AR activation leads to hypospadias |

High |

High |

It is well established that AR drives penis differentiation. Numerous in vivo toxicity studies and human case studies indirectly show that decreased AR activation leads to hypospadias, with few inconsistencies. The empirical evidence moderately supports dose, temporal, and incidence concordance for the KER. |

Quantitative Consideration

The quantitative understanding of this AOP is judged as low.

A model for phthalate-induced malformations has been developed which aims to predict the frequency of hypospadias related to a phthalate’s reduction in ex vivo testosterone production. The model predicted that a 60% reduction in testosterone levels would induce hypospadias, although the predictivity of this model was not good when tested for one phthalate (Earl Gray et al., 2024).

References

Amato, C. M., Yao, H. H.-C., & Zhao, F. (2022). One Tool for Many Jobs: Divergent and Conserved Actions of Androgen Signaling in Male Internal Reproductive Tract and External Genitalia. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13, 910964. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.910964

Baskin, L., & Ebbers, M. (2006). Hypospadias: Anatomy, etiology, and technique. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 41(3), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.059

Bhasin, S., Cunningham, G. R., Hayes, F. J., Matsumoto, A. M., Snyder, P. J., Swerdloff, R. S., & Montori, V. M. (2010). Testosterone Therapy in Men with Androgen Deficiency Syndromes: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 95(6), 2536–2559. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-2354

Chamberlain, N. L., Driver, E. D., & Miesfeld, R. L. (1994). The length and location of CAG trinucleotide repeats in the androgen receptor N-terminal domain affect transactivation function. Nucleic Acids Research, 22(15), 3181–3186. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.15.3181

Coviello, A. D., Bremner, W. J., Matsumoto, A. M., Herbst, K. L., Amory, J. K., Anawalt, B. D., Yan, X., Brown, T. R., Wright, W. W., Zirkin, B. R., & Jarow, J. P. (2004). Intratesticular Testosterone Concentrations Comparable With Serum Levels Are Not Sufficient to Maintain Normal Sperm Production in Men Receiving a Hormonal Contraceptive Regimen. Journal of Andrology, 25(6), 931–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb03164.x

Davey, R. A., & Grossmann, M. (2016). Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. The Clinical Biochemist. Reviews, 37(1), 3–15.

Draskau, M., Rosenmai, A., Bouftas, N., Johansson, H., Panagiotou, E., Holmer, M., Elmelund, E., Zilliacus, J., Beronius, A., Damdimopoulou, P., van Duursen, M., & Svingen, T. (2024). Aop Report: An Upstream Network for Reduced Androgen Signalling Leading to Altered Gene Expression of Ar Responsive Genes in Target Tissues. Environ Toxicol Chem, In Press.

Earl Gray, L. J., Lambright, C. S., Evans, N., Ford, J., & Conley, J. M. (2024). Using targeted fetal rat testis genomic and endocrine alterations to predict the effects of a phthalate mixture on the male reproductive tract. Current Research in Toxicology, 7, 100180–100180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2024.100180

Holmer, M. L., Zilliacus, J., Draskau, M. K., Hlisníková, H., Beronius, A., & Svingen, T. (2024). Methodology for developing data-rich Key Event Relationships for Adverse Outcome Pathways exemplified by linking decreased androgen receptor activity with decreased anogenital distance. Reproductive Toxicology, 128, 108662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2024.108662

Leunbach, T. L., Berglund, A., Ernst, A., Hvistendahl, G. M., Rawashdeh, Y. F., & Gravholt, C. H. (2025). Prevalence, Incidence, and Age at Diagnosis of Boys With Hypospadias: A Nationwide Population-Based Epidemiological Study. Journal of Urology, 213(3), 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000004319

Leung, J. K., & Sadar, M. D. (2017). Non-Genomic Actions of the Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00002

Mattiske, D. M., & Pask, A. J. (2021). Endocrine disrupting chemicals in the pathogenesis of hypospadias; developmental and toxicological perspectives. Current Research in Toxicology, 2, 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2021.03.004

McLachlan, R. I., O’Donnell, L., Stanton, P. G., Balourdos, G., Frydenberg, M., de Kretser, D. M., & Robertson, D. M. (2002). Effects of Testosterone Plus Medroxyprogesterone Acetate on Semen Quality, Reproductive Hormones, and Germ Cell Populations in Normal Young Men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 87(2), 546–556. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.87.2.8231

OECD. (2001). Test No. 416: Two-Generation Reproduction Toxicity [OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4]. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264070868-en

OECD. (2016a). Test No. 421: Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264264380-en

OECD. (2016b). Test No. 422: Combined Repeated Dose Toxicity Study with the Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264264403-en

OECD. (2018a). Test No. 414: Prenatal Developmental Toxicity Study. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264070820-en

OECD. (2018b). Test No. 443: Extended One-Generation Reproductive Toxicity Study. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264185371-en

Paulozzi, L. J. (1999). International trends in rates of hypospadias and cryptorchidism.

Saillenfait, A., Sabaté, J., Robert, A., Cossec, B., Roudot, A., Denis, F., & Burgart, M. (2013). Adverse effects of diisooctyl phthalate on the male rat reproductive development following prenatal exposure. Reproductive Toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.), 42, 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.09.004

Sinclair, A., Cao, M., Pask, A., Baskin, L., & Cunha, G. (2017). Flutamide-induced hypospadias in rats: A critical assessment. Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity, 94, 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2016.12.001

Skakkebaek, N. E., Rajpert-De Meyts, E., Louis, G. M. B., Toppari, J., Andersson, A.-M., Eisenberg, M. L., Jensen, T. K., Jorgensen, N., Swan, S. H., Sapra, K. J., Ziebe, S., Priskorn, L., & Juul, A. (2016). Male Reproductive Disorders And Fertility Trends: Influences Of Environement And Genetic susceptibility. PHYSIOLOGICAL REVIEWS, 96(1), 55–97. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00017.2015

Svingen, T., Elmelund, E., Holmer, M. L., Bindel, A. O., Holbech, H., & Draskau, M. K. (2025). AOP report: Adverse Outcome Pathway Network for Developmental Androgen Signalling-Inhibition Leading to Short Anogenital Distance in Male Offspring. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, vgaf221. https://doi.org/10.1093/etojnl/vgaf221

Svingen, T., Villeneuve, D. L., Knapen, D., Panagiotou, E. M., Draskau, M. K., Damdimopoulou, P., & O’Brien, J. M. (2021). A Pragmatic Approach to Adverse Outcome Pathway Development and Evaluation. Toxicological Sciences, 184(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfab113

Turner, T. T., Jones, C. E., Howards, S. S., Ewing, L. L., Zegeye, B., & Gunsalus, G. L. (1984). On the androgen microenvironment of maturing spermatozoa. Endocrinology, 115(5), 1925–1932. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-115-5-1925

Tut, T. G., Ghadessy, F. J., Trifiro, M. A., Pinsky, L., & Yong, E. L. (1997). Long Polyglutamine Tracts in the Androgen Receptor Are Associated with Reduced Trans -Activation, Impaired Sperm Production, and Male Infertility 1. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 82(11), 3777–3782. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.82.11.4385

Welsh, M., Saunders, P. T. K., Fisken, M., Scott, H. M., Hutchison, G. R., Smith, L. B., & Sharpe, R. M. (2008). Identification in rats of a programming window for reproductive tract masculinization, disruption of which leads to hypospadias and cryptorchidism. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 118(4), 1479–1490. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI34241

Willingham, E., Agras, K., Souza, A. J. de, Konijeti, R., Yucel, S., Rickie, W., Cunha, G., & Baskin, L. (2006). Steroid receptors and mammalian penile development: An unexpected role for progesterone receptor? The Journal of Urology, 176(2), 728–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.078

Yucel, S., Liu, W., Cordero, D., Donjacour, A., Cunha, G., & Baskin, L. (2004). Anatomical studies of the fibroblast growth factor-10 mutant, Sonic Hedge Hog mutant and androgen receptor mutant mouse genital tubercle. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 545, 123–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8995-6_8

Zheng, Z., Armfield, B., & Cohn, M. (2015). Timing of androgen receptor disruption and estrogen exposure underlies a spectrum of congenital penile anomalies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(52), E7194-203. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1515981112

Appendix 1

List of Key Events in the AOP

Event: 2298: Decrease, intratesticular testosterone levels

Short Name: Decrease, intratesticular testosterone

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| testosterone biosynthetic process | testosterone | decreased |

AOPs Including This Key Event

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Organ |

Organ term

| Organ term |

|---|

| testis |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability Life Stage Applicability| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

This key event (KE) is applicable to all male vertebrates with testis that produce testosterone.

Key Event Description

This KE refers to decreased testosterone biosynthesis in the testis (male); i.e. intratesticular testosterone levels. It is therefore considered distinct from KEs describing circulating testosterone levels, or levels in any other tissue or organ of vertebrate animals. It is also distinct from indirect cell-based assays measuring effects on testosterone synthesis, including in vitro Leydig cells.

In males, the testis is the primary site of testosterone biosynthesis via the steroidogenesis pathway – an enzymatic pathway converting cholesterol into all the downstream steroid hormones (Miller and Auchus 2010). In mammals, the Leydig cells are considered the primary site of steroidogenesis in the testis. Although generally correct, there is evidence to suggest the involvement of Sertoli cells during fetal stages in e.g. mouse and human testis, but with Leydig cells being sufficient in adult life (O’Donnell et al 2022).

Testicular testosterone synthesis is primarily regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, with Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus controlling the secretion of Luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary that ultimately binds to the LH receptors on Leydig cells to stimulate steroidogenesis. Notably, the timing of HPG axis activation during development varies between species. In humans, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) act similarly to LH and appear to be critical in stimulating testosterone synthesis in the fetal testis (Huhtaniemi 2025), whereas in the mouse testosterone synthesis in the fetal testis appears to be independent of pituitary gonadotropins even though LH is detectable during late gestation O’Shaughnessy et al 1998). Irrespective of testosterone being stimulated by gonadotropins or occurring de novo, however, it is essential for masculinization of the developing fetus, initiation of puberty, and maintain reproductive, and other, functions in adulthood.

Notably, intratesticular testosterone concentration is significantly higher than serum testosterone levels, typically ranging from 30- to 200-fold greater in mammals, including humans (Turner et al 1984; McLachlan et al 2002; Coviello et al 2004).

How it is Measured or Detected

Testosterone levels can be quantified in testis tissue (ex vivo, in vivo). Methods include traditional immunoassays such as ELISA and RIA, advanced techniques like LC-MS/MS, and liquid scintillation spectrometry following radiolabeling (Shiraishi et al., 2008).

References

Coviello, A.D., Bremner, W.J., Matsumoto, A.M., Herbst, K.L., Amory, J.K., Anawalt, B.D., Yan, X., Brown, T.R., Wright, W.W., Zirkin, B.R. and Jarow, J.P. (2004). Intratesticular Testosterone Concentrations Comparable With Serum Levels Are Not Sufficient to Maintain Normal Sperm Production in Men Receiving a Hormonal Contraceptive Regimen. J Androl, 25:931-938. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb03164.x

Huhtaniemi, I.T. (2025). Luteinizing hormone receptor knockout mouse: What has it taught us? Andrology, In Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.70000

McLachlan, R.I., O’Donnell, L., Stanton, P.G., Balourdos, G., Frydenberg, M., de Kretser, D.M. and Robertson, D.M. (2002). Effects of testosterone plus medroxyprogesterone acetate on semen quality, reproductive hormones, and germ cell populations in normal young men. J Clin Endocriol Metab, 87:546-556. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.87.2.8231

Miller, W.L. and Auchus, R.J. (2010). The Molecular Biology, Biochemistry, and Physiology of Human Steroidogenesis and Its Disorders. Endocr Rev, 32(1):81-151. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2010-0013

O’Donnell, L., Whiley, P.A.F., and Loveland, K.L. (2022). Activin A and Sertoli Cells: Key to Fetal Testis Steroidogenesis. Front Endocrinol, 13:898876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.898876

O’Shaughnessy, P.J., Baker, P., Sohnius, U., Haavisto, A.M., Charlton, H.M. and Huhtaniemi, I. (1998). Fetal development of Leydig cell activity in the mouse is independent of pituitary gonadotroph function. Endocrinology, 139:1141-1146. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.139.3.5788

Shiraishi, S., Lee, P. W. N., Leung, A., Goh, V. H. H., Swerdloff, R. S., & Wang, C. (2008). Simultaneous Measurement of Serum Testosterone and Dihydrotestosterone by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Clinical Chemistry, 54(11), 1855–1863. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2008.103846

Turner, T.T., Jones, C.E., Howards, S.S., Ewing, L.L., Zegeye, B. and Gunsalus, G.L. (1984). On the androgen microenvironment of maturing spermatozoa. Endocrinology, 115:1925-1932. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-115-5-1925

Event: 1690: Decrease, circulating testosterone levels

Short Name: Decrease, circulating testosterone levels

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| hormone biosynthetic process | testosterone | decreased |

| testosterone biosynthetic process | testosterone | decreased |

AOPs Including This Key Event

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Tissue |

Organ term

| Organ term |

|---|

| blood |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

| Female | High |

This key event (KE) is applicable to all mammals, as the synthesis and role of testosterone are evolutionarily conserved (Vitousek et al., 2018). Both sexes produce and require testosterone, which plays critical roles throughout life, from development to adulthood; albeit there are differences in lief stages when testosterone exert specific effects and function (Luetjens & Weinbauer, 2012; Naamneh Elzenaty et al., 2022). Accordingly, this KE applies to both males and females across all life stages, but life stage should be considered when embedding in AOPs.

Notably, the key enzymes involved in testosterone production first appeared in the common ancestor of amphioxus and vertebrates (Baker, 2011). This suggests that the KE has a broader domain of applicability, encompassing non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to integrate additional knowledge to expand its relevance beyond mammals to other vertebrates.

Key Event Description

Testosterone is an endogenous steroid hormone that acts by binding the androgen receptor (AR) in androgen-responsive tissues (Murashima et al., 2015). As with all steroid hormones, testosterone is produced through steroidogenesis, an enzymatic pathway converting cholesterol into all the downstream steroid hormones. Briefly, androstenedione or androstenediol is converted to testosterone by the enzymes 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) or 3β-HSD, respectively. Testosterone can then be converted to the more potent androgen, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by 5α-reductase, or aromatized by CYP19A1 (Aromatase) into estrogens. Testosterone secreted in blood circulation can be found free or bound to SHBG or albumin (Trost & Mulhall, 2016).

Testosterone is produced mainly by the testes (in males), ovaries (in females) and to a lesser degree in the adrenal glands. The output of testosterone from different tissues varies with life stages. During fetal development testosterone is crucial for the differentiation of male reproductive tissues and the overall male phenotype. In adulthood, testosterone synthesis is controlled by the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. GnRH is released from the hypothalamus inducing LH pulses secreted by the anterior pituitary. This LH surge leads to increased testosterone production, both in testes (males) and ovaries (females). If testosterone reaches low levels, this axis is once again stimulated to increase testosterone synthesis. This feedback loop is essential for maintenance of appropriate testosterone levels (Chandrashekar & Bartke, 1998; Ellis et al., 1983; Rey, 2021).

By disrupting e.g. steroidogenesis or the HPG-axis, testosterone synthesis or homeostasis may be disrupted and can lead to less testosterone being synthesized and released into circulation.

General role in biology

Androgens are essential hormones responsible for the development of the male phenotype during fetal life and for sexual maturation at puberty. In adulthood, androgens remain essential for the maintenance of male reproductive function and behavior but is also essential for female fertility. Apart from their effects on reproduction, androgens affect a wide variety of non-reproductive tissues such as skin, bone, muscle, and brain (Heemers et al 2006). Androgens, principally testosterone and DHT, exert most of their effects by interacting with the AR (Murashima et al 2015).

How it is Measured or Detected

Testosterone levels can be quantified in serum (in vivo), cell culture medium (in vitro), or tissue (ex vivo, in vitro). Methods include traditional immunoassays such as ELISA and RIA, advanced techniques like LC-MS/MS, and liquid scintillation spectrometry following radiolabeling (Shiraishi et al., 2008).

The H295R Steroidogenesis Assay (OECD TG 456) is (currently; anno 2025) primarily used to measure estradiol and testosterone production. This validated OECD test guideline uses adrenal H295R cells, with hormone levels measured in the cell culture medium (OECD, 2011). H295R adrenocortical carcinoma cells express the key enzymes and hormones of the steroidogenic pathway, enabling broad analysis of steroidogenesis disruption by quantifying hormones in the medium using LC-MS/MS. Initially designed to assess testosterone and estradiol levels, the assay now extends to additional steroid hormones, such as progesterone and pregnenolone. The U.S. EPA’s ToxCast program further advanced this method, enabling high-throughput measurement of 11 steroidogenesis-related hormones (Haggard et al., 2018). While the H295R assay indirectly reflects disruptions in overall steroidogenesis (e.g., changes in testosterone levels), it does not provide mechanistic insights.

Testosterone can be measured by immunoassays and by isotope-dilution gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in serum (Taieb et al., 2003; Paduch et al., 2014). Testosterone levels may also be measured by: Fish Lifecycle Toxicity Test (FLCTT) (US EPA OPPTS 850.1500), Male pubertal assay (PP Male Assay) (US EPA OPPTS 890.1500), OECD TG 441: Hershberger Bioassay in Rats (H Assay).

References

Baker, M.E. (2011). Insights from the structure of estrogen receptor into the evolution of estrogens: implications for endocrine disruption. Biochem Pharmacol, 82(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2011.03.008

Chandrashekar, V., & Bartke, A. (1998). The Role of Growth Hormone in the Control of Gonadotropin Secretion in Adult Male Rats*. Endocrinology, 139(3), 1067–1074. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.139.3.5816

Ellis, G. B., Desjardins, C., & Fraser, H. M. (1983). Control of Pulsatile LH Release in Male Rats. Neuroendocrinology, 37(3), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1159/000123540

Haggard, D. E., Karmaus, A. L., Martin, M. T., Judson, R. S., Setzer, R. W., & Paul Friedman, K. (2018). High-Throughput H295R Steroidogenesis Assay: Utility as an Alternative and a Statistical Approach to Characterize Effects on Steroidogenesis. Toxicological Sciences, 162(2), 509–534. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfx274

Heemers, H. V, Verhoeven, G., & Swinnen, J. V. (2006). Androgen activation of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein pathway: Current insights. Molecular Endocrinology (Baltimore, Md.), 20(10), 2265–77. doi:10.1210/me.2005-0479

Luetjens, C. M., & Weinbauer, G. F. (2012). Testosterone: biosynthesis, transport, metabolism and (non-genomic) actions. In Testosterone (pp. 15–32). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139003353.003

Murashima, A., Kishigami, S., Thomson, A., & Yamada, G. (2015). Androgens and mammalian male reproductive tract development. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1849(2), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.05.020

Naamneh Elzenaty, R., du Toit, T., & Flück, C. E. (2022). Basics of androgen synthesis and action. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 36(4), 101665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2022.101665

Paduch, D. A., Brannigan, R. E., Fuchs, E. F., Kim, E. D., Marmar, J. L., & Sandlow, J. I. (2014). The laboratory diagnosis of testosterone deficiency. Urology, 83(5), 980–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2013.12.024

Rey, R. A. (2021). The Role of Androgen Signaling in Male Sexual Development at Puberty. Endocrinology, 162(2). https://doi.org/10.1210/endocr/bqaa215

Shiraishi, S., Lee, P. W. N., Leung, A., Goh, V. H. H., Swerdloff, R. S., & Wang, C. (2008). Simultaneous Measurement of Serum Testosterone and Dihydrotestosterone by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Clinical Chemistry, 54(11), 1855–1863. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2008.103846

Taieb, J., Mathian, B., Millot, F., Patricot, M.-C., Mathieu, E., Queyrel, N., … Boudou, P. (2003). Testosterone measured by 10 immunoassays and by isotope-dilution gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in sera from 116 men, women, and children. Clinical Chemistry, 49(8), 1381–95.

Trost, L. W., & Mulhall, J. P. (2016). Challenges in Testosterone Measurement, Data Interpretation, and Methodological Appraisal of Interventional Trials. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(7), 1029–1046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.04.068

Vitousek, M. N., Johnson, M. A., Donald, J. W., Francis, C. D., Fuxjager, M. J., Goymann, W., Hau, M., Husak, J. F., Kircher, B. K., Knapp, R., Martin, L. B., Miller, E. T., Schoenle, L. A., Uehling, J. J., & Williams, T. D. (2018). HormoneBase, a population-level database of steroid hormone levels across vertebrates. Scientific Data, 5(1), 180097. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.97

Event: 1614: Decrease, androgen receptor activation

Short Name: Decrease, AR activation

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| androgen receptor activity | androgen receptor | decreased |

AOPs Including This Key Event

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Tissue |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mixed | High |

This KE is considered broadly applicable across mammalian taxa as all mammals express the AR in numerous cells and tissues where it regulates gene transcription required for developmental processes and functions. It is, however, acknowledged that this KE most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to add additional relevant knowledge to expand on the applicability to also include other vertebrates.

Key Event Description

This KE refers to decreased activation of the androgen receptor (AR) as occurring in complex biological systems such as tissues and organs in vivo. It is thus considered distinct from KEs describing either blocking of AR or decreased androgen synthesis.

The AR is a nuclear transcription factor with canonical AR activation regulated by the binding of the androgens such as testosterone or dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Thus, AR activity can be decreased by reduced levels of steroidal ligands (testosterone, DHT) or the presence of compounds interfering with ligand binding to the receptor (Davey & Grossmann, 2016; Gao et al., 2005).

In the inactive state, AR is sequestered in the cytoplasm of cells by molecular chaperones. In the classical (genomic) AR signaling pathway, AR activation causes dissociation of the chaperones, AR dimerization and translocation to the nucleus to modulate gene expression. AR binds to the androgen response element (ARE) (Davey & Grossmann, 2016; Gao et al., 2005). Notably, for transcriptional regulation the AR is closely associated with other co-factors that may differ between cells, tissues and life stages. In this way, the functional consequence of AR activation is cell- and tissue-specific. This dependency on co-factors such as the SRC proteins also means that stressors affecting recruitment of co-activators to AR can result in decreased AR activity (Heinlein & Chang, 2002).

Ligand-bound AR may also associate with cytoplasmic and membrane-bound proteins to initiate cytoplasmic signaling pathways with other functions than the nuclear pathway. Non-genomic AR signaling includes association with Src kinase to activate MAPK/ERK signaling and activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Decreased AR activity may therefore be a decrease in the genomic and/or non-genomic AR signaling pathways (Leung & Sadar, 2017).

How it is Measured or Detected

This KE specifically focuses on decreased in vivo activation, with most methods that can be used to measure AR activity carried out in vitro. They provide indirect information about the KE and are described in lower tier MIE/KEs (see for example MIE/KE-26 for AR antagonism, KE-1690 for decreased T levels and KE-1613 for decreased dihydrotestosterone levels). Assays may in the future be developed to measure AR activation in mammalian organisms.

References

Davey, R. A., & Grossmann, M. (2016). Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. The Clinical Biochemist. Reviews, 37(1), 3–15.

Gao, W., Bohl, C. E., & Dalton, J. T. (2005). Chemistry and structural biology of androgen receptor. Chemical Reviews, 105(9), 3352–3370. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020456u

Heinlein, C. A., & Chang, C. (2002). Androgen Receptor (AR) Coregulators: An Overview. https://academic.oup.com/edrv/article/23/2/175/2424160

Leung, J. K., & Sadar, M. D. (2017). Non-Genomic Actions of the Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00002

OECD (2022). Test No. 251: Rapid Androgen Disruption Activity Reporter (RADAR) assay. Paris: OECD Publishing doi:10.1787/da264d82-en.

|

|

|

Event: 286: Altered, Transcription of genes by the androgen receptor

Short Name: Altered, Transcription of genes by the AR

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| regulation of gene expression | androgen receptor | decreased |

AOPs Including This Key Event

Stressors

| Name |

|---|

| Bicalutamide |

| Cyproterone acetate |

| Epoxiconazole |

| Flutamide |

| Flusilazole |

| Prochloraz |

| Propiconazole |

| Stressor:286 Tebuconazole |

| Triticonazole |

| Vinclozalin |

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Tissue |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mixed | High |

Both the DNA-binding and ligand-binding domains of the AR are highly evolutionary conserved, whereas the transactivation domain show more divergence, which may affect AR-mediated gene regulation across species (Davey and Grossmann 2016). Despite certain inter-species differences, AR function mediated through gene expression is highly conserved, with mutation studies from both humans and rodents showing strong correlation for AR-dependent development and function (Walters et al. 2010).

This KE is considered broadly applicable across mammalian taxa, sex and developmental stages, as all mammals express the AR in numerous cells and tissues where it regulates gene transcription required for developmental processes and function. It is, however, acknowledged that this KE most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to add additional relevant knowledge to expand on the applicability to also include other vertebrates.

Key Event Description

This KE refers to transcription of genes by the androgen receptor (AR) as occurring in complex biological systems such as tissues and organs in vivo. Rather than measuring individual genes, this KE aims to capture patterns of effects at transcriptome level in specific target cells/tissues. In other words, it can be replaced by specific KEs for individual adverse outcomes as information becomes available, for example the transcriptional toxicity response in prostate tissue for AO: prostate cancer, perineum tissue for AO: reduced AGD, etc. AR regulates many genes that differ between tissues and life stages and, importantly, different gene transcripts within individual cells can go in either direction since AR can act as both transcriptional activator and suppressor. Thus, the ‘directionality’ of the KE cannot be either reduced or increased, but instead describe an altered transcriptome.

The Androgen Receptor and its function

The AR belongs to the steroid hormone nuclear receptor family. It is a ligand-activated transcription factor with three domains: the N-terminal domain, the DNA-binding domain, and the ligand-binding domain with the latter being the most evolutionary conserved (Davey and Grossmann 2016). Androgens (such as dihydrotestosterone and testosterone) are AR ligands and act by binding to the AR in androgen-responsive tissues (Davey and Grossmann 2016). Human AR mutations and mouse knockout models have established a fundamental role for AR in masculinization and spermatogenesis (Maclean et al.; Walters et al. 2010; Rana et al. 2014). The AR is also expressed in many other tissues such as bone, muscles, ovaries and within the immune system (Rana et al. 2014).

Altered transcription of genes by the AR as a Key Event

Upon activation by ligand-binding, the AR translocates from the cytoplasm to the cell nucleus, dimerizes, binds to androgen response elements in the DNA to modulate gene transcription (Davey and Grossmann 2016). The transcriptional targets vary between cells and tissues, as well as with developmental stages and is also dependent on available co-regulators (Bevan and Parker 1999; Heemers and Tindall 2007). It should also be mentioned that the AR can work in other ‘non-canonial’ ways such as non-genomic signaling, and ligand-independent activation (Davey & Grossmann, 2016; Estrada et al, 2003; Jin et al, 2013).

A large number of known, and proposed, target genes of AR canonical signaling have been identified by analysis of gene expression following treatments with AR agonists (Bolton et al. 2007; Ngan et al. 2009, Jin et al. 2013).

How it is Measured or Detected

Altered transcription of genes by the AR can be measured by measuring the transcription level of known downstream target genes by RT-qPCR or other transcription analyses approaches, e.g. transcriptomics.

Since this KE aims to capture AR-mediated transcriptional patterns of effect, downstream bioinformatics analyses will typically be required to identify and compare effect footprints. Clusters of genes can be statistically associated with, for example, biological process terms or gene ontology terms relevant for AR-mediated signaling. Large transcriptomics data repositories can be used to compare transcriptional patterns between chemicals, tissues, and species (e.g. TOXsIgN (Darde et al, 2018a; Darde et al, 2018b), comparisons can be made to identified sets of AR ‘biomarker’ genes (e.g. as done in (Rooney et al, 2018)), and various methods can be used e.g. connectivity mapping (Keenan et al, 2019).

References

Bevan C, Parker M (1999) The role of coactivators in steroid hormone action. Exp. Cell Res. 253:349–356

Bolton EC, So AY, Chaivorapol C, et al (2007) Cell- and gene-specific regulation of primary target genes by the androgen receptor. Genes Dev 21:2005–2017. doi: 10.1101/gad.1564207

Darde, T. A., Gaudriault, P., Beranger, R., Lancien, C., Caillarec-Joly, A., Sallou, O., et al. (2018a). TOXsIgN: a cross-species repository for toxicogenomic signatures. Bioinformatics 34, 2116–2122. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty040.

Darde, T. A., Chalmel, F., and Svingen, T. (2018b). Exploiting advances in transcriptomics to improve on human-relevant toxicology. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 11–12, 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.cotox.2019.02.001.

Davey RA, Grossmann M (2016) Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. Clin Biochem Rev 37:3–15

Estrada M, Espinosa A, Müller M, Jaimovich E (2003) Testosterone Stimulates Intracellular Calcium Release and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases Via a G Protein-Coupled Receptor in Skeletal Muscle Cells. Endocrinology 144:3586–3597. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0164

Heemers H V., Tindall DJ (2007) Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: A diversity of functions converging on and regulating the AR transcriptional complex. Endocr. Rev. 28:778–808

Jin, Hong Jian, Jung Kim, and Jindan Yu. 2013. “Androgen Receptor Genomic Regulation.” Translational Andrology and Urology 2(3):158–77. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2013.09.01

Keenan, A. B., Wojciechowicz, M. L., Wang, Z., Jagodnik, K. M., Jenkins, S. L., Lachmann, A., et al. (2019). Connectivity Mapping: Methods and Applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2, 69–92. doi:10.1146/ANNUREV-BIODATASCI-072018-021211.

Maclean HE, Chu S, Warne GL, Zajact JD Related Individuals with Different Androgen Receptor Gene Deletions

MacLeod DJ, Sharpe RM, Welsh M, et al (2010) Androgen action in the masculinization programming window and development of male reproductive organs. In: International Journal of Andrology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp 279–287

Ngan S, Stronach EA, Photiou A, et al (2009) Microarray coupled to quantitative RT–PCR analysis of androgen-regulated genes in human LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 28:2051–2063. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.68

Rana K, Davey RA, Zajac JD (2014) Human androgen deficiency: Insights gained from androgen receptor knockout mouse models. Asian J. Androl. 16:169–177

Rooney, J. P., Chorley, B., Kleinstreuer, N., and Corton, J. C. (2018). Identification of Androgen Receptor Modulators in a Prostate Cancer Cell Line Microarray Compendium. Toxicol. Sci. 166, 146–162. doi:10.1093/TOXSCI/KFY187.

Walters KA, Simanainen U, Handelsman DJ (2010) Molecular insights into androgen actions in male and female reproductive function from androgen receptor knockout models. Hum Reprod Update 16:543–558. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq003

List of Adverse Outcomes in this AOP

Event: 2082: Hypospadias, increased

Short Name: Hypospadias

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| embryonic organ development | penis | abnormal |

AOPs Including This Key Event

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Organ |

Organ term

| Organ term |

|---|

| penis |

Domain of Applicability

Taxonomic Applicability| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| human | Homo sapiens | High | NCBI |

| mouse | Mus musculus | High | NCBI |

| rat | Rattus norvegicus | High | NCBI |

| mammals | mammals | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Perinatal | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

Taxonomic applicability: Numerous studies have shown an association in humans between in utero exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals and hypospadias. In mice and rats, in utero exposure to several endocrine disrupting chemicals, in particular estrogens and antiandrogens, have been shown to cause hypospadias in male offspring at different frequencies (Mattiske & Pask, 2021). Androgen-driven development of the male external genitalia is evolutionary conserved in most mammals and, to some extent, also in other vertebrate classes (Gredler et al., 2014). Hypospadias can in principle occur in all animals that form a genital tubercle and have been observed in many domestic animal species and wildlife species.

Life stage applicability: Penis development is finished prenatally in humans, and hypospadias is diagnosed at birth (Baskin & Ebbers, 2006). In rodents, penis development is not fully completed until weeks after birth, but hypospadias may be identified in early postnatal life as well, and in some cases in late gestation (Sinclair et al., 2017).

Sex applicability: Hypospadias is primarily used in reference to malformation of the male external genitalia.

Key Event Description

Hypospadias is a malformation of the penis where the urethral opening is displaced from the tip of the glans, usually on the ventral side on the phallus. Most cases of hypospadias are milder where the urethral opening still appears on the glans proper or on the most distal part of the shaft. In more severe cases, the opening may be more proximally placed on the shaft or even as low as the scrotum or the perineum.

In addition to the misplacement of the urethral opening, hypospadias is associated with an absence of ventral prepuce, an excess of dorsal preputial tissue, and in some cases a downward curvature of the penis (chordee). Patients with hypospadias may need surgical repairment depending on severity, with more proximal hypospadias patients in most need of surgeries to achieve optimal functional and cosmetic results (Baskin, 2000; Baskin & Ebbers, 2006; Mattiske & Pask, 2021). The incidence of hypospadias varies greatly between countries, from 1:100 to 1:500 of newborn boys (Skakkebaek et al., 2016), and the global prevalence seems to be increasing (Paulozzi, 1999; Springer et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2019).

The external genitalia arise from the biphasic genital tubercle during fetal development. Androgens (testosterone and dihydrotestosterone) drive formation of the male external genitalia. In humans, the urethra develops by fusion of two endoderm-derived urethral folds. Disruption of genital tubercle differentiation results in an incomplete urethra, i.e. hypospadias. (Baskin, 2000; Baskin & Ebbers, 2006).

How it is Measured or Detected

In humans, hypospadias is diagnosed clinically by physical examination of the infant and is at first recognized by the absence of ventral prepuce and concurrent excess dorsal prepuce (Baskin, 2000). Hypospadias may be classified according to the location of the urethral meatus: Glandular, subcoronal, midshaft, penoscrotal, scrotal, and perineal (Baskin & Ebbers, 2006).

In mice and rats, macroscopic assessment of hypospadias may be performed postnatally, and several OECD test guidelines require macroscopic examination of genital abnormalities in in vivo toxicity studies (TG 414, 416, 421/422, 443). The guidelines do not define hypospadias or how to identify them. Fetal and neonatal identification of hypospadias may require microscopic examination for proper evaluation of the pathology. This can be done by scanning electron microscopy (Uda et al., 2004), or by histological assessment in which the presence of the urethral opening in proximal, transverse sections (for example co-occuring with the os penis or corpus cavernosum), indicates hypospadias (Mahawong et al., 2014; Sinclair et al., 2017; Vilela et al., 2007). In a semiquantitative, histologic approach, the number of transverse sections of the penis with internalization of the urethra was related to the total length of the penis, achieving a percentage of urethral internalization. In this study, ≤89% of urethral internalization was defined as indicative of mild hypospadias (Stewart et al., 2018).

Regulatory Significance of the AO

In the OECD guidelines for developmental and reproductive toxicology, several test endpoints include examination of structural abnormalities with special attention to the organs of the reproductive system. These are: Test No. 414 ‘Prenatal Developmental Toxicity Study’ (OECD, 2018a); Test No. 416 ‘Two-Generation Reproduction Toxicity’ (OECD, 2001) and Tests No. 421/422 ‘Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test’ (OECD, 2016a, 2016b). In Test No. 443 ‘Extended One-Generation Reproductive Toxicity Study’ (OECD, 2018b), hypospadias is specifically mentioned as a genital abnormality to note.

References

Baskin, L. S. (2000). Hypospadias and urethral development. The Journal of Urology, 163(3), 951–956.

Baskin, L. S., & Ebbers, M. B. (2006). Hypospadias: Anatomy, etiology, and technique. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 41(3), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.059

Gredler, M. L., Larkins, C. E., Leal, F., Lewis, A. K., Herrera, A. M., Perriton, C. L., Sanger, T. J., & Cohn, M. J. (2014). Evolution of External Genitalia: Insights from Reptilian Development. Sexual Development, 8(5), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1159/000365771

Mahawong, P., Sinclair, A., Li, Y., Schlomer, B., Rodriguez, E., Ferretti, M. M., Liu, B., Baskin, L. S., & Cunha, G. R. (2014). Prenatal diethylstilbestrol induces malformation of the external genitalia of male and female mice and persistent second-generation developmental abnormalities of the external genitalia in two mouse strains. Differentiation, 88(2–3), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2014.09.005

Mattiske, D. M., & Pask, A. J. (2021). Endocrine disrupting chemicals in the pathogenesis of hypospadias; developmental and toxicological perspectives. Current Research in Toxicology, 2, 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2021.03.004

OECD. (2001). Test No. 416: Two-Generation Reproduction Toxicity. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264070868-en

OECD. (2018). Test No. 414: Prenatal Developmental Toxicity Study. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264070820-en

OECD. (2025a). Test No. 421: Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1787/9789264264380-en

OECD. (2025b). Test No. 422: Combined Repeated Dose Toxicity Study with the Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Test. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4. OECD Publising. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1787/9789264264403-en

OECD. (2025c). Test No. 443: Extended One-Generation Reproductive Toxicity Study. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1787/9789264185371-en

Paulozzi, L. J. (1999). International Trends in Rates of Hypospadias and Cryptorchidism. Environmental Health Perspectives, 107(4), 297–302. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.99107297

Sinclair, A. W., Cao, M., Pask, A., Baskin, L., & Cunha, G. R. (2017). Flutamide-induced hypospadias in rats: A critical assessment. Differentiation, 94, 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2016.12.001

Skakkebaek, N. E., Rajpert-De Meyts, E., Buck Louis, G. M., Toppari, J., Andersson, A.-M., Eisenberg, M. L., Jensen, T. K., Jørgensen, N., Swan, S. H., Sapra, K. J., Ziebe, S., Priskorn, L., & Juul, A. (2016). Male Reproductive Disorders and Fertility Trends: Influences of Environment and Genetic Susceptibility. Physiological Reviews, 96(1), 55–97. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00017.2015.-It

Springer, A., van den Heijkant, M., & Baumann, S. (2016). Worldwide prevalence of hypospadias. Journal of Pediatric Urology, 12(3), 152.e1-152.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.12.002

Stewart, M. K., Mattiske, D. M., & Pask, A. J. (2018). In utero exposure to both high- and low-dose diethylstilbestrol disrupts mouse genital tubercle development. Biology of Reproduction, 99(6), 1184–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioy142

Uda, A., Kojima, Y., Hayashi, Y., Mizuno, K., Asai, N., & Kohri, K. (2004). Morphological features of external genitalia in hypospadiac rat model: 3-dimensional analysis. The Journal of Urology, 171(3), 1362–1366. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JU.0000100140.42618.54

Vilela, M. L. B., Willingham, E., Buckley, J., Liu, B. C., Agras, K., Shiroyanagi, Y., & Baskin, L. S. (2007). Endocrine Disruptors and Hypospadias: Role of Genistein and the Fungicide Vinclozolin. Urology, 70(3), 618–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2007.05.004

Yu, X., Nassar, N., Mastroiacovo, P., Canfield, M., Groisman, B., Bermejo-Sánchez, E., Ritvanen, A., Kiuru-Kuhlefelt, S., Benavides, A., Sipek, A., Pierini, A., Bianchi, F., Källén, K., Gatt, M., Morgan, M., Tucker, D., Canessa, M. A., Gajardo, R., Mutchinick, O. M., … Agopian, A. J. (2019). Hypospadias Prevalence and Trends in International Birth Defect Surveillance Systems, 1980–2010. European Urology, 76(4), 482–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2019.06.027

Appendix 2

List of Key Event Relationships in the AOP

List of Adjacent Key Event Relationships

Relationship: 3448: Decrease, intratesticular testosterone leads to Decrease, circulating testosterone levels

AOPs Referencing Relationship

| AOP Name | Adjacency | Weight of Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased testosterone synthesis leading to short anogenital distance (AGD) in male (mammalian) offspring | adjacent | High | Moderate |

| Decreased testosterone synthesis leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring | adjacent | High | |

| Decreased testosterone synthesis leading to increased nipple retention (NR) in male (rodent) offspring | adjacent | High |

Evidence Supporting Applicability of this Relationship

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| All life stages | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

Taxonomic applicability

The KER is assessed applicable to mammals, as testicular testosterone synthesis is common for all mammals. It is, however, acknowledged that this KER most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates.

Sex applicability

This KER is only applicable to males, as testes are only found in males.

Life stage applicability

This KER is applicable to all life stages. Once formed, the testes produce and secrete testosterone during fetal development and throughout postnatal life, although testosterone levels do vary between life stages (Vesper et al., 2015).

Key Event Relationship Description

This KE describes a decrease in intratesticular testosterone production leading to a decrease in circulating levels of testosterone. Intratesticular testosterone can be measured in whole testicular tissue samples by testing ex vivo testicular testosterone production, and circulating testosterone is measured in plasma or serum. In males, the testes produce and secrete the majority of the circulating testosterone, with only a small contribution from the adrenal gland (Naamneh Elzenaty et al., 2022). In mammals, intratesticular testosterone levels are 30- to 100-fold higher than serum testosterone levels (Coviello et al., 2004; McLachlan et al., 2002; Turner et al., 1984). Reducing testicular testosterone will consequently lead to a reduction in circulating levels as well.

Evidence Supporting this KER

Biological PlausibilityThe biological plausibility for this KER is considered high. The testes are the primary testosterone-producing organs in male mammals and the main contributors to the circulating testosterone levels in males (Naamneh Elzenaty et al., 2022). A decrease in intratesticular testosterone will therefore lead to a decrease in secretion of testosterone and consequently lower circulating levels of testosterone.

Empirical EvidenceThe empirical evidence for this KER is overall judged as high.

In vivo toxicity studies in rats and mice have shown that exposure to substances that lowers intratesticular testosterone also lowers circulating testosterone levels. This includes in utero exposure and measurements in fetal males (Borch J et al., 2004; Vinggaard AM et al., 2005) as well as exposure and measurements postnatally in male rodents (Hou X et al., 2020; Ji et al., 2010; Jiang XP et al., 2017)

Supporting this evidence are castration studies in male rats and monkeys, showing a marked reduction in circulating testosterone levels when removing the testes (Gomes & Jain, 1976; Perachio et al., 1977).

Lastly, in humans, males with hypogonadism or gonadal dysgenesis present with lower circulating testosterone levels (Hirose Y et al., 2007; Jones LW et al., 1970).

Dose concordance

In vivo toxicity studies support dose concordance for this KER, as exemplified below.

In pre-pubertal/pubertal male rats, chlorocholine chloride exposure (postnatal day (PND) 23-60) in three doses reduced both intratesticular and serum testosterone levels at PND60 at all doses tested (Hou X et al., 2020).

Perinatal exposure (gestational day (GD) 10-birth) of male mice to diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) in three doses (100, 500, and 1000 mg/kg bw/day) reduced intratesticular testosterone at 500 and 1000 mg/kg bw/day at PND1, while only 1000 mg/kg bw/day reduced serum levels of testosterone, although this was measured later, at PND56 (Xie Q et al., 2024)

In utero exposure (GD7-21) of male rats to DEHP in doses of 300 or 750 mg/kg bw/day reduced intratesticular testosterone levels at GD21, while only the high dose also reduced plasma testosterone levels (Borch J et al., 2004).

Temporal concordance

In vivo toxicity studies moderately support temporal concordance for this KER, as exemplified below.

Several studies show that a decrease in intratesticular and circulating testosterone can be measured at the same time point (Borch J et al., 2004; Hou X et al., 2020; Jiang XP et al., 2017; Vinggaard AM et al., 2005).

In utero exposure of male mice to DEHP from GD10 to birth reduced intratesticular testosterone levels at PND1 with LOAEL 500 mg/kg bw/day, and when measured at PND56, circulating testosterone levels were decreased, but with LOAEL 1000 mg/kg bw/day (Xie Q et al., 2024).

In Fisher JS et al., 2003, exposure of male rats from GD13-21 to 500 mg/kg bw/day dibutyl phthalate reduced intratesticular testosterone by ~90% (measured at GD19). When analyzing circulating testosterone levels at PND4, 10, 15, 25, and 90, only the testosterone levels on PND25 were decreased.

One study report conflicting results on the temporal concordance of this KER (Caceres et al., 2023). Here, male rats were exposed for 20 weeks from PND60 to a mixture of the phytoestrogens genistein and daidzein (combined dose of either 29 or 290 mg/kg bw/day). Intratesticular testosterone was measured every 4 weeks, while serum levels of testosterone were measured every second week. While the mixture caused a reduction of serum testosterone after 2 weeks of exposure, a reduction in intratesticular testosterone was not measured until after 8 weeks. The discrepancy might be explained by the multiple mechanisms of action of the phytoestrogens, as they, besides affecting testicular testosterone synthesis, may also influence peripheral aromatization of testosterone to estrogens (van Duursen et al., 2011).

Incidence concordance

Incidence concordance can not be evaluated for this KER.

Uncertainties and InconsistenciesThere are examples of in vivo studies, in which stressors exposure have caused a reduction in intratesticular testosterone levels without a reduction in circulating testosterone levels.

Quantitative Understanding of the Linkage

Time-scaleThe time-scale for this KER is likely minutes or hours, as testosterone is secreted into the blood from the testes after synthesis. In vivo, a decrease in intratesticular and circulating testosterone can be measured at the same time, both in fetal and postnatal studies (Borch J et al., 2004; Hou X et al., 2020; Jiang XP et al., 2017; Vinggaard AM et al., 2005). Ex vivo, chemically-induced reduction in testicular production of testosterone can be measured in culture media after 3 hours incubation (earlier time points were not measured) (Wilson et al., 2009).

Known Feedforward/Feedback loops influencing this KERTestosterone is a part of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which controls testosterone synthesis in puberty and adulthood. In this axis, gonatropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released from the hypothalamus and stimulates release of luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary. LH acts on the testes to produce and secrete testosterone. Elevated circulating testosterone levels exerts negative feedback on the HPG axis (decreasing GnRH secretion) to keep testosterone levels in balance (Tilbrook & Clarke, 2001).

Importantly, there are species-specific differences in when the HPG axis is functional during development. In the mouse, fetal testosterone synthesis is independent of pituitary LH (O’Shaughnessy et al., 1998), whereas in humans, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) act similarly to LH and appear to be critical in stimulating testosterone synthesis in the fetal testis (Huhtaniemi, 2025).

References

Borch J, Ladefoged O, Hass U, & Vinggaard AM. (2004). Steroidogenesis in fetal male rats is reduced by DEHP and DINP, but endocrine effects of DEHP are not modulated by DEHA in fetal, prepubertal and adult male rats. Reproductive Toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.), 18(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2003.10.011

Caceres, S., Crespo, B., Alonso-Diez, A., De Andrés, P. J., Millan, P., Silván, G., Illera, M. J., & Illera, J. C. (2023). Long-Term Exposure to Isoflavones Alters the Hormonal Steroid Homeostasis-Impairing Reproductive Function in Adult Male Wistar Rats. Nutrients, 15(5), 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051261

Coviello, A. D., Bremner, W. J., Matsumoto, A. M., Herbst, K. L., Amory, J. K., Anawalt, B. D., Yan, X., Brown, T. R., Wright, W. W., Zirkin, B. R., & Jarow, J. P. (2004). Intratesticular Testosterone Concentrations Comparable With Serum Levels Are Not Sufficient to Maintain Normal Sperm Production in Men Receiving a Hormonal Contraceptive Regimen. Journal of Andrology, 25(6), 931–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb03164.x

Fisher JS, Macpherson S, Marchetti N, & Sharpe RM. (2003). Human “testicular dysgenesis syndrome”: A possible model using in-utero exposure of the rat to dibutyl phthalate. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 18(7), 1383–1394. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deg273

Gomes, W. R., & Jain, S. K. (1976). Effect of unilateral and bilateral castration and cryptorchidism on serum gonadotrophins in the rat. The Journal of Endocrinology, 68(02), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.0.0680191

Hirose Y, Sasa M, Bando Y, Hirose T, Morimoto T, Kurokawa Y, Nagao T, & Tangoku A. (2007). Bilateral male breast cancer with male potential hypogonadism. World Journal of Surgical Oncology, 5, 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-5-60

Hou X, Hu H, Xiagedeer B, Wang P, Kang C, Zhang Q, Meng Q, & Hao W. (2020). Effects of chlorocholine chloride on pubertal development and reproductive functions in male rats. Toxicology Letters, 319, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2019.10.024

Huhtaniemi, I. T. (2025). Luteinizing hormone receptor knockout mouse: What has it taught us? Andrology, andr.70000. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.70000

Ji, Y.-L., Wang, H., Liu, P., Wang, Q., Zhao, X.-F., Meng, X.-H., Yu, T., Zhang, H., Zhang, C., Zhang, Y., & Xu, D.-X. (2010). Pubertal cadmium exposure impairs testicular development and spermatogenesis via disrupting testicular testosterone synthesis in adult mice. Reproductive Toxicology, 29(2), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.10.014

Jiang XP, Tang JY, Xu Z, Han P, Qin ZQ, Yang CD, Wang SQ, Tang M, Wang W, Qin C, Xu Y, Shen BX, Zhou WM, & Zhang W. (2017). Sulforaphane attenuates di-N-butylphthalate-induced reproductive damage in pubertal mice: Involvement of the Nrf2-antioxidant system. Environmental Toxicology, 32(7), 1908–1917. https://doi.org/10.1002/tox.22413

Jones LW, Isaacs H Jr, Edelbrock H, & Donnell GN. (1970). Reifenstein’s syndrome: Hereditary familial hypogonadism with hypospadias and gynecomastia. The Journal of Urology, 104(4), 608–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(17)61793-2

McLachlan, R. I., O’Donnell, L., Stanton, P. G., Balourdos, G., Frydenberg, M., de Kretser, D. M., & Robertson, D. M. (2002). Effects of Testosterone Plus Medroxyprogesterone Acetate on Semen Quality, Reproductive Hormones, and Germ Cell Populations in Normal Young Men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 87(2), 546–556. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.87.2.8231

Naamneh Elzenaty, R., Du Toit, T., & Flück, C. E. (2022). Basics of androgen synthesis and action. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 36(4), 101665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2022.101665

O’Shaughnessy, P. J., Baker, P., Sohnius, U., Haavisto, A.-M., Charlton, H. M., & Huhtaniemi, I. (1998). Fetal Development of Leydig Cell Activity in the Mouse Is Independent of Pituitary Gonadotroph Function*. Endocrinology, 139(3), 1141–1146. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.139.3.5788

Perachio, A. A., Alexander, M., Marr, L. D., & Collins, D. C. (1977). Diurnal variations of serum testosterone levels in intact and gonadectomized male and female rhesus monkeys. Steroids, 29(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-128X(77)90106-4

Tilbrook, A. J., & Clarke, I. J. (2001). Negative Feedback Regulation of the Secretion and Actions of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone in Males. Biology of Reproduction, 64(3), 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod64.3.735

Turner, T. T., Jones, C. E., Howards, S. S., Ewing, L. L., Zegeye, B., & Gunsalus, G. L. (1984). On the androgen microenvironment of maturing spermatozoa. Endocrinology, 115(5), 1925–1932. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-115-5-1925

van Duursen, M. B. M., Nijmeijer, S. M., de Morree, E. S., de Jong, P. Chr., & van den Berg, M. (2011). Genistein induces breast cancer-associated aromatase and stimulates estrogen-dependent tumor cell growth in in vitro breast cancer model. Toxicology, 289(2), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2011.07.005

Vesper, H. W., Wang, Y., Vidal, M., Botelho, J. C., & Caudill, S. P. (2015). Serum Total Testosterone Concentrations in the US Household Population from the NHANES 2011-2012 Study Population. Clinical Chemisty, 61(12), 1495–1504. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2015.245969

Vinggaard AM, Christiansen S, Laier P, Poulsen ME, Breinholt V, Jarfelt K, Jacobsen H, Dalgaard M, Nellemann C, & Hass U. (2005). Perinatal exposure to the fungicide prochloraz feminizes the male rat offspring. Toxicological Sciences : An Official Journal of the Society of Toxicology, 85(2), 886–897. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfi150

Wilson, V. S., Lambright, C. R., Furr, J. R., Howdeshell, K. L., & Gray, L. E., Jr. (2009). The herbicide linuron reduces testosterone production from the fetal rat testis during both in utero and in vitro exposures. TOXICOLOGY LETTERS, 186(2), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.12.017

Xie Q, Cao H, Liu H, Xia K, Gao Y, & Deng C. (2024). Prenatal DEHP exposure induces lifelong testicular toxicity by continuously interfering with steroidogenic gene expression. Translational Andrology and Urology, 13(3), 369–382. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau-23-503

Relationship: 2131: Decrease, circulating testosterone levels leads to Decrease, AR activation

AOPs Referencing Relationship

| AOP Name | Adjacency | Weight of Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of 17α-hydrolase/C 10,20-lyase (Cyp17A1) activity leads to birth reproductive defects (cryptorchidism) in male (mammals) | adjacent | High | High |

| Decreased testosterone synthesis leading to short anogenital distance (AGD) in male (mammalian) offspring | adjacent | High | Moderate |

| Decreased testosterone synthesis leading to hypospadias in male (mammalian) offspring | adjacent | High | |

| Decreased testosterone synthesis leading to increased nipple retention (NR) in male (rodent) offspring | adjacent | High |

Evidence Supporting Applicability of this Relationship

| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| mammals | mammals | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| During development and at adulthood | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mixed | High |

Taxonomic applicability

KER2131 is assessed applicable to mammals, as T and AR activation are known to be related in mammals. It is, however, acknowledged that this KER most likely has a much broader domain of applicability extending to non-mammalian vertebrates. AOP developers are encouraged to add additional relevant knowledge to expand on the applicability to also include other vertebrates.

Sex applicability

KER2131 is assessed applicable to both sexes, as T activates AR in both males and females.

Life-stage applicability

KER2131 is considered applicable to developmental and adult life stages, as T-mediated AR activation is relevant from the AR is expressed.

Key Event Relationship Description

This key event relationship links decreased testosterone (T) levels to decreased androgen receptor (AR) activation. T is an endogenous steroid hormone important for, amongst other things, reproductive organ development and growth as well as muscle mass and spermatogenesis (Marks, 2004).T is, together with dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a primary ligand for the AR in mammals (Schuppe et al., 2020). Besides its genomic actions, the AR can also mediate rapid, non-genomic second messenger signaling (Davey & Grossmann, 2016). When T levels are reduced, less substrate is available for the AR, and hence, AR activation is decreased (Gao et al., 2005).

Evidence Supporting this KER

Biological PlausibilityThe biological plausibility for this KER is considered high